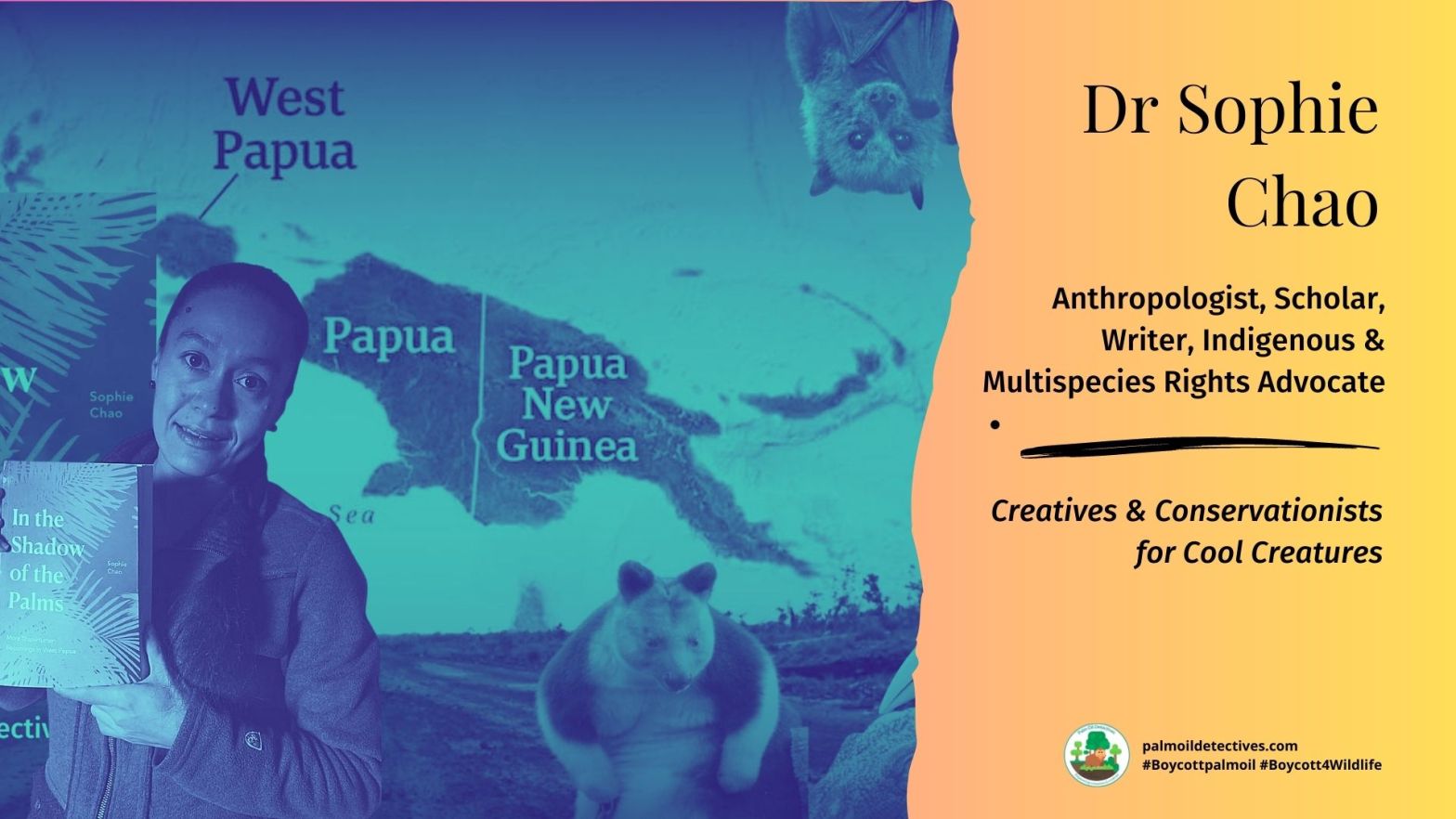

Dr Sophie Chao: In Her Own Words

Anthropologist, Scholar, Writer, Indigenous & Multispecies Rights Advocate

Bio: Dr Sophie Chao

Dr Sophie Chao is an environmental anthropologist and environmental humanities scholar interested in the intersections of capitalism, ecology, Indigeneity, health, and justice in the Pacific.

Her theoretical thinking is inspired by interdisciplinary currents including Science and Technology Studies, political ecology, and Indigenous, Postcolonial, and Critical Race Studies.

