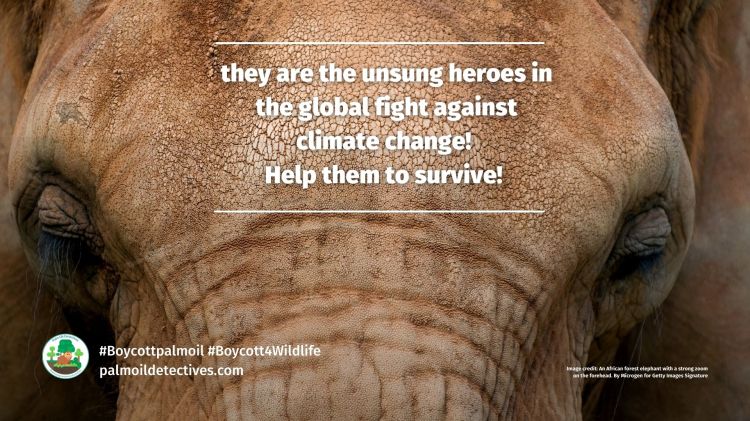

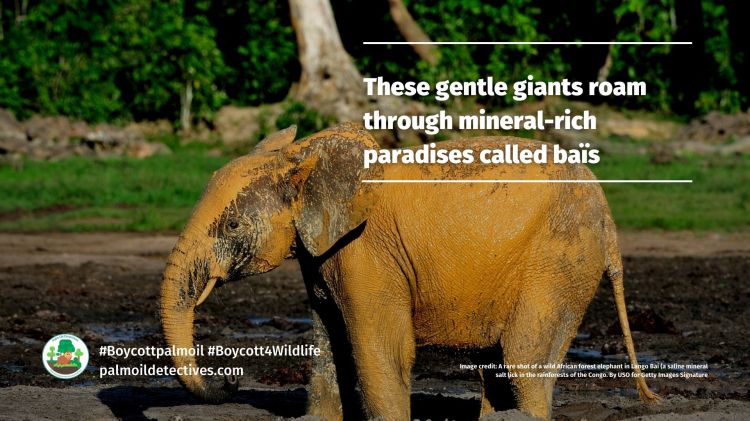

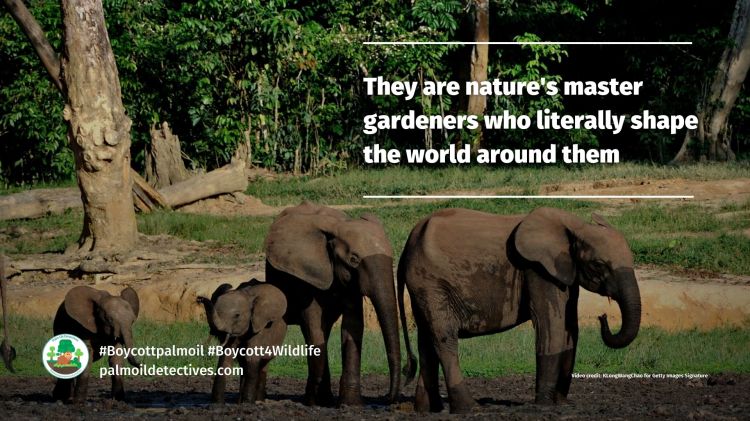

Discover the awe-inspiring role of African forest elephants in the Congo Basin—nature’s master gardeners who literally shape the world around them! These gentle giants roam through muddy, mineral-rich paradises called baïs, fostering the growth of carbon-absorbing trees that make our planet healthier. By tending to these unique landscapes, they are the unsung heroes in the fight against climate change. Want to ensure these ecological architects keep doing their vital work? Join the movement to protect their habitat—say no to palm oil and adopt a vegan lifestyle! 🐘🌳#BoycottPalmOil #BeVegan #Boycott4Wildlife

Take action by sharing this to Twitter!

African forest #elephants 🐘 in #Congo 🇨🇩 are essential to fighting #climatechange 🌳💚 by capturing #carbon and dispersing seeds in the rainforest. Help them every time you shop, be #vegan #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://wp.me/pcFhgU-6Le

Gentle giant pachyderms #African forest #elephants 🐘🐘 are the unsung heroes helping #climatechange. They capture #carbon in the #DRC’s 🇨🇩🌳rainforest! Help them survive with your supermarket choices #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://wp.me/pcFhgU-6Le

This story was written by Leonie Joubert and originally published by Mongabay on August 15, 2023 and was republished under a Creative Commons licence.

The approach to the “village of elephants” in the Sangha Rainforest in the Central African Republic must be made in complete silence. Not even the faintest rustle of backpack on rain jacket should break the soundscape as visitors wade through the sometimes waist-deep swamp at the forest’s edge. The Indigenous Ba’aka guides must be able to listen for any signs of nearby elephants, so they can steer the visitors clear and avoid a close encounter with these giants. When a few pachyderms saunter out of the dense greenery, the Ba’aka shoo them away calmly.

