Aviary Doert holds a Bachelor’s of Science in Biology and they have worked for a decade in medical and laboratory science. They are an amateur conservation scientist, with experience in field work and research. They are hoping to positively impact the environment and planet through education and increasing awareness of the consequences of people’s purchases and actions.

A Social, #Ethical Environmental #History of #Coffee by Aviary Doert/@SnowRiver66 who demystifies the origins and impact of the world’s most loved cup of liquid motivation #Boycott4Wildlife

Tweet

Facts and history of coffee

- ‘Coffea’ is the genus name for the flowering, perennial, evergreens in the family Rubiaceae. ‘Coffea’ species are native to tropical and southern Africa and tropical Asia.

- The coffee plant was first said to have been discovered in Ethiopia (known then as Abyssinia). Coffee then made its way north, across the red sea into Yemen in the 15th Century.

- The major port used was in the city of “Mocha” – hence the term’s current association with coffee.

- Coffee cultivation and trade flourished on the Arabian Peninsula, and by the 15th century coffee was being grown in the Yemeni district of Arabia.

- By the 16th century it was known in Persia, Egypt, Syria, and Turkey. Then coffee spread East into India and Indonesia, and West into Italy (in 1570) and the rest of Europe.

- It wasn’t until 1822 that coffee production started to boom in Brazil, and in 1852 the country became the largest producer of coffee and has remained such to this day. Hawaii (not part of America until 1959) was introduced to coffee in 1817 when coffee seedlings were brought by the Brazilians. In 1825, the first official coffee orchard was born, starting Kona’s legacy in the industry.

The Plant

Coffee is a plant in the Family Rubiaceae and Genus Coffea and grows from seed – the coffee bean. These plants range from small shrubs to up to 8 metres tall depending on the species and cultivar. Of all 100 species of the genus Coffea, only a few are commercially used. Coffea arabica and C. canephora (of which the main variety is Robusta), supply almost all of the world’s cofee consumption.

Arabica

Arabica makes up around 70% of all coffee consumption. The species is a 3-4 metre tall bush with dark-green oval leaves and fruits (or cherries) that take around 7 to 9 months to mature. Arabica are able to self-pollinate and are considered more mild, flavourful and aromatic brew than Robusta, and have a lower caffeine content.

Robusta

Robusta makes up the remaining 30% of the world’s coffee production. The tree can grows to 10 metres tall and its fruits take around 11 months to mature. Robusta is hardier than Arabica and can flourish in hotter, harsher conditions. Western and Central Africa, Southeast Asia, and Brazil are major producers of Robusta coffee. This coffee is cheaper to produce and has twice the caffeine content of Arabica, which makes Robusta the bean of choice for inexpensive commercial coffee brands. You will recognise its flavour as being the stronger, more bitter brew than Arabica.

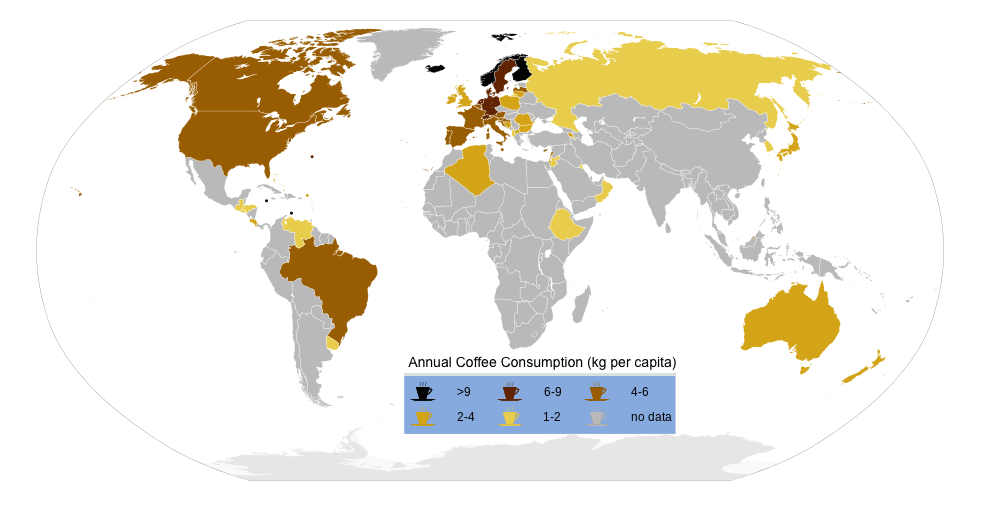

Which countries drink the most coffee?

The world’s 10 top coffee importing countries by dollar value in 2020 (listed below as US dollars):

- The EU imports around 40% of the world’s coffee beans

- The United States is the world’s second-largest importer of coffee beans.

- United States: US$5.7 billion (18.3% of total coffee imports)

- Germany: $3.5 billion (11.4%)

- France: $2.9 billion (9.3%)

- Italy: $1.5 billion (4.8%)

- Canada: $1.21 billion (3.9%)

- Netherlands: $1.19 billion (3.8%)

- Japan: $1.18 billion (3.8%)

- Belgium: $1.13 billion (3.6%)

- Spain: $1.01 billion (3.3%)

- United Kingdom: $1 billion (3.2%)

The world’s most caffeinated people

10 biggest coffee drinking countries in pounds/kilograms per capita (person) per year in 2020:

Finland – 12.02kg (26.5 lbs)

Norway – 9.89kg (21.8 lbs)

Iceland – 8.98kg (19.8 lbs)

Denmark – 8.70kg (19.18 lbs)

Netherlands – 8.39kg (18.5 lbs)

Sweden – 8.16kg (18 lbs)

Switzerland – 7.89kg (17.4 lbs)

Belgium – 6.76kg (14.9 lbs)

Luxembourg – 6.35kg (14 lbs)

Canada – 6.21kg (13.7 lbs)

Where is coffee grown?