Dr Chao is currently a Discovery Early Career Research Award (DECRA) Fellow and Lecturer in Anthropology at the University of Sydney. Prior to her academic career, she worked for the international Indigenous rights organisation Forest Peoples Programme in the United Kingdom and Indonesia.

She has also undertaken consultancies for the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation and the United Nations Working Group on the Issue of Human Rights and Transnational Corporations. She is currently Secretary on the Executive Committee of the Australian Anthropological Society (AAS) and Co-Convenor of the Australian Food, Society, and Culture Network (AFSCN).

In 2022, Dr Chao released her much anticipated book In the Shadow of the Palms: More-Than-Human Becomings in West Papua, which examines the multispecies entanglements of oil palm plantations in West Papua, showing how Indigenous Marind communities understand and navigate the social, political, and environmental demands of palm oil. Her book won the inaugural Duke University Press Scholars of Colour First Book Award.

Dr Chao is keen to forge meaningful collaborations and conversations with Indigenous and decolonial academics, artists, and activists in Australia and beyond, and to move towards a better understanding of morethanhuman worlds.

Palm Oil Detectives is honoured to interview to Dr Sophie Chao about her research into the impacts of palm oil on the daily lives of Marind people and other sentient beings in West Papua.

“I want the world to understand how #deforestation and industrial #palmoil expansion undermine #Indigenous ways of being in #WestPapua” ~ Dr Sophie Chao #PapuanLivesMatter #Together4Forests #Boycott4Wildlife

Tweet

“#Indigenous #Marind of #WestPapua consider plants and animals NOT as passive objects of exploitation, but as other-than-human relatives. Subjects of #interspecies #justice in their own right” ~ Dr Sophie Chao #Boycott4Wildlife

Tweet

“I want to see the #palmoil industry/governments try to understand the desires of #Papuan people THEMSELVES instead of pre-conceived notions of what counts as progress” ~ Dr Sophie Chao #PapuanLivesMatter #Together4Forests

Tweet

“#Governments/ #corporates must accept that some #Indigenous communities may decide to withhold consent to #palmoil projects. Their right to say NO MUST be respected” ~ Dr Sophie Chao #PapuanLivesMatter #Boycott4Wildlife

Tweet

Little previous research had been done into how indigenous peoples themselves experience, interpret, and contest oil palm developments.

In particular, there is not much research done into how indigenous peoples relate to vulnerable, non-human beings such as native plants, animals, and elements, with whom many indigenous peoples entertain intimate and ancestral relations of kinship and care.

“Many people know that oil palm is devastating on tropical ecosystems and biodiversity. Much less is known about the impacts of this proliferating cash crop on the peoples who are being displaced, dispossessed, and disempowered in its wake.”

Pictured: A group of Marind women preparing sago starch that has been freshly rasped from the sago grove. Photo: Dr Sophie Chao

I wrote this book because I wanted the world to understand how deforestation and industrial oil palm expansion are undermining Indigenous ways of being in West Papua.

My book seeks to bring to life the worlds of people who live in the teeth of settler-colonial capitalism

[Pictured] Dr Sophie Chao

Living with Marind transformed how I think about what it means to be “human”

And also what it means to coexist in mutually beneficial ways with other-than-human beings.

The Marind think of plants and animals as not simply passive objects of human exploitation

Instead, these other-than-human beings are considered to be agents, persons, relatives, and subjects of justice in their own right.

This was a completely different way of thinking to the anthropocentric and individualistic logic of the Westernised parts of the world where I had lived, studied, and worked.

Indigenous Marind enriched my world by inviting me to think beyond nature-culture divides

Humans share the planet with a whole array of different creatures. These creatures matter in the making of more sustainable, collective futures.

“More-than-human becomings” is in the subtitle of the book because it is an invitation to think beyond the human and also beyond categories. Instead, the reader is invited to think about non-human beings and transforming worlds.

Marind are “More-than-human” because they consider themselves as beings within a lively and diverse ecology of life

This includes native plants and animals like cassowaries, birds of paradise, and sago palms, but also introduced – and sometimes dangerous – organisms like industrial oil palm.

“Becomings” was a way of getting readers to think about life beyond the static notion of “being.” To “become” is a constant transformation, unfolding differently across bodies, places, and time. Becoming, in some ways, never really ends.

The ‘good life’, according to Marind, stems from the willingness of humans to consider non-human beings as subjects of dignity and justice

This good life is best achieved by immersing oneself in the more-than-human environment. Non-human beings are considered to be participants in the making of shared worlds, and also as subjects of harm and violence.