The thick vegetation gives way suddenly to a baï. This is no mere watering hole. The sandy clearing stretches for half a kilometer, more than a quarter of a mile, in the otherwise unbroken canopy of the world’s second-largest tropical forest.

A handful of researchers camp out on a timber observation platform, overlooking a place that has drawn generations of elephants to its mineral- and salt-laden sand and muddy water. They document how the animals use their trunks or tusks to dig into the sand, eavesdrop on the animals’ conversations, and count the many other species that congregate here.

This is Dzanga baï, a meeting place for critically endangered African forest elephants (Loxodonta cyclotis) in the Dzanga-Sangha Complex of Protected Areas where these animals come together in huge numbers to dig for nutrients they can’t get from the otherwise abundant forests.

Baïs are unique to the Congo Basin’s forests, and new research is underway to understand the role these mineral-rich pockets play as a supplement to the elephants’ diet, how this sustains the animals’ population, and how they therefore contribute to the carbon-capture function of the forest.

Unlike the Amazon, the Congo Basin’s forests still have their original megafauna, elephants in particular. And they have these salt-rich clearings. Conservationists are beginning to understand the importance of elephants as forest gardeners here, and how their taste for certain trees and fruits has sculpted a forest that absorbs more carbon per hectare than the Amazon.

The Global Carbon Budget project estimated Africa’s total greenhouse gas emissions for 2021 at 1.45 billion metric tons. Every year, the Congo Basin’s forests soak up 1.1 billion metric tons of atmospheric carbon, storing it in trees and soil; in 2020 carbon credit prices, this service would be worth $55 billion.

Forest elephants, smaller than their better-known savanna cousins or even Asian elephants, prefer certain lower-growing, tasty trees. This picky browsing pressure creates gaps in the canopy that allow other, less palatable but carbon-dense species to reach tremendous heights. Elephants’ appetite for the fruit of these bigger trees then means they spread their seeds far and wide.

A 2019 study from the Ndoki Forest in the Republic of Congo (ROC) and LuiKotale in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) estimated that if elephants were removed from these sites, the loss of their forest-shaping food preferences would reduce the forest’s carbon capture by 7%.

This finding makes a case not only to stop deforestation in the Congo Basin, but to protect the elephants too, as a way to slow climate breakdown, the study authors wrote.

Salt licks for elephants, gardeners of the forest

Mouangi baï is only about 250 km (155 mi) from Dzanga baï as the crow flies, but it takes a day or two to travel by road and river to get from one to the other.

Researchers with the conservation organization African Parks and Harvard University’s Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology are zeroing in on Mouangi and other baïs in Odzala-Kokoua National Park in the ROC, to clarify the link between baïs, elephants and the forest’s tree species composition.

Nicknamed Capitale by the locals, Mouangi baï in Odzala draws hundreds, maybe even thousands, of elephants, according to Gwili Gibbon, research and monitoring head at African Parks, which manages the park along with the ROC government.

“Mouangi is one of our largest and most renowned baïs,” Gibbon says.

At the intersection of two rivers, Mouangi is more than 1 km (0.6 mi) across and spans 91 hectares (225 acres). It’s the largest of a dozen of Odzala’s baïs that the African Parks and Harvard research collaboration is focusing on.

Odzala-Kokoua National Park extends across 1.35 million hectares (3.34 million acres), and while it has a few thousand baïs, often occurring in clusters within the forest, this ecosystem makes up only about 0.2% of the park’s footprint. Nevertheless, these clearings may be integral to the shape of the forest itself, which is why Harvard assistant professor Andrew Davies and doctoral researcher Evan Hockridge are teaming up with African Parks to understand the importance of the salty watering holes in supporting elephant populations, which then shape the forest mosaic.

The baïs are clearly a hotspot that elephants seek out for their rare minerals in an ecosystem rooted in the nutrient-poor soils typical of the region.

“The elephants use their tusks to scrape topsoil off in specific areas, and eat the finer dust on the surface,” says Hockridge, a landscape ecologist. “They also dig large mining sites or wells, as much as a meter [3 feet] deep.”

The animals’ excavations go even deeper at times, down to where water carries the salt in a more accessible form. The need to ingest the mineral-rich dust, mud and water keeps the animals returning to these sites.

But how the baïs formed in the first place — they’re present in the Congo Basin, but not in the Amazon — and why they remain clear of forest encroachment are still a mystery.

Hockridge says no one has tried to establish if the now-extinct megafauna of the Amazon once made similar clearings there, or if baï size correlates to the size of the animals visiting them.

“One hypothesis is that megafauna effectively create large, nutrient-rich, lick-like clearings. But it hasn’t been quantified that baïs are manufactured or maintained by megafauna,” he says.

The researchers say they hope to answer this puzzle: Do large mammals like elephants maintain and stabilize the baïs?

Anecdotes from the DRC might give the first glimpse of an answer, according to Harvard’s Davies.

“Baïs may be closing in the DRC, and it could be because the elephants are in a war zone, so they don’t have the big bulldozer effect,” he says.