More than 70 countries produce coffee, but the majority of global output – 74.3% – comes from just the top five producers: Brazil, Vietnam, Colombia, Indonesia, and Ethiopia.

Statistical data from 2020:

- Brazil – 3,804,000 metric tonnes (produces a third of the world’s coffee)

- Vietnam – 1,740,000 metric tonnes

- Colombia – 858,000 metric tonnes

- Indonesia – 720,000 metric tonnes

- Ethiopia – 438,000 metric tonnes

- Honduras – 366,000 metric tonnes

- India – 342,000 metric tonnes

- Uganda – 336,000 metric tonnes

- Mexico – 240,000 metric tonnes

- Peru – 228,000 metric tonnes

Deforestation

Global forest loss is a huge problem around the world. An estimated 15 billion trees are cut down every year.

Nearly all – 95% – of this deforestation occurs in the tropics. 14% of deforestation is driven by consumers in the world’s richest countries – importing beef, vegetable oils, cocoa, coffee and paper that has been produced on deforested land. In 2019, 12.2 million hectares of tropical forests were lost.

Although the precise area is debated, each day at least 80,000 acres (32,300 ha) of forest disappear from Earth. At least another 80,000 acres (32,300 ha) of forest are degraded.

Forest loss in the Amazon jungle: the lungs of the planet

Tropical forests presently cover about 1.84 billion hectares or about 12% of Earth’s land surface (3.6% of Earth’s surface).

Why are forests lost?

- Commodity-driven deforestation: The long-term, permanent conversion of forests to other land uses, typically agriculture (including coffee plantations, oil palm and cattle ranching), mining, or energy infrastructure.

- Urbanisation: The long-term, permanent conversion of forests to towns, cities, roads and infrastructure.

- Shifting agriculture: Small to mid-scale conversion of forest for farming, that is later abandoned so that forests regrow.

- Forestry production: for timber, paper and pulp.

- Wildfires: Short term disturbances to forests that are likely to regrow.

95% of the world’s deforestation occurs in the tropics

In Latin America and Southeast Asia in particular, commodity-driven deforestation – mainly the clearance of forests to grow crops and pasture for beef production – accounts for almost two-thirds of forest loss.

Coffee deforestation

The equatorial area between the Tropic of Capricorn and the Tropic of Cancer is ideal for growing coffee and is known as the “coffee bean belt”. All coffee-growing countries are very rich with biodiversity (rare and endemic plant and animal species).

Globally, coffee production increased by 24% between 2010 and 2018

This equates to around 2 million metric tons that is primarily destined for developed nations such as the UK (3%), the USA (16%), and the EU (44%). Asia is also a growing market. The demand for coffee is expected to grow between 50%-163% by 2050.

Coffee plantations, especially those using the sun-grown mass production method, have caused massive deforestation.

2.5 million acres of forest in Central America alone have been cleared so far for coffee plantations. Brazil has been the world’s largest producer of coffee for the last 150 years.

Over two million hectares of Brazilian land are currently dedicated to coffee, producing an average of 43 million bags of coffee a year.

In Vietnam, coffee is a growing industry The coffee growing area of Vietnam is at least 600,000 hectares. According to data from Global Forest Watch, Indonesia lost 9.75 million hectares of primary forest between 2002 and 2020. In 2016, a record 929,000 hectares of forest disappeared; by 2020, the annual loss decreased to 270,000 hectares.

Seven out of ten coffee-producing countries have some of the world’s highest rates of primary forest loss

This is occuring in tropical countries: Brazil, Indonesia, Peru, Colombia, India, Mexico and Vietnam.

Coffee plantations cause massive deforestation as the world’s demand for it has increased exponentially over the past few decades. 37 of the 50 countries in the world with the highest deforestation rates are also coffee producers.

Aside from coffee tropical countries clear forests and habitats for soy (for cow feed), cattle ranching, palm oil & coconut oil plantations and mining, to name a few.

Coffee deforestation and species loss

Tropical rainforests are incredibly rich ecosystems that play a fundamental role in the basic functioning of the planet.

- Around 50% of the world’s terrestrial species live in rainforests: Our planet is losing untold numbers of species to extinction, the vast majority of which have never been documented by science.

- Rainforests maintain the climate: By regulating atmospheric gases and stabilizing rainfall, protect against desertification, and provide numerous other ecological functions.

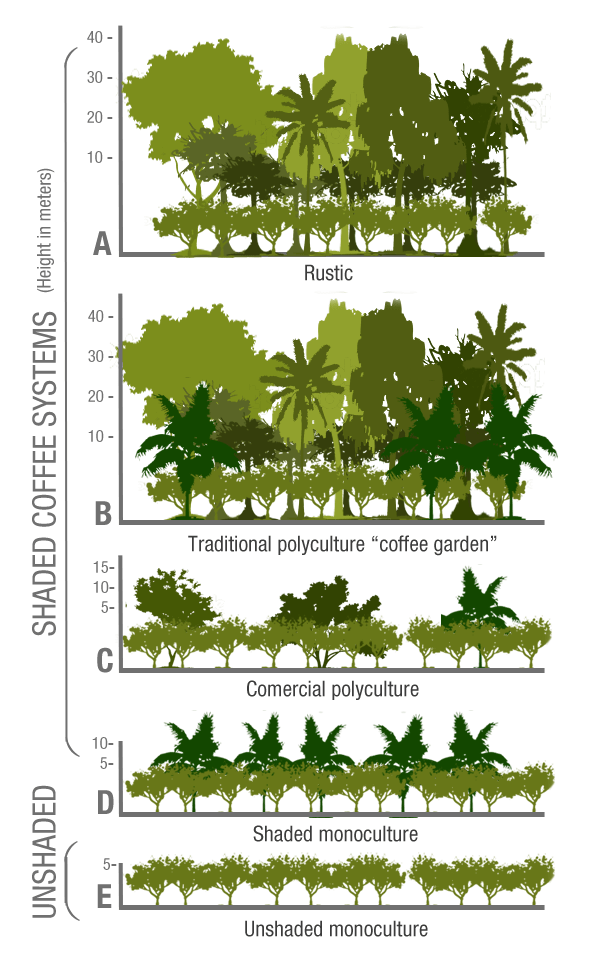

Species richness is lower in most coffee agroecosystems than in natural forests

Many research studies of mammals, insects and birds have shown these species are greatly reduced on coffee plantations. There are three kinds of coffee cultivation practices:

- Fully rustic coffee: where coffee plants are grown interspersed with forest trees and understory – has the least impact non biodiversity.

