Want to hear something trippy? Unlike other aspects of an object such as its size or mass, colour is not an inherent property. Perceiving colour is a function of an organism’s sensory system. In other words, colour is a construct of the mind. But whose minds? Aside from various human experiences of colour, other-than-human eyes perceive colour in radically different ways.

Seeing the world through the eyes of #shrimp 🍤#bees 🐝🪲 #apes 🦧🦍 #dogs 🐶🐕 is a deep-dive into wonder. It generates a humble understanding of diverse ways of seeing the world #communication #behaviour #vision #animals #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2021/03/17/inside-the-colourful-world-of-animal-vision/

The eye’s retina contains specialised cells called photoreceptors, which convert light that bounces off objects into signals that the brain processes into visual images. Two types of photoreceptors are rods and cones.

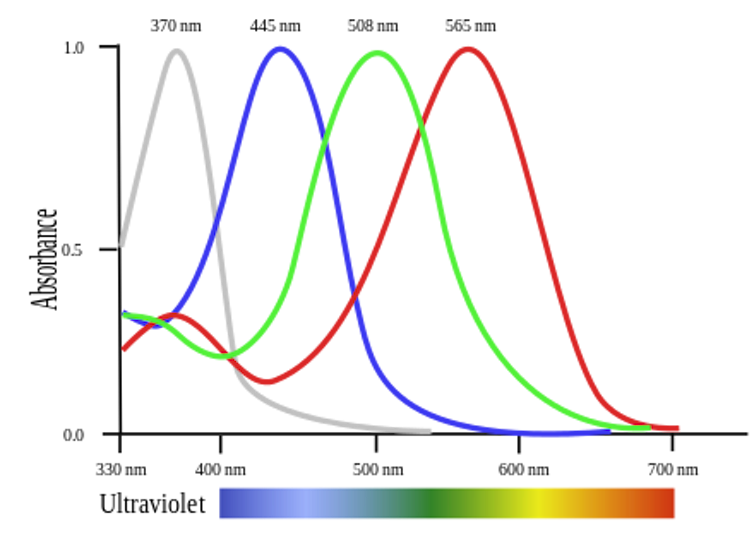

In humans, there are three types of cone cell that are responsible for the early stages of colour vision. Each type of cone cell is maximally absorbent in a different part of the spectrum – short, medium and long wavelengths of light. These are typically named blue, green and red cones, respectively, to describe how humans perceive light at each cone’s peak absorbency.

When light hits the eye, the cones are stimulated differentially according to their type, and the relative excitation of each type underlies colour sensations. In a process known as colour opponency, the outputs are then compared against each other in various permutations. This information is then sent to and interpreted by the brain, which provides the final sensation of colour.

How do other animals see colour?

Animals vary in the number and sensitivity of cones present, so visual processing can result in very different colour sensations, even before differences in brain processing are taken into account.

Most mammals are dichromatic – they have only two cone types (blue and green sensitive). Humans have three types of interacting cones and so are trichromatic, although there is at least one documented case of a female having four cones.

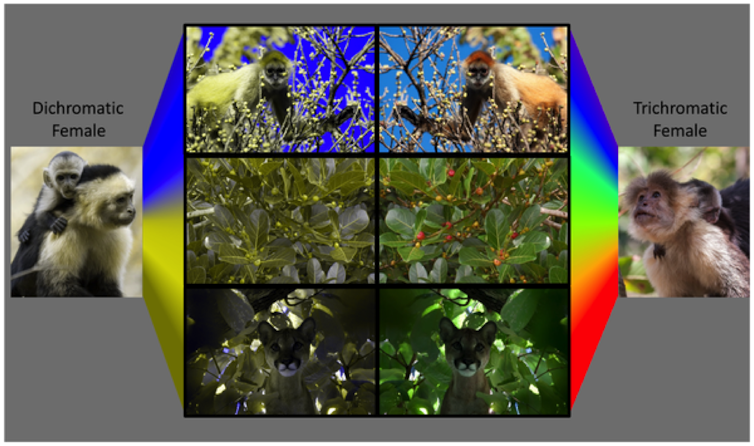

Apes and Old World monkeys also have trichromatic vision, but New World monkeys have variable colour vision that is also sex-linked, meaning that males and females of the same species can have different numbers of cone type. Generally, females are trichromats whereas males are dichromats as they lack the photoreceptor that is sensitive to red wavelengths of light.

In several species of New World monkeys, such as marmosets and tamarins, all males are dichromatic but females may be either dichromatic or trichromatic. Trichromacy may offer a foraging advantage by enabling green and red food items to be easily distinguished, but may also be useful in signalling amongst individuals of the same species, whereas dichromacy may be advantageous when foraging for camouflaged food or in low light levels.

Bees are also trichromatic, but they can see ultraviolet (UV) light as they have a UV sensitive receptor, as well as blue and green sensitive receptors. In contrast, most birds, fish, and some insects and reptiles are tetrachromatic, having four (but sometimes even five or more) types of cone cell. In many cases in tetrachromats, the fourth photoreceptor allows the animal to perceive UV light.

Despite not having a specific UV receptor, it was recently discovered that reindeer in the Arctic Circle see UV light. While the mechanism of this ability is still under investigation, it is thought that UV vision evolved due to the UV rich snowy conditions that the reindeer live in.

Lichens, which are a major source of food for reindeer, absorb UV light, as does urine – a good indicator of the presence of predators or potential mates. These appear black against the UV reflecting snow and are likely easier to see.

Do more photoreceptors result in better colour vision?

Theory predicts that a visual system comprised of around five photoreceptor types is plenty for encoding colours of the visual spectrum in day-to-day life.

The mantis shrimp (Haptosquilla trispinosa) by far exceeds this, with 12 photoreceptors. It was thought that the 12 types of photoreceptor in this marine crustacean allowed them to see a spectacular array of colours that we, as humans, could not imagine.

A recent study examining this hypothesis tested the limits of the mantis shrimp’s ability to discriminate between two colours. If more photoreceptors enable heightened colour perception, then the shrimp should be excellent at distinguishing between similar colours. Surprisingly, however, the mantis shrimp performed worse than humans.

The shrimp seem to have evolved a novel way of encoding colour, as the photoreceptor outputs do not undergo any opponent processing. The outputs appear to be sent directly to the brain where they may be compared to a “mental template” of colours. This type of vision may be advantageous as light requires less processing in the eye and is therefore likely to be more rapid. However, nothing is yet known about how the brain processes these inputs.

In truth, we can probably never know how a shrimp, or any kind of animal, perceives colour. Not only is it difficult for us to imagine colour vision more with more dimensions than our own, but we also need to account for how the brain interprets such information. That being said, there is still much left to learn about the colourful world of animal vision.

Laura Kelley, Research Fellow, University of Cambridge. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Discover more from Palm Oil Detectives

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.