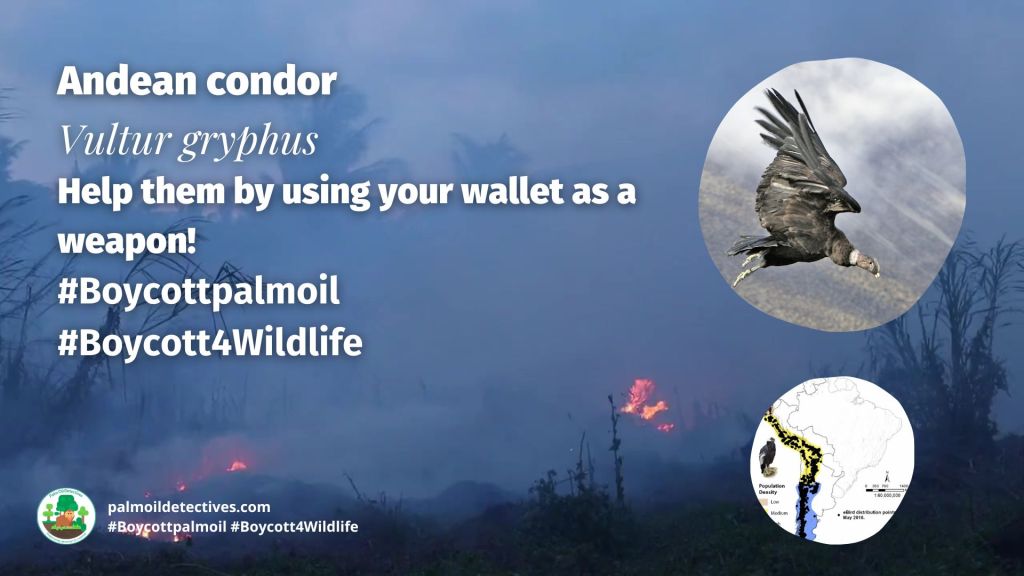

Andean condor Vultur gryphus

Vulnerable

Resident: Argentina, Bolivia, Chile; Colombia, Ecuador; Peru, Brazil, Paraguay.

Possibly Extinct and Reintroduced: Venezuela, Bolivia

The Andean condor Vultur gryphus is one of the largest flying #birds in the world and arguably the most majestic, with a wingspan of up to 3.3 metres and a body weight of up to 15 kilograms. These amazing birds are able to soar for up to five hours and cruise for over 100 kilometres using only the wind currents, not flapping. These vultures are primarily scavengers, feeding on carrion from large carcasses such as deer, cattle, and marine mammals. With a striking black plumage and distinct white ruff around their necks, they are iconic symbols of the #Andes mountains. Despite their impressive size and strength, Andean #condors are classified as #Vulnerable from human-related threats including habitat loss for #palmoil, #soy and #meat #deforestation. Farmers persecute these beautiful birds putting poison into animal carcasses. Their slow reproductive rate makes their survival even more challenging. These birds are critical for ecosystems, disposing carrion. Thus they prevent the spread of diseases. Help them to survive by simply changing your diet and buying habits. #BoycottMeat and be #vegan #Boycott4Wildlife

Andean #Condors of #SouthAmerica 🦃 😻 are the largest flying #birds in 🌍 have a wingspan of 3.3. mtrs, they soar 100’s of km on the wind. They’re endangered due to intensive #agriculture. Help them survive, be #vegan #Boycott4Wildlife 🍉🥒 @palmoildetect https://wp.me/pcFhgU-8S0

Soaring flying #birds of #Peru #Ecuador #Colombia and #Brazil, Andean #Condors are #vulnerable from #agriculture and ranchers poisoning them with #pesticide. Help these magnificent birds to survive! Be #vegan 🥕🥦 and #Boycott4Wildlife 🦅💚 @palmoildetect https://wp.me/pcFhgU-8S0