- Shade-grown monoculture: is a slightly more intensive technique, farming larger densities of coffee plants underneath the forest canopy. This impacts biodiversity more than rustic coffee.

- Sun-grown coffee: Involves the clearance of the forest, removing epiphytic plants from the coffee trees, and applying chemical fertilizers. This has the greatest negative impact on biodiversity.

Across studies, mammal, bird and insect biodiversity declined in coffee plantations. The richness of migratory and foraging bird species was less affected by coffee production than that of resident, canopy and understory bird species. Loss of species also depended greatly on habitat specialisation and functional traits.

Endangered species impacted by coffee production in South America

The Scarlet Tanager, Gray Catbird, Eastern Wood Pewee, Wood Thrush Canada Warbler, Cerulean Warbler, Olive-sided Flycatcher and the near-threatened Golden-winged Warbler. These bird species are being affected by loss of both breeding and wintering grounds.

Research specifically on other species affected by coffee plantations, such as mammals, is less available. One can extrapolate and hypothesize, however, that the loss and degradation of habitat affects all species living there.

Coffee: Agriculture and Animal Exploitation

Certain coffee trends are associated with animal exploitation. This stems from the practice of feeding coffee beans to certain animals and then using the excreted beans for consumption.

“Civet coffee” or Kopi luwak

This involves the Asian palm civet, a small mammal found in the jungles of Asia. The Indonesian coffee is produced by feeding coffee beans to the civet and using the excreted beans. Producers claim the civet’s digestion process improves the beans’ flavor. It is the most expensive coffee in the world, selling for hundreds of dollars per pound. A single cup can cost up to US$80.00.

Asian Palm Civets – Wild and Caged

The popularity of so-called “civet coffee” has led to intensive farming of the animals, who are confined in cages and force-fed the beans.

Sign the petition to end civet coffee farming

sk the Indonesian government to place regulations on the treatment of wild Asian palm civets and ban the inhumane production of civet coffee!

The very popular and expensive Indonesian civet coffee is still being produced despite proof of inhumane conditions.

In order to harvest the coffee, farmers feed seeds of coffee berries to imprisoned Asian palm civets, a beautiful wild cat-like mammal, and gather the seeds again from their excrement. The civets are captured from the wild, torn from their families, held in tiny, sometimes dark, cages, and are often force-fed the berries. There are currently no regulations in place on how to treat these animals, and farmers will often feed them to death with no concern for their health or living conditions.

Demand that the Indonesian government acknowledge this catastrophe and vow to end the cruel production of civet coffee!

It has been documented that many of the civets in the coffee industry have no access to clean drinking water, no ability to interact with other civets, and live in urine- and feces-soaked cages. Many are forced to stand, sleep, and sit on wire floors, which causes sores and abrasions. Some civets also exhibit signs of zoochosis, “a neurotic condition among stressed animals in captivity. The signs include constant spinning, pacing and bobbing their heads.”

Black Ivory Coffee: Elephant exploitation for coffee

A similar process is used in the nascent practice of feeding coffee beans to elephants. Sadly, it’s being carried out at a “sanctuary” in Thailand, where around 30 elephants consume beans from nearby plantations. Branded as Black Ivory Coffee, this expensive brew (about US$50 per serving) doesn’t yet have the popularity of civet coffee, and producers argue the animals are in no way harmed, but it points to a disturbing trend in animal exploitation.

Coffee: Human Rights and Labour Abuses

As with many other industries in the developing world, there are rampant human rights abuses associated with coffee cultivation and production.

The coffee business is tied to a long history of colonialism and slavery.

Low Wages, Abusive Conditions and Child Slavery

Many times farmers and workers in the coffee industry are paid poverty wages, with the profits going to those higher up in the corporate hierarchy.

Coffee farmers typically earn only 7–10% of the retail price of coffee, while in Brazil, workers earn less than 2% of the retail price. To earn enough to survive, many parents pull their children from school to work on the coffee plantations. Child slavery is widespread in coffee cultivation. When the price of coffee rises, the incentive for struggling families to withdraw their children from school and send them to work increases; at the same time, a fall in coffee prices increases poverty in regions that depend on the crop, which can also prevent children from attending school.

Conditions on the farms are quite different from what is promised. Few of the lodgings had running water and in some cases, there were not even any beds or toilets. In their testimonies, workers describe conditions as like ‘living in a corral’, with poor sanitation, in precarious structures that were not enough to meet even the most basic needs for dignified survival.

A cycle of poverty

Since higher levels of education are tied to higher income over the long term, and children from poor families are those most likely to be sent to work rather than school, child labor maintains a cycle of poverty over generations.

A study in Brazil found that child labour rates were approximately 37% higher, and school enrollment 3% lower, than average in regions where coffee is produced.

Children as young as six years old often work eight to 10 hours a day and are exposed to the many health and safety hazards of coffee harvesting and processing, from dangerous levels of sun exposure and injuries, to poisoning from contact with agrochemicals.