The “good life” is deeply intergenerational for Marind. They often talked about nurturing the forest, as a way of becoming good ancestors and how they can transmit traditional ecological knowledge to future Marind generations

Time for Marind is not linear, it is spiralic

What you do now matters in terms of how you will be remembered. What you do now matters in terms of what you will be able to pass on to human and other-than-human beings to come.

There is a wisdom and responsibility that comes with this sense of time that I think is critical to heed in this age of planetary destruction.

Many of my Marind companions talk about conservation and capitalism as being “two sides of the same coin”

This is because they now find themselves excluded from both industrial oil palm plantations and from the conservation areas that are intended to off-set deforestation.

Images: Palm oil plantations and environmental destruction, Getty Images.

Both of these activities entrench a nature-culture divide that is alien to many Marind. Both undervalue the fact that Marind have always coexisted harmoniously with their environments.

These new “conservation zones” are the very same places where Marind fish, forage, and hunt. It is where they go to visit ancestral graveyards and sacred sites. It is where they walk with their families and friends to encounter their kindred sago palms, wild boards, possums, and gaharu trees.

For Marind, conservation and capitalism violate their territorial sovereignty and access to food and resources. Both types of activity are imposed by outside actors through top-down decision-making process that they are not party to.

Human rights and environmental abuses in West Papua are made invisible in Australia, their closest neighbour, mainly for geopolitical reasons

Racism may have something to do with it – but I think geopolitical interests are a big part of the story

West Papua is incredibly rich in natural resources – from gold, copper, and coal, to timber and oil palm. Economic and political interests tend to trump human and environmental rights, in West Papua and elsewhere.

There are pockets of activism and advocacy in Australia, including by West Papuan diaspora and political exiles – but the movement hasn’t caught the public’s attention in the way other political causes have.

Accessing West Papua is difficult for non-Indonesian individuals and organisations. There is heightened militarisation of the region. This contributes to an ongoing invisibilisation of what is happening at the ground level, among Papuan people and across Papuan ecosystems.

The demilitarisation of West Papua is absolutely vital if Papuans are to feel that they have a free voice in matters affecting them and their lands – including oil palm developments

Image: Andrew Gal for Getty Images

Indigenous ways of being and thinking (although radically different from neoliberal capitalist and colonialist logics), should be central to decision-making

I would like to see the palm oil industry, together with the Indonesian government, try to understand the views, aspirations, desires, beliefs, and hopes of Papuan peoples themselves instead of entering with pre-conceived notions of what counts as progress, the good life, and wellbeing.

Government and corporate actors should engaging with Indigenous Papuans through a transparent, iterative, and trust-based process of consent-seeking, before any oil palm projects are designed or implemented.

This consent should be sought freely, well ahead of time, and only when communities have been given access to comprehensive and impartial information on the benefits and risks of oil palm developments.

Pictured: Marind man and child in Merauke by Nanang Sujana

Most importantly, government and corporate actors need to accept that some communities may, following lengthy consultations, still decide to withhold their consent to oil palm projects. This right to say NO to oil palm must imperatively be respected.

Violence as a multispecies act: Marind describe oil palm as a colonising, killing and occupying plant beings

Oil palm, they often told me, does not want to share time and space with native plants, people, and animals.

It spreads uniformly across vast swaths of land, yet grows alone in monocrop form

This plant’s introduction has been accompanied by intensified military and corporate surveillance, community harassment and intimidation and exploitative labour conditions.

To think about violence in multispecies terms, brings us to consider situations where humans are not the only culprits, and non-humans not the only victims.

Oil palm’s acts of violence invite us to think about non-human beings as drivers and perpetrators of harm – even as they themselves are also subject to human and technological manipulations and exploitation.

Paraquat, a deadly herbicide, trickled down from rusty canisters strapped to the women’s backs, the blue-green venom seeping into their exposed skin.

Banned in many countries because of its toxic effects, no antidote exists for this lethal chemical. I thought of babies never to come. The faces of my friends, huddled in the bed of the truck, were caked in dust and watched the landscape unfurl, weeping.

Infants retched from the stench of mill effluents as we jolted down dirt roads without stopping so as to avoid attracting the attention of military men employed by the companies to guard their plantations. Bunches of oil palm fruit lay strewn along roadsides, piles of moldering blood-red and coal-black, shot through with razor-sharp thorns.

Bulldozers and chainsaws ripped through isolated patches of the remaining vegetation. Silhouetted against the bleary sun, pesticide-spraying helicopters zigzagged back and forth above us, spreading a milky veil of hazy toxins.

~ Dr Sophie Chao, excerpt from the prologue of ‘In the Shadow of the Palms.’