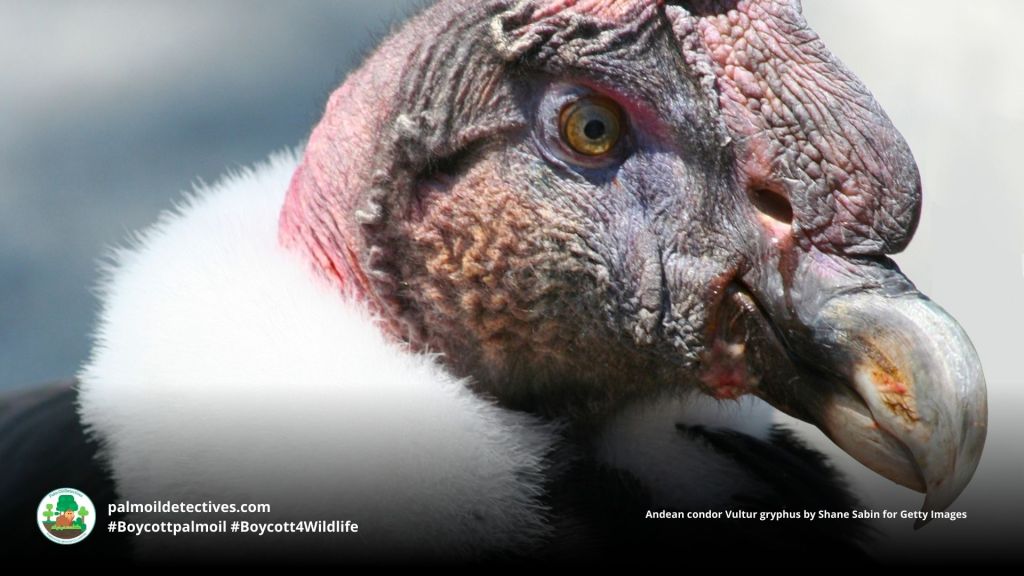

Appearance & Behaviour

The Andean condor is a strangely beautiful and ecologically important bird. Their regal standing pose is an impressive height of 1.2 metres. With their wingspan reaching up to 3.3 metres. This makes Andean Condors the largest flying birds in the world by weight and wingspan combined. One study found that a condor was able to glide for over 100 kilometres without flapping their wings. They are built for soaring, using their large wings and air currents to glide effortlessly through the skies, often travelling more than 200 kilometres in a single day in search of food.

Adults are almost entirely black, except for a striking white frill around their necks and large white patches on their wings, which are only visible after their first moult.

The condor’s bald head and neck are red to blackish-red, and this colour can change rapidly depending on their emotional state. Males boast a dark red comb on their heads and a wattle on their necks, which are absent in females. Interestingly, males are larger than females, an unusual trait among birds of prey.

Andean Condors are social birds and form strong social hierarchies within their groups. Dominant males typically occupy the highest rank. Alpha males use body language, competitive play and vocalisations to establish their dominance. In flight, their long wings and bent-up primary feathers give them a unique silhouette, allowing them to soar for hours with minimal wing flapping.