‘Slave labour on coffee farms denounced at the OECD’, Connectas Human Rights

During the coffee-harvesting season in Honduras, up to 40% of the workers are children. Children, and women, are hired as temporary workers and are therefore paid even less than adult male workers. In Kenya, for instance, these “casual” workers often only make about $12.00 a month. Even though there are family farms where children might participate in light labor for part of the day, regulations against child labor do exist in coffee-producing countries, but economic pressures make authorities in these regions reluctant to enforce the law.

“We went hungry, because they didn’t pay and they didn’t register us either. So we were stuck there. If those people hadn’t got us out we would have stayed there for ages.”

‘Slave labour on coffee farms denounced at the OECD’, Connectas Human Rights

Exposure to pesticides, pollution and chemicals

Additionally, in areas with sun-grown coffee, more chemical fertilisers, agricultural chemicals, and fungicides are required. Given the levels of poverty in the areas where coffee is grown, workers are often unable to afford protective equipment that would limit their exposure; in other cases, they simply choose not to use it or are not aware that it is necessary. Many workers complain of difficulty breathing, skin rashes, and birth defects.

Indentured slavery

Many coffee workers are effectively enslaved through debt peonage, which is forced labor to repay debts. Landed elite in coffee-producing regions own large plantations where a permanent workforce is employed.

The workers are forced to buy from a plantation shop for their everyday needs that has over-inflated prices. Since they earn less than minimum wage, they become indebted to their employers. It is common for families who are part of the permanent labor force on a plantation to work and live there for generations, in order to pay back debts for renting their homes, land or health costs. In Brazil, hundreds of workers are rescued from slave-like conditions annually.

Coffee brands and slave labour for coffee

In 2016, two of the world’s largest coffee companies (accounting for 39% of the global coffee market), Nestlé and Jacobs Douwe Egberts, acknowledged that slave labor is a risk in their Brazilian supply of coffee. Nestlé admitted they purchase coffee from two plantations with known forced labor and they cannot “fully guarantee that it has completely removed forced labour practices or human rights abuses” from their supply chain.

Coffee: Environmental Certifications

There are a number of coffee certification schemes that encourage environmental farming practices and inform consumers about which companies and brands follow these practices.

Often the concept is very good. However the real life implementation and enforcement of the standard is severely lacking.

Research finds that certification schemes are merely greenwashing tools – they do not improve equity outcomes or prevent deforestation

It should be noted that many NGOs that work to analyse certification schemes such as Greenpeace, ECCHR Berlin and the Environmental Investigation Agency have found that certification standards are overall insufficient, weak and merely a consumer marketing tool rather than a tool for ameliorating human rights abuses or stopping deforestation.

Eco-labels and certifications for agricultural crops have yet to halt land use change. Sparse and uneven market uptake only partially explain this outcome. Loopholes in certification standards and enforcement mechanisms also play a role.

Do eco-labels prevent deforestation? Lessons from non-state market driven governance in the soy, palm oil, and cocoa sectors., (2018) van der Ven, H., Rothacker, C. & Cashore, B. Glob. Environ. Change 52, 141–151.

We find that, while sustainability standards can help improve the sustainability of production processes in certain situations, they are insufficient to ensure food system sustainability at scale, nor do they advance equity objectives in agrifood supply chains.

Sustainability standards in global agrifood supply chains., (2021) Meemken, EM., Barrett, C.B., Michelson, H.C. et al. Nat Food. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-021-00360-3

Instead of guaranteeing that deforestation and other harms are excluded from supply chains, certification with inadequate governance, standards and/or enforcement enables destructive businesses to continue operating as usual.

More broadly, by improving the image of forest and ecosystem risk commodities and so stimulating demand, certification risks actually increasing the harm caused by the expansion of commodity production.

Instead of being an effective forest protection tool, certification schemes thus end up greenwashing products linked to deforestation, ecosystem destruction and rights abuses.

Destruction Certified, Greenpeace 2021.

Smithsonian Bird-Friendly

Developed by ecologists at the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center; has the strictest habitat requirements of any coffee certification.

Goals

- Preserve critical habitat for birds and wildlife.

- Fight climate change.

- Protect biodiversity.

- Support farmers committed to conserving bird and wildlife habitat by farming sustainably.

Overview

- 100% organic: no use of chemical pesticides.

- Shade-grown coffee

- requires much of the natural forest canopy to remain intact through a combination of foliage cover, tree heights and overall biodiversity that protects high quality habitat for birds and other wildlife.

- Must maintain at least 15% of the native vegetation or a minimum canopy cover of 40% measured before pruning and during the rainy season when foliage is denser, and a minimum of 12 native species as shade in the coffee plantations, as well as comply with several infrastructural and management requirements.

- Certification requires 100% of product to meet standards (other certifications allow a portion of non-certified product or permit product dilution).

- Producers can earn more for their crops due to the gourmet market price premiums, and the timber and fruit trees on shade coffee farms provide farmers with additional income.

- Farms are certified by third-party inspectors using criteria established by the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center. The Center states that the criteria are based on years of research and are scientifically proven to provide bird habitat second only to undisturbed forest.

- farms must submit to re-certification every three years – roasters pay a small fee to be able to use the seal on their products.

- There are currently at least 5,100 Bird Friendly farmers in 11 countries growing 34 million pounds of coffee annually.

Problems

While the Bird-Friendly seal has farmers’ and community rights written into its overall goals, it is unclear if there are any defined and enforceable standards.

Fair Trade

Goals

- To guarantee that workers are paid living wages and have safe working conditions.

- To improve the lives of farmers and smallholders in developing countries who frequently lack alternative sources of income by promoting positive and long-term change through trade-based relationships that build self-sufficiency.

Overview

- Fair Trade pays producers an above-market “fair trade” price provided they meet specific labor, environmental, and production standards.