The day that MIFEE came

On August 11th 2010, a delegation of government representatives from Jakarta, led by the then minister of agriculture Ir. H Suswono launched the Merauke Integrated Food and Energy Estate (MIFEE). A $5 billion USD agribusiness scheme to promote the country’s self-sufficiency in basic foodstuffs and to make Indonesia a net food-exporting nation. Papuans from across the region were invited to the event including Marind community members from the upper Bian river. Paulus Mahuze, Marind clan leader recalls the arrival of MIFEE and how everything changed dramatically afterwards for his people.

~ Dr Sophie Chao, excerpt from her book ‘In the Shadow of the Palms.’

“It was a hot day. There was dust (abu) everywhere, raised by the government convoys and military trucks. The dust stung our eyes and made our children cry. The government brought oil palm (sawit) company bosses with them from pusat (‘the centre,’ or Jakarta). They gave us instant noodles, pens, bottles of water. They also gave us cigarettes – the expensive kind. They talked a lot about MIFEE. MIFEE this, MIFEE that…but we didn’t understand what MIFEE was. We did not know what palm oil was because oil palm does not live in our forests. Then, the government officials and the oil palm bosses left. They never returned to the village.

~ Paulus Mahuze, marind clan leader (as told to dr sophie chao in her book: In the shadow of the palms).

They promised us money and jobs. They said MIFEE would provide us with food. I thought that they would plant yams, vegetables and fruit trees. Instead they planted oil palm. They planted oil palm everywhere they could. They turned the whole forest into oil palm. They cut down all the sago to plant oil palm. This is what happened. Since then, everything is abu-abu (‘grey’ or ‘uncertain’).

Abu-abu means both “grey” and “uncertain”. For Marind, the future, hope and multispecies relations were all abu-abu and under siege

Pictured: Oil palm plantations in Merauke have contributed to unprecedented levels of deforestation, and water/soil contamination. Photo credit: Dr Sophie Chao.

The concept of abu-abu is one that many of my Marind friends would use to describe the worlds that they inhabit

Abu-abu communicates the sense of ambiguity, opacity, and strangeness that life on the palm oil frontier entails. Greyness manifests in the polluted waters of local rivers, and in the smoke-filled skies following forest burning.

Greyness also manifests in the dull and irritated skin of malnourished infants, poisoned fish, and pesticide-wielding workers

To live in a world of murk and uncertainty is violent and unsettling – but it is also a way of rejecting the possibility of any kind of radical divide between oneself and that murk. That’s why I approach abu-abu not just as a condition of suffering, but also as a stance of refusal.

What would or might come next for Marind and their other-than-human kin was unknown – and often feared.

This sense of greyness, or uncertainty is also metaphorical. For Marind the world is grey in that the future, hope, social and multispecies relations are all under siege.

Pictured: Dead fish, creative commons image, Pxfuel.

At the same time, abu-abu was a form of resistance in the way it refused fixed classifications, categories, or boundaries between things, ideas, and actions

Whether “sustainable” palm oil can be achieved in practice demands a radical rethinking of the capitalist logic – the logic of endless growth

Careless profit-making, and externally imposed “development” and “progress” rhetorics. And that is a huge task. These kinds of rhetorics are deeply entrenched. Their origins are often unquestioned. Their impacts are often silenced.

At the end of the day, I think the most important thing to ask ourselves about “sustainability” is – sustainability for whom?

Who gets to have a say over what happens to lands and forests? Who gets to be involved in decision-making processes surrounding oil palm projects? Is there scope to reconsider the scale at which these projects are being developed?

These are questions that have to be crafted and considered together with the Indigenous peoples most directly and indirectly affected by agribusiness expansion.

That, for me, is the beginning of any kind of conversation around sustainability – sustainability for people, plants, animals, and for all the other beings implicated in one way or another in the palm oil nexus.

The rationale for additional Food Estates in Papua and Indonesia is scrutinised in this 2022 report

“The rationale behind Food Estates, that they are an effective way to rapidly increase national food production, does not stand up to scrutiny.

“Over the years, previous attempts to launch Food Estates have failed, with little if any extra food produced. The various iterations of the Merauke Food Estate (MIFEE) are a good example of this.

“For these reasons, it is legitimate to call into question the real motivation behind the plans. With corruption still rampant in Indonesia, there is a significant risk that Food Estates will present new opportunities for profit by those in government and their associates.”

Quote from: Pandemic Power Grabs: Who benefits from Food Estates in West Papua, a report by AwasMIFEE and TAPOL (2022).