The hypothesis is that if fewer elephants visit and maintain these clearings, the baïs will be swallowed up by the forest.

Gibbon’s African Parks team has set up experimental plots in the Odzala, where they’ve buried salt in the sand at a similar depth to which elephants excavate. Researchers are monitoring these sites to see if more animals will congregate around the plots, whether this impacts the vegetation cover in and around the baïs, and whether there’s a shift in the carbon-capture potential of the surrounding forests.

This study is centered in Odzala, although the researchers say they hope to expand the work into the Ndoki region of the Dzanga-Sangha Complex of Protected Areas.

Baïs have a busy social scene

It isn’t just elephants that congregate at the baïs. These watering holes have a bustling social scene.

Gibbon describes the flocks of African green pigeons (Treron calvus) that gather at Capitale at dawn and dusk; buffalo and several bird species that visit during daylight hours; and the hyenas that can be heard calling after dark as the elephants mine for salt.

Wildlife refuges like these in the Congo Basin are also home to the critically endangered western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla), two unusual forest and swamp-dwelling antelope — the bongo (Tragelaphus eurycerus) and sitatunga (Tragelaphus spekii) — as well as central chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes troglodytes), bonobos (Pan pansicus), and the endangered gray parrot (Psittacus erithacus).

The forests of Gabon, southern Cameroon and southern Central African Republic also have a high number of baïs, and the findings from these studies could eventually be extrapolated to give an idea of the implications for the Congo Basin more widely.

“The area that baïs’ cover is tiny, but they sustain the elephant population,” Davies says. “If our hypothesis is correct, without the baïs you’d have no elephants; without elephants there’s be no big trees with high carbon density, so carbon storage would go down.”

If the forest loses the baïs, it could lose more than just the elephants or see a change in its carbon-capturing treescape. The baïs would no longer draw the many other animals that thrive in these mineral-dense watering holes, and the tourists and environmental researchers drawn to them too.

Citation:

Berzaghi, F., Longo, M., Ciais, P., Blake, S., Bretagnolle, F., Vieira, S., … Doughty, C. E. (2019). Carbon stocks in central African forests enhanced by elephant disturbance. Nature Geoscience, 12(9), 725-729. doi:10.1038/s41561-019-0395-6

Banner image: Elephants dig for salt-rich mud in the Dzanga baï in the Sangha Rainforest in the Central African Republic. Image courtesy Jan Teede.

This story was written by Leonie Joubert and originally published by Mongabay on August 15, 2023 and was republished under a Creative Commons licence.

ENDS

Learn about other animals endangered by palm oil and other agriculture

Learn about “sustainable” palm oil greenwashing

Read more about RSPO greenwashing

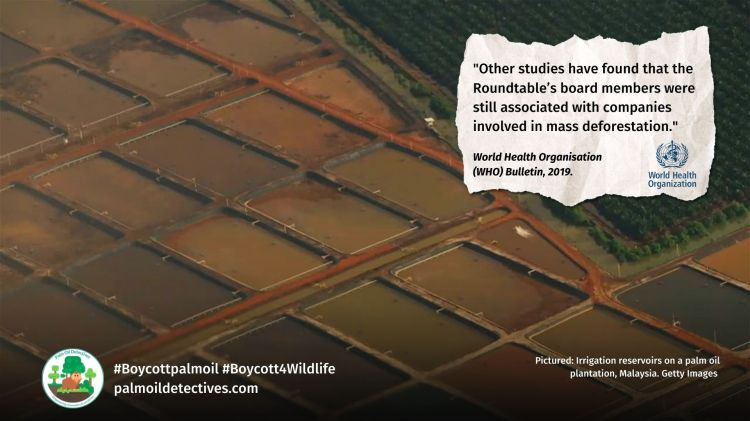

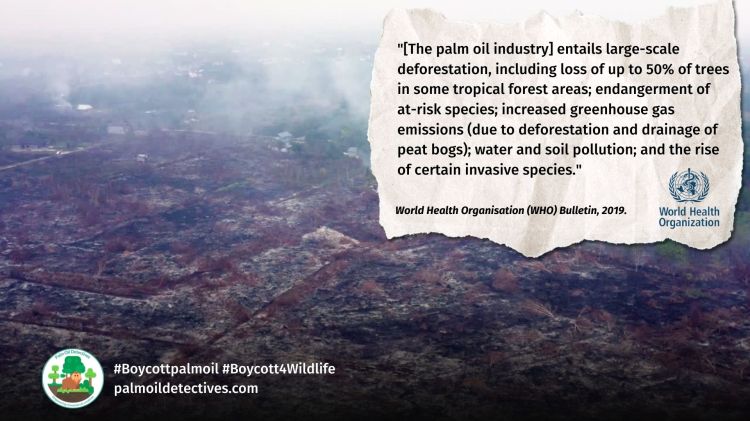

A 2019 World Health Organisation (WHO) report into the palm oil industry and RSPO finds extensive greenwashing of palm oil deforestation and the murder of endangered animals (i.e. biodiversity loss)

Contribute in five ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here