- The standard encompasses a wide variety of agricultural and handcrafted goods, including baskets, clothing, cotton, home and kitchen decor, jewellery, rice, soap, tea, toys, and wine.

- Fair Trade handcrafts have been sold since 1946. The first agricultural product to be certified fair trade, coffee, was in 1988.

- In 2021, FT worked with than 975,000 farmers and workers in 62 countries across Africa, Asia, Oceania, Latin America, and the Caribbean.

Standards

- Fair Trade requires producing organisations to comply with a set of minimum standards designed to support the sustainable development of small-scale producers and agricultural workers in the poorest countries in the world.

- These standards detail member farm size, electoral processes and democratic organization, contractual transparency and reporting, environmental standards etc.

- Fair Trade members buy products directly from producers and provide advance payment or pre-harvest financing. Unlike many commercial importers who often wait 60-90 days before paying producers, FTF members ensure pre-payment so that producers have sufficient funds to cover raw materials and basic needs during production.

- Fair Trade members also provide technical assistance and support such as market information, organizational development and training in financial management.

- Unlike conventional importers, FTF members establish long term relationships with their producers and help them adapt production to changing trends.

- Workers benefit from 100+ protections and quality of life assurances and receive regular training around health, safety and quality assurance.

Problems

The higher consumer price for Fair Trade coffee does not result in increased wages for farmers.

The quality of Fair Trade coffee is uneven.

Cost of Fair Trade certification: This costs coffee growers approximately $0.03 per pound of coffee. This doesn’t sound like much, but in some years it is greater than any smallholder/farmer profit from the sale of the coffee.

Fair trade certification does not bring economic benefits and equity to labourers and their children: A Harvard University study found the modest benefits generated from Fair Trade to be concentrated among the most skilled coffee growers. They find no positive impact on coffee laborers, no positive impact on children’s education, and negative impacts on the education of unskilled coffee workers’ children.

Poorer countries are not able to mobilise certification: Relatively little Fair Trade coffee originates from the poorest countries, like Ethiopia, and Tanzania.

Higher price for Fair Trade does not translate to higher quality coffee: This risks turning consumers away from FT produce, and further impeding its reach to mass markets, where it can truly make an important change to consumer habits.

Higher cost for Fair Trade means a lack of consumer access: The price premium on Fair Trade may make it prohibitively expensive for lower-income households to afford. This means that Fair Trade does not reach the mass market and instead remains as a token marketing gesture that helps to alleviate the guilt of middle class consumers.

Fair Trade engages with companies that are unethical:

Much like with the RSPO for palm oil, the Fair Trade certification does not guarantee that producer organizations will be able to sell all their certified goods under agreed conditions. There is a lack of transparency.

One primary factor is that it is large cooperatives that control the Fair Trade premium, rather than the farmers themselves. This means that rather than cutting out the middle man, and offering farmers a more direct compensation for their work, Fair Trade still facilitates a level of bureaucracy that supports an uneven distribution of revenue.

Rainforest Alliance

Goals

- Wildlife protection

- Climate-smart agriculture

- Fair treatment and good working conditions for workers

Overview

- Not required to be organic, but must implement the integrated pest management procedures, which have chemical pesticides only as a last resort and used in targeted, conscious methods.

- Promotes best practices for protecting standing forests, preventing the expansion of cropland into forests; fostering the health of trees, soils, and waterways; and protecting native forests.

- Promote responsible land management methods that increase carbon storage while avoiding deforestation.

- The 2020 programme prohibits deforestation and destruction of natural ecosystems such as wetlands and peatlands and sets 2014 as the baseline year for the conversion of natural ecosystem.

- Advances the rights of rural people.

- Certified farms and supply chain actors must have a system to evaluate and address child labour, forced labour, discrimination and workplace violence and harassment.

- Products do not have to contain 100% of ingredients meeting the standards in order to use the seal. **For the 2020 seal, all products – except herbal teas and palm oil – must contain at least 90% of the certified ingredient. Herbal teas must contain at least 40% of the certified ingredient(s) and palm oil products must contain at least 30% certified palm oil. Products that contain between 30 and 90 percent certified content can bear the seal with a qualifying statement that discloses the percentage of certified content.

- Farms are audited every 3 years.

Problems

A weak due diligence approach: With the newest 2020 criteria, Rainforest Alliance takes a ‘due diligence’ rather than prohibition approach. This approach means that absolutely nothing will be outlawed under the new criteria. Even a company found to use violence against forced laborers could continue to bear the logo if it had the right processes in place.

A “due diligence” approach has had success in specific cases. For example, it has helped address the problem of child labour in the cocoa industry, which is almost entirely made up of smallholders.

However now Rainforest Alliance is using this approach to address four of the most difficult areas – child labour, forced labour, discrimination and (sexual) harassment – without providing any evidence for its success in addressing the last three of these issues. Red lines can still be maintained even if a due diligence framework is adopted, but the RA have not explained why they have shunned this option even as a last resort.

Price volatility: failure to protect workers and farms from the volatility of prices on international markets. While Rainforest Alliance says that it is considering the issue, it has no plans to address the problem of price volatility through its certification.

2020 Weak Deforestation criteria: The new certification contains some requirements to protect forest areas, yet, it has no definition of what ‘forest’ means, without which the criteria are largely unenforceable.

It also conflates ‘forests’ and ‘other natural ecosystems’ in several of the new criteria, which is vague.

2020 workers rights criteria: These requirements are weaker or more vague than previous requirements. Including those on overtime, payment in kind, maternity leave, and preference for organic fertilisers

2020 child labor criteria: RA’s definition of child labour allows work from 14 years of age and light work from 12 years where these ages are set by the country’s national laws. It therefore sets a lower standard than the International Labour Organization’s (ILO’s), which only allows these ages where developing country exemptions apply.