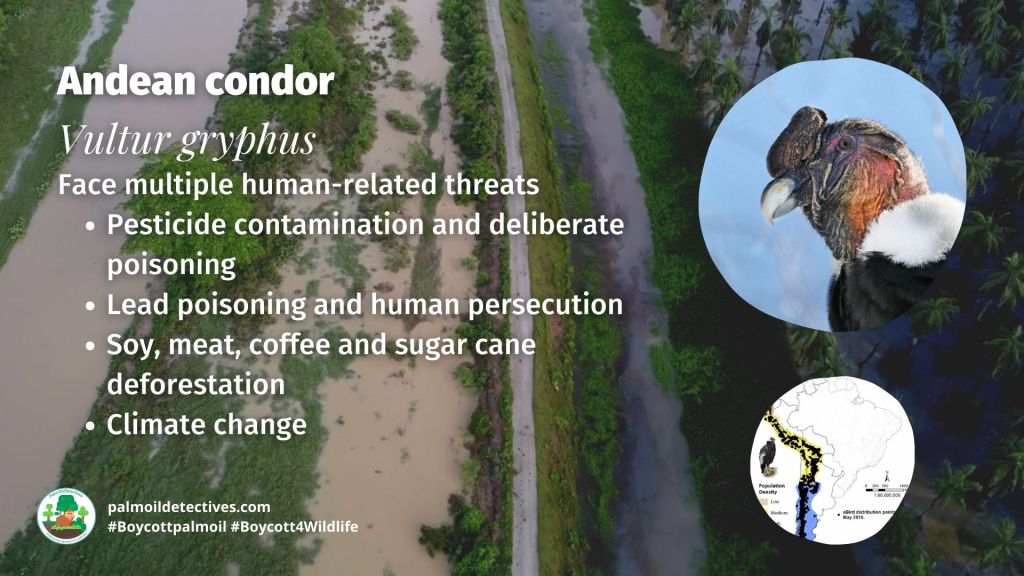

Threats

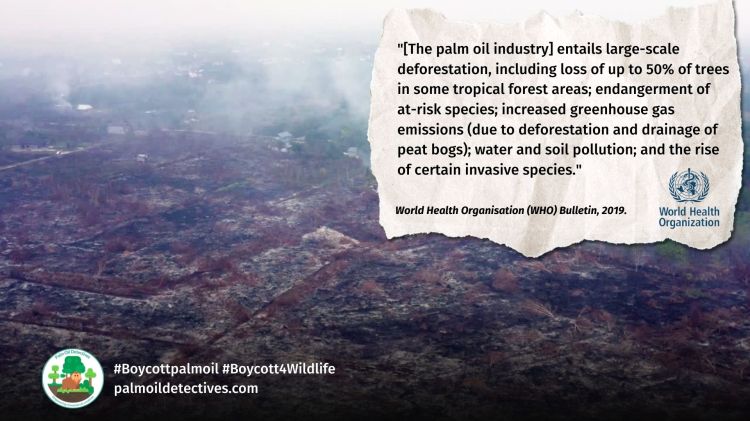

Pesticide contamination

Widespread use of pesticides in agricultural areas is one of the most critical threats to Andean condors. When condors consume carcasses contaminated by these chemicals, they suffer from severe poisoning, which affects their health and reproductive success. This long-term exposure has a cumulative negative impact on condor populations .

Human-wildlife conflict

In rural areas, particularly in Bolivia, poisoned bait intended for predators like pumas has unintentionally killed condors. In 2021, 34 condors were found dead after consuming poisoned bait meant for other animals. This incident led the town of Laderas Norte to declare itself a protected reserve for condors, though the vast range of the species limits the effectiveness of localised protection .

Lead poisoning

Andean Condors are also exposed to lead poisoning when they consume carcasses shot with lead-based ammunition. This toxin can cause severe damage to their nervous systems and further reduce their already declining population .

Agricultural expansion

The expansion of agriculture for soy, meat, coffee and sugar cane is destroying the condors’ natural habitat. This destruction reduces their available foraging grounds and nesting areas. This also increases the likelihood of encounters with humans, further elevating the risk of persecution.

Persecution by farmers

Andean condors are often wrongly accused of attacking livestock, which leads to persecution through direct hunting or poisoning. Despite their preference for scavenging, these birds are sometimes seen as a threat by farmers .

Each of these threats compounds the challenges faced by the Andean condor, placing them at significant risk of further population decline. A combination of strong and urgent protection and better educational awareness of them as a species is necessary. As a consumer you can boycott meat and soy and be vegan (meat and soy are main sources of agricultural expansion throughout their range).

Habitat

The Andean condor can be found across South America, primarily in the Andes mountain range. Their range includes countries such as Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. They also inhabit coastal regions and, occasionally, lowland deserts and grasslands. Though rare, condors have been reported in Brazil, Venezuela, and Paraguay, but populations in these countries are thought to be vagrant. They are most often found in open grasslands and alpine areas, where they can spot carrion from the air.

Diet

Andean condors are obligate scavengers, meaning their diet primarily consists of carrion. They prefer large carcasses of deer, cattle, or marine mammals, and they have been known to feed on wild animals such as guanacos, llamas, and rheas. Along the coast, they often consume the beached carcasses of whales and sea lions. Occasionally, they may raid smaller birds’ nests to eat eggs or even hunt small mammals like rabbits and rodents, though this is rare. Despite their size, Andean condors do not possess strong talons for capturing prey and rely on their large beaks to tear into the tough hides of deceased animals.

Mating and breeding

Andean condors are monogamous and form lifelong pairs. During courtship, males display their dominance by inflating the skin around their necks, which changes from dull red to a brilliant yellow. They also engage in a series of elaborate displays, including wing spreading and vocalisations. Females lay one to two eggs, which hatch after an incubation period of 54 to 58 days. Both parents share in the incubation duties. Once the chick hatches, they remain with their parents for up to two years, learning to soar and hunt before becoming fully independent. Condors breed every two years, and due to their low reproductive rate, their populations are slow to recover from declines.

Support Andean Condor by going vegan and boycotting palm oil in the supermarket, it’s the #Boycott4Wildlife

Efforts to protect the Andean condor have gained momentum across South America. Numerous reintroduction programs, using captive-bred individuals, are in place in countries like Argentina, Colombia, and Chile. These programs are crucial, as the species faces threats from habitat loss, secondary poisoning, and direct persecution. Condors are often mistakenly targeted by farmers who perceive them as a threat to livestock.