Upcoming online events and publications

Event: Eating and Becoming Eaten More-than-human metabolisms on the West Papuan Agribusiness Frontier

The Promise of Multispecies Justice

Edited by Dr Sophie Chao, Karin Bolender, Eben Kirksey.

What are the possibilities for multispecies justice? How do social justice struggles intersect with the lives of animals, plants, and other creatures? Leading thinkers in anthropology, geography, philosophy, speculative fiction, poetry, and contemporary art answer these questions from diverse grounded locations.

You can find and follow me on Twitter if you wish @Sophie_MH_Chao

Pictured: Dr Sophie Chao researched the life of the Marind-Anim tribe in Merauke for three years. Her doctoral dissertation on the impact of oil palm plantations on the lives of the tribe won the 2019 best thesis award in Australia in the field of Asian Studies. Photo: ABC News Indonesia

Images: Getty Images, Dr Sophie Chao, Nanang Sujana, Craig Jones Wildlife Photography, ABC News Indonesia.

Words: Dr Sophie Chao

Further Reading

‘In West Papua, oil palm expansion undermines the relations of indigenous Marind people to forest plants and animals’ by Dr Sophie Chao for The Conversation.

After 75 years of independence, Indigenous Peoples in Indonesia still struggling for equality by Dr Sophie Chao for The Conversation.

‘Kelapa Sawit Membunuh Sagu’: Sophie Chao Meraih Tesis Terbaik di Australia Setelah Meneliti Suku di Papua by Farid M. Ibrahim for ABC Indonesia.

In the plantations there is hunger and loneliness: The cultural dimensions of food insecurity in Papua (commentary)’ by Dr Sophie Chao for Mongabay.

The sky has no corners: My journey to a new understanding of nature, an essay by Dr Sophie Chao for Five Media.

Read and watch more stories about indigenous justice, land-grabbing and deforestation on Palm Oil Detectives

Mama Malind su Hilang (Our Land is Gone) by filmmaker Nanang Sujana

Image: Marind children in Merauke West Papua by Nanang Sujana

Mama Malind su Hilang (Our Land Has Gone) is a powerful documentary by celebrated and renowned filmmaker and photographer Nanang Sujana. His images and film tells the story of the Malind Anim tribe living in Zanegi village. They were dispossessed from their land which was given over to global palm oil corporations, in its place was Merauke Integrated Food and Energy Estate (MIFEE).

“The Forest is the father, land is the mother and rivers are blood

“That’s the spirituality of most Dayak people in Kalimantan. They understand the interdependent nature of everything in nature.”

~ Dr Setia Budhi : Dayak Ethnographer

Image: Rainforest in Sumatra by Craig Jones Wildlife Photography

Palm Oil Detectives is 100% self-funded

Palm Oil Detectives is completely self-funded by its creator. All hosting and website fees and investigations into brands are self-funded by the creator of this online movement. If you like what I am doing, you and would like me to help meet costs, please send Palm Oil Detectives a thanks on Ko-Fi.

well done! thanks so much.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks very much Mary

LikeLiked by 1 person

I found it very interesting that to the Marind people, conservation and capitalism are two sides of the same coin. I understand this meaning that to the Marind people, the necessity of the term ‘conservation’ in itself indicates an anthropocentric consciousness. Conservation becomes a way to ‘offset’ harmful actions brought to the environment by capitalist goals and intentions. To them, the importance of ecological balance and respect for the environment (and the non-human beings in it) precedes any economic and political objective – therefore there is no need for conservation.

This makes me realise the effect of values and beliefs in a culture in creating conflict with other cultures. It is the different set of priorities in the cultures of the Marind people and the economic palm oil agents that makes this issue much more difficult to resolve peaceably for both parties.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Carina for this insightful and in-depth response to this issue. The prerogative of the palm oil industry is the same as rampant unchecked capitalism in general. This is to obtain land at the cheapest price and by whatever means are necessary, trampling upon the rights of indigenous peoples throughout the world has been the ongoing legacy of the palm oil industry and all other food and agriculture sectors- especially meat, soy, cocoa and coffee. Unlike toothless and useless industry certifications which are nothing more than facilitators and promoters of greenwashing, legal action and suing big business that causes ecocide along with strong action from policy makers like what is happening in the EU are very effective in stopping the deforestation for timber and palm oil in Papua and many other places. The #EUDR for the European Union has crippled the palm oil industry’s growth and thank goodness for that. More remains to be done to make the lives of Papuan people become visible in the West and kept in mind all of the time! #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Indigenous #Boycott4Wildlife

LikeLiked by 1 person