Vital information missing: including how RA intends to enforce its standards, how it will determine timeframes for improvement criteria, what the rules will be about the use of its logo on products, or how it plans to conduct audits.

Recommendation: Cut coffee consumption as much as possible

Coffee production has detrimental impacts on forests, habitats, species biodiversity, greenhouse gas emissions and laborers.

Increasing demand for the product is fueling all of these crises. In order to alleviate this pressure, there must be an immense decrease in demand for coffee worldwide.

Consumers should choose to not purchase or to severely decrease their purchases of coffee and coffee-derived products.

If a person does want to purchase some coffee, it would seem most environmental and ethical to find a company that deals only with small-scale farmers, with whom they have a personal relationship, and avoid the huge, international corporations.

After investigation, it appears that the Smithsonian Bird-Friendly certification does a good job of protecting native forest and wildlife; however, it does not appear too guarantee workers’ rights. Consumers should also look for the FairTrade or similar certification that covers fair wages and labor practices.

It must be said, however, that neither certification is perfect. The best option would be to avoid coffee products entirely, as a consumer can never be 100% certain about the practices that took place along the entire production line.

How you can help

The Counterpunch: Consumer Solutions To Fight Extinction

Although the world is highly complex, every person can make a difference. That previous sentence almost sounds like a cliche right? Really it’s not. If every person on the planet made a few simple lifestyle changes, it would result in less demand on land and resources and soften the impact of deforestation on endangered species.…

Research: Boycotts Are Worthwhile and Effective

Despite sustained and vigorous attempts by corporates and industry certification schemes like RSPO, MSC and FSC to downplay the impact and effectiveness of consumer boycotts, it turns out that boycotts are impactful and drive social change. They force profit-first and greedy corporations to change their ways and do better. They also create a tangible sense…

Why join the #Boycott4Wildlife?

According to a 2021 survey by Nestle of 1001 people, 17% of millennial shoppers (25-45 years old) completely avoid palm oil in the supermarket. 25% said that they actively check to see if products contain palmoil. As a generation, we now have the opportunity to push our local communities and our children away from harmful…

Greenwashing Tactic #4: Fake Labels

Claiming a brand or commodity is green based on unreliable, ineffective endorsements or eco-labels such as the RSPO, Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) or FairTrade coffee and cocoa. Greenwashing: Fake Labels and fake certifications Ecolabels are designed to reassure consumers that they are purchasing green or sustainable products. In reality the environmental standards are no better…

References

- Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved from: https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=35189#null

- Vanzile, J. (2021, Aug 17) How to Grow and Care For Coffee Plant. The Spruce. Retrieved from: https://www.thespruce.com/grow-coffee-plants-1902614

- The Roaster Coffee Company (2020, May 11) Coffee 101: What Does a Coffee Plant Look Like? Retrieved from: https://theroasterie.com/blogs/news/coffee-101-what-does-a-coffee-plant-look-like

- Coffee Research Institute (2006) Arabica and Robusta Coffee Plant. Retrieved from: http://www.coffeeresearch.org/agriculture/coffeeplant.htm

- Institute for Scientific Health and information on Coffee. (2021) Where Coffee Grows. Retrieved from: https://www.coffeeandhealth.org/all-about-coffee/where-coffee-grows/

- Specialty Coffee Association of America. A Botanist’s Guide to Specialty Coffee. Retrieved from: http://scaa.org/index.php?goto=&page=resources&d=a-botanists-guide-to-specialty-coffee

- Myhrvold, N. (2021, Nov 16) Coffee. Britannica. Retrieved from: https://www.britannica.com/topic/coffee

- National Coffee Association of U.S.A., Inc. The History of Coffee. Retrieved from: https://www.ncausa.org/about-coffee/history-of-coffee

- Durovic , J. History Of Coffee: Where Did Coffee Originate And How Was It Discovered? Retrieved from: https://www.homegrounds.co/history-of-coffee/

- Bernard, K. (2020, Aug 6) The Top Coffee-Consuming Countries. Society. Retrieved from: https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/top-10-coffee-consuming-nations.html

- World Population Review. Coffee Consumption by Country 2021. Retrieved from: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/coffee-consumption-by-country

- Workman, D. (2021, June) Coffee Imports by Country. Retrieved from: https://www.worldstopexports.com/coffee-imports-by-country/

- Statistica. Leading coffee importing countries worldwide in 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1096400/main-import-countries-for-coffee-worldwide/

- United States Department of Agriculture – Foreign Agricultural Service (2021, Dec) Coffee: World Markets and Trade. Retrieved from: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/circulars/coffee.pdf

- Coffee production by exporting countries (PDF). International Coffee Organization. February 2021. https://www.ico.org/prices/po-production.pdf

- Deshmukh, A. (2021, Oct 1) The World’s Top Coffee Producing Countries. Visual Capitalist. Retrieved from: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/worlds-top-coffee-producing-countries/

- United States Department of Agriculture. “Coffee: World Markets and Trade., https://downloads.usda.library.cornell.edu/usda-esmis/files/m900nt40f/sq87c919h/8w32rm91m/coffee.pdf.” Accessed Dec. 20, 2021.