In a significant and symbolic act of protection, the town of Laderas Norte in southern Bolivia became a reserve for Andean condors in 2021. After 34 condors were unintentionally killed by poisoned bait meant for pumas, the town passed a municipal law turning itself into a protected area for these birds. The Quebracho and Condor Natural Reserve, covering 3,296 hectares (8,145 acres), may not be vast enough to fully secure the condors’ daily roaming needs, but it is a powerful gesture showing community commitment to protecting this majestic species. This reserve also protects a key stand of white quebracho trees, adding further ecological value to the area.

Further Information

BirdLife International. (2020). Vultur gryphus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T22697641A181325230. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22697641A181325230.en

Mongabay. (2023, December). Top stories of change from Latin America in 2023. Mongabay. https://news.mongabay.com/2023/12/top-stories-of-change-from-latin-america-in-2023/

Piña, C. I., Pacheco, R. E., Jacome, L., Borghi, C. E., & Pavez, E. F. (2020). Pesticides: The most threat to the conservation of the Andean condor (Vultur gryphus). Biological Conservation, 242, 108418. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108418

Wikipedia contributors. (2023, September 11). Andean condor. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andean_condor

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

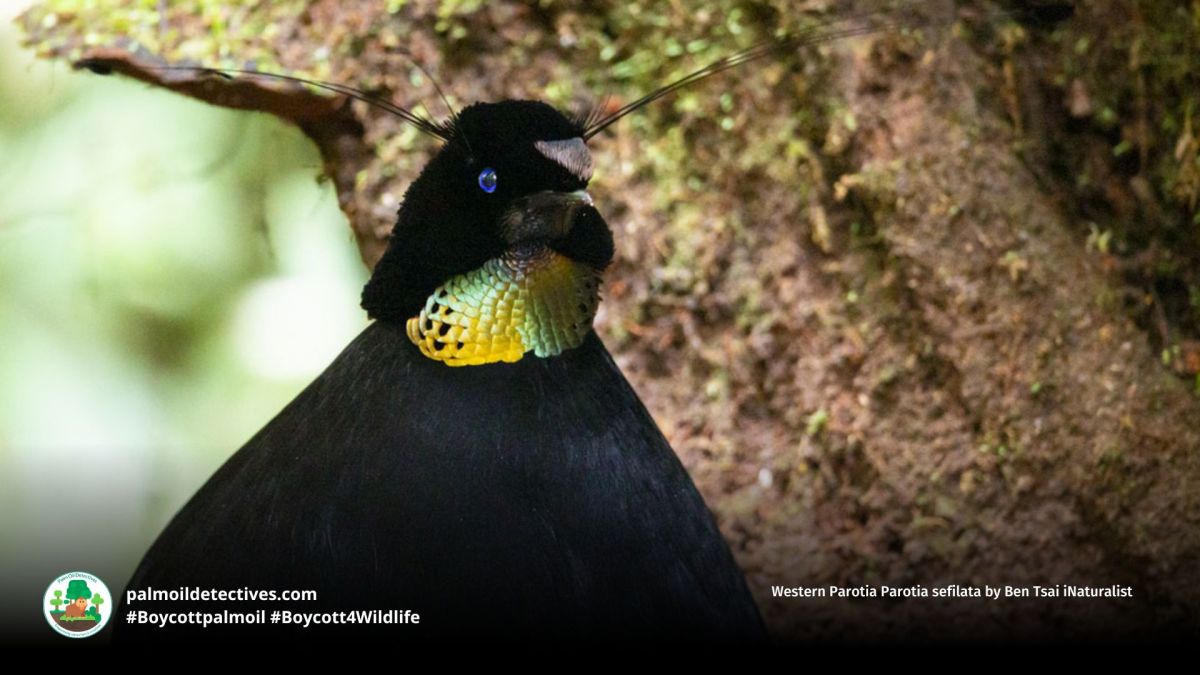

Learn about other animals endangered by palm oil and other agriculture

Learn about “sustainable” palm oil greenwashing

Read more about RSPO greenwashing

A 2019 World Health Organisation (WHO) report into the palm oil industry and RSPO finds extensive greenwashing of palm oil deforestation and the murder of endangered animals (i.e. biodiversity loss)

Discover more from Palm Oil Detectives

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Andean condor Vultur gryphus”