- Shalene Jha, Christopher M. Bacon, Stacy M. Philpott, V. Ernesto Méndez, Peter Läderach, Robert A. Rice, Shade Coffee: Update on a Disappearing Refuge for Biodiversity, BioScience, Volume 64, Issue 5, May 2014, Pages 416–428, https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biu038

- Retrieved from: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/sustainable-coffee_n_5175192

- Satran, J. (2014, Apr 29) The Coffee Industry Is Worse Than Ever For The Environment. Retrieved from: https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2019/03/12/shade-grown-coffee-sustainable/

- International Research Institute for Climate and Society. (2019, Mar 12) Shade-Grown Coffee Helps Ecosystems and Farmers. Columbia Climate School. Retrieved from: https://nationalzoo.si.edu/migratory-birds/ecological-benefits-shade-grown-coffee

- The University of Texas at Austin. (2014, Apr 16) Shade Grown Coffee Shrinking as a Proportion of Global Coffee Production. UT News. Retrieved from: https://news.utexas.edu/2014/04/16/global-production-of-shade-grown-coffee-shrinking/

- Person, L. (2008). Ethics and Environment in the Coffee Sector – Linking CSR to the Consumer’s Power in the Context of Sustainable Development.

- Food Empowerment Project. (2021) BITTER BREW: THE STIRRING REALITY OF COFFEE. Retrieved from: https://foodispower.org/our-food-choices/coffee/

- Scott, M. (2015, June 19) Climate & Coffee. Retrieved from: https://www.climate.gov/news-features/climate-and/climate-coffee

- Coffee Chemistry. (2016, Mar 19) Growing Conditions for Coffee. Retrieved from: https://www.coffeechemistry.com/growing-conditions-for-coffee

- Bibium. What is the coffee bean belt? Retrieved from: https://bibium.co.uk/bean-belt-infographic/

- The Ohio State University. (2015, Nov) COFFEE – FROM SHRUB TO MUG! Retrieved from: https://u.osu.edu/ryanrichardscoffeecommoditychain/sample-page/

- Blacksell, G. (2011, Oct 4) How green is your coffee? Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2011/oct/04/green-coffee

- Treanor, N.B. and Saunders, J. TACKLING (ILLEGAL) DEFORESTATION IN COFFEE SUPPLY CHAINS: WHAT IMPACT CAN DEMAND-SIDE REGULATIONS HAVE? Retrieved from: https://www.forest-trends.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/10-things-to-know-about-coffee-production.pdf

- BBC (2021, Nov 15) Brazil: Amazon sees worst deforestation levels in 15 years. Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-59341770

- Summers, C. (2014, Jan 25) How Vietnam became a coffee giant. Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-25811724

- International Coffee Organization. (2019, Mar 4) Country Coffee Profile: Vietnam. Retrieved from: http://www.ico.org/documents/cy2018-19/icc-124-9e-profile-vietnam.pdf

- Global Forest Watch. Retrieved from: https://onetreeplanted.org/pages/global-forest-watch?utm_source=google-search&utm_medium=pdmr&utm_campaign={campaign}&utm_term=global%20forest&gclid=CjwKCAiAiKuOBhBQEiwAId_sKzNT7CEGudV5sOUk9Yx6IWdS9YH03y3qpRdp9POuyluR_UrQvROmiRoCI2gQAvD_BwE

- Dutch Green Business (2021, Mar 14) Countries With the Highest Deforestation Rates in the World. Retrieved from: https://www.dgb.earth/blog/countries-highest-deforestation-rates

- World Resources Institute. Sustaining Forests for People and Planet. Retrieved from: https://www.wri.org/forests

- FAO and UNEP. 2020. The State of the World’s Forests 2020. Forests, biodiversity and people. Rome.

- Ritchie, H. and Roser, M. (2021). “Forests and Deforestation”. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: https://ourworldindata.org/forests-and-deforestation

- Hosonuma, N., Herold, M., De Sy, V., De Fries, R. S., Brockhaus, M., Verchot, L., … & Romijn, E. (2012). An assessment of deforestation and forest degradation drivers in developing countries. Environmental Research Letters, 7(4), 044009.

- Crowther, T. W., Glick, H. B., Covey, K. R., Bettigole, C., Maynard, D. S., Thomas, S. M., … & Tuanmu, M. N. (2015). Mapping tree density at a global scale. Nature, 525(7568), 201-205.

- Pendrill, F., Persson, U. M., Godar, J., & Kastner, T. (2019). Deforestation displaced: trade in forest-risk commodities and the prospects for a global forest transition. Environmental Research Letters, 14(5), 055003.

- BBC Reality Check Team. (2021, Nov 19) Deforestation: Which countries are still cutting down trees? Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.com/news/59136545

- Butler, R.A. (2019 Apr 1) Deforestation. Retrieved from: https://rainforests.mongabay.com/08-deforestation.html

- Philpott, S.M.; Arendt, W.J.; Armbrecht, I.; Bichier, P.; Diestch, T.V.; Gordon, C.; Greenberg, R.; Perfecto, I.; Reynoso-Santos, R.; Soto-Pinto, L.; Tejeda-Cruz, C.; Williams-Linera, G.; Valenzuela, J.; Zolotoff, J.M. 2008. Biodiversity loss in Latin America coffee landscapes: review of the evidence on ants, birds, and trees. Conservation Biology. 22(5):1093-1105. https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/7979/1ACEABF2-5CEC-4140-BB60-8DEA504ED8B0.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Wertheimer, C. (2019, Apr 29) How can coffee plantations be more bird-friendly? National Geographic. Retrieved from: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/shade-trees-coffee-plantations-effect-bird-biodiversity

- Valerie E. Peters, Tomás A. Carlo, Marco A. R. Mello, Robert A. Rice, Doug W. Tallamy, S. Amanda Caudill, Theodore H. Fleming, Using Plant–Animal Interactions to Inform Tree Selection in Tree-Based Agroecosystems for Enhanced Biodiversity, BioScience, Volume 66, Issue 12, December 2016, Pages 1046–1056, https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biw140

- Tscharntke,T.; Milder, J.C.; Schroth, G.; Clough, Y.; DeClerck, F.; Waldron, A.; Rice, RR.; Ghazoul, J. (2014). Conserving Biodiversity Through Certification of Tropical Agroforestry Crops at Local and Landscape Scales. Society for Conservation Biology – Conservation Letters. Vol 8, Issue 1. https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/conl.12110

- Smithsonian’s National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute. (2021) Meet the Birds Supported by Bird Friendly Coffee Farms. Retrieved from: https://nationalzoo.si.edu/migratory-birds/meet-birds-supported-bird-friendly-coffee-farms

- The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (2021) Golden-winged Warbler: Conservation Strategy and Resources. Retrieved from: https://www.birds.cornell.edu/home/golden-winged-warbler-conservation-strategy-and-resources/

- Nelson, B. (2018, January 25). The World’s Most Expensive Coffee Is Actually Made with Animal Poop | Reader’s Digest. Retrieved from: https://www.rd.com/food/fun/expensive-coffee-animal-poop/ (2/2/18)

- Bale, R. (2016, April 29). The Disturbing Secret Behind the World’s Most Expensive Coffee. https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/04/160429-kopi-luwak-captive-civet-coffee-Indonesia/ (2/2/18)

- Lynn, G., Rogers, C., “Civet cat coffee’s animal cruelty secrets,” BBC News, September 13, 2013. Retrieved from: http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-london-24034029 (2/2/18)

- Associated Press, “Coffee from an elephant’s gut fills a $50 cup,” USA Today, December 7, 2012. Retrieved from: https://www.usatoday.com/story/tech/sciencefair/2012/12/07/coffee-elephants-dung/1753385/ (2/2/18)

- Majendie, Adam. “World’s Priciest Coffee is Hand-Picked from Elephant Dung,” Bloomberg, January 26, 2017. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/photo-essays/2017-01-27/world-s-priciest-coffee-is-hand-picked-from-elephant-dung ( 5/14/18)

- Butler, R.A. (2020, Aug 14) RAINFOREST INFORMATION. Retrieved from: https://rainforests.mongabay.com/

- Butler, R.A. (2019, April 1) Consequences of Deforestation. chttps://rainforests.mongabay.com/09-consequences-of-deforestation.html

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2021, Oct 26) Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions Data. Retrieved from: https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-data

- Rainforest Alliance. (2018, Aug 12) What is the Relationship Between Deforestation And Climate Change? Retrieved from: https://www.rainforest-alliance.org/insights/what-is-the-relationship-between-deforestation-and-climate-change/

- Union of Concerned Scientists. (2021, Nov 10) Tropical Deforestation and Global Warming. Retrieved from: https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/tropical-deforestation-and-global-warming

- Rice, R. (2003). Coffee Production in a Time of Crisis: Social and Environmental Connections. SAIS Review XXIII(1). 221-245. http://cftn.ca/sites/default/files/AcademicLiterature/coffee%20production.pdf

- No Child for Sale. (2016, April). http://nochildforsale.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Coffee_Infographic.pdf

- Nestlé admits slave labour risk on Brazil coffee plantations. The Guardian. (2016, March 2). https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/mar/02/nestle-admits-slave-labour-risk-on-brazil-coffee-plantations

- Kruger, D. I. (2007). Coffee Production Effects on Child Labor and Schooling in Rural Brazil. Journal of Development Economics, 82(2), 448-463.

- Smithsonian’s National Zoo & Conservation biology Institute. About Bird Friendly Coffee. Retrieved from: https://nationalzoo.si.edu/migratory-birds/about-bird-friendly-coffee

- Smithsonian’s National Zoo & Conservation biology Institute. Bird Friendly Farm Criteria. Retrieved from: https://nationalzoo.si.edu/migratory-birds/bird-friendly-farm-criteria

- Rainforest Alliance. (2020, Oct 28) What Does “Rainforest Alliance Certified” Mean? Retrieved from: https://www.rainforest-alliance.org/insights/what-does-rainforest-alliance-certified-mean/

- Rainforest Alliance. (2021, Jan 28) 2020 Sustainable Agriculture Standard: Farm Requirements. Retrieved from: https://www.rainforest-alliance.org/resource-item/2020-sustainable-agriculture-standard-farm-requirements/

- Rainforest Alliance. 2020 Certification Program. Retrieved from: https://www.rainforest-alliance.org/tag/2020-certification-program/

- Carlile, C. (2019, Apr 29) Questions about Rainforest Alliance. Retrieved from: https://www.ethicalconsumer.org/food-drink/questions-about-rainforest-alliance

- GreenPeace International. (2021, March 10) Destruction: Certified. Retrieved from: https://www.greenpeace.org/international/publication/46812/destruction-certified/

- Lindgren, K. (2013, March 16) Rainforest Alliance Is Not Fair Trade. Retrieved from: https://fairworldproject.org/rainforest-alliance-is-not-fair-trade/

- GrrlScientist. (2021, March 6) Bird-Friendly Coffees Really Are For The Birds. Retrieved from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/grrlscientist/2021/03/06/bird-friendly-coffees-really-are-for-the-birds/?sh=30e41d086663

- Allen, J. Is Your Coffee Bird Friendly? Retrieved from: https://www.sierraclub.org/atlantic/iroquois/your-coffee-bird-friendly

- Craves, J. (2019, Feb 19) The true cost of coffee. Retrieved from: https://www.birdwatchingdaily.com/news/conservation/the-true-cost-of-coffee/

- Nemo, L. (2021, March 24) What The Shade-Grown Label Means on Your Coffee. Retrieved from: https://www.discovermagazine.com/environment/what-the-shade-grown-label-means-on-your-coffee

- González-Prieto, A. 2018. Conservation of Nearctic Neotropical migrants: the coffee connection revisited. Avian Conservation and Ecology 13(1):19.

https://doi.org/10.5751/ACE-01223-130119

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Discover more from Palm Oil Detectives

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

4 thoughts on “The World’s Most Loved Cup: A Social, Ethical & Environmental History of Coffee by Aviary Doert”