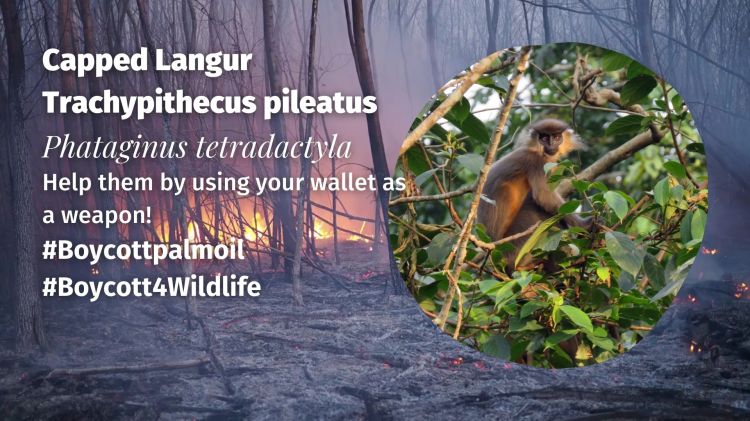

Capped Langur Trachypithecus pileatus

IUCN Red List Status: Vulnerable

Location: India, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Myanmar

This species inhabits subtropical and tropical dry forests, primarily in the foothills and highlands south of the Brahmaputra River and across fragmented patches in northeastern South Asia.

The capped #langur (Trachypithecus pileatus) is a graceful and beautiful leaf #monkey found across northeastern #India, #Bhutan, #Bangladesh, and #Myanmar. Sadly, they are listed as #Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List due to rapid population declines from #deforestation, logging, agriculture, and the devastating impacts of #palmoil plantations. Once widespread, their numbers have nearly halved in some regions like Assam due to the accelerating loss of native forest cover. Directly threatened by palm oil and monoculture expansion, this species is now confined to small, isolated forest fragments. Take action every time you shop and #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife

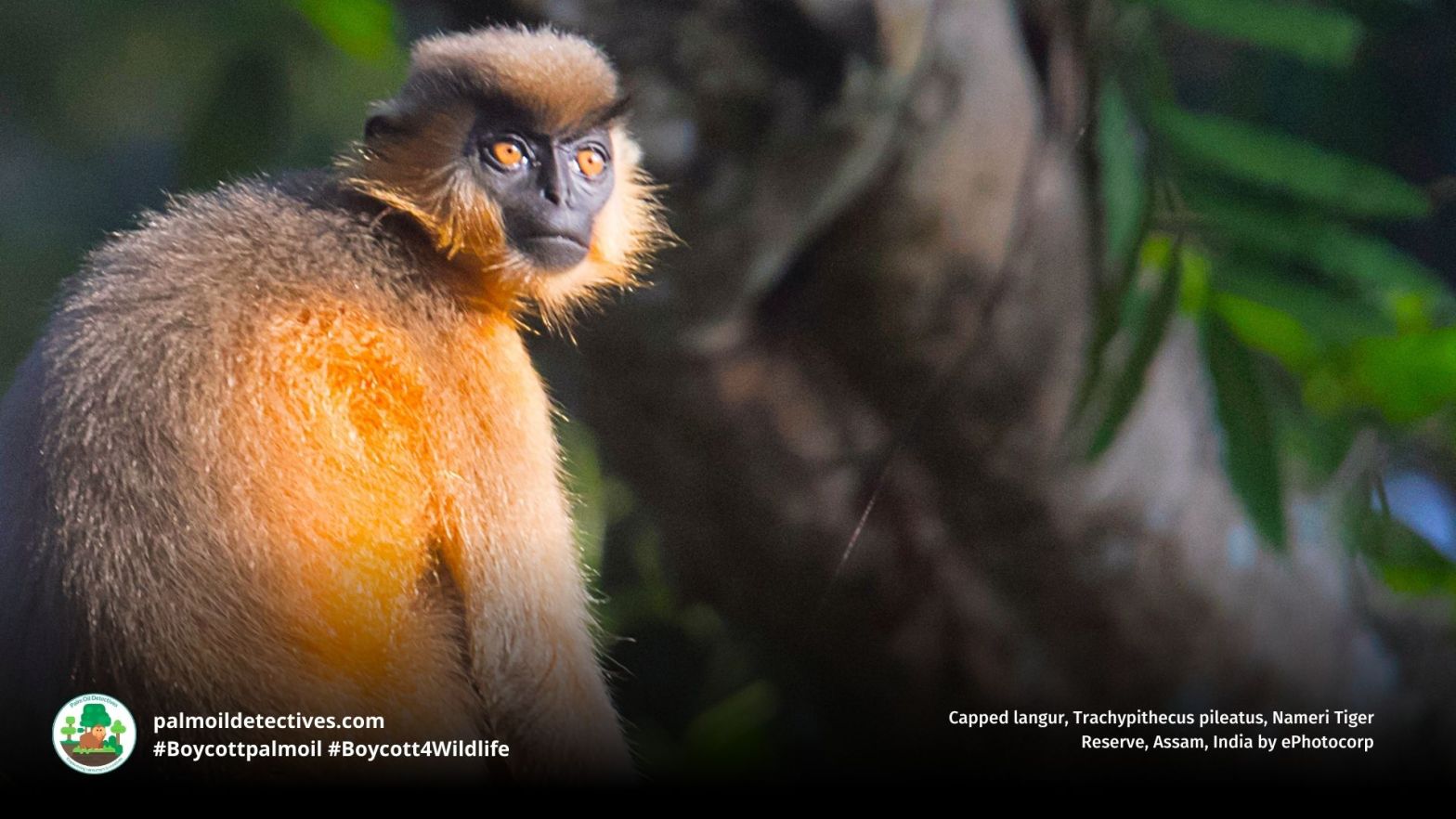

In the forests of #Bangladesh 🇧🇩 and northern #India 🇮🇳 lives a remarkable #primate with soulful hazel eyes 🐵🐒 on the verge of #extinction from #palmoil #deforestation. Help the Capped #Langur and #Boycottpalmoil 🌴🔥🚫 #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2026/01/11/capped-langur-trachypithecus-pileatus/

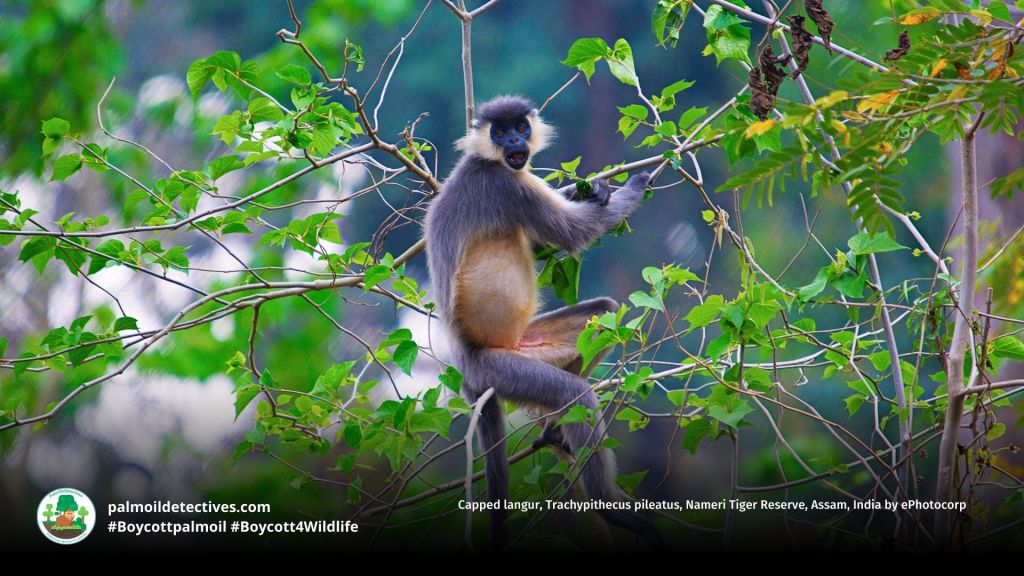

The intelligent and social Capped #Langur 🙉🐒🐵 is under pressure from #palmoil #deforestation and hunting in #India 🇮🇳 Troops are interbreeding with Phayre’s #langurs to survive. Fight for them and #Boycottpalmoil 🌴☠️❌ #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2026/01/11/capped-langur-trachypithecus-pileatus/

Appearance & Behaviour

With their black-tufted crown, pale fur, and soulful eyes, capped langurs are among the most visually distinctive primates in the Eastern Himalayas. Their fur ranges from silver-grey to golden orange, with darker limbs and a black cap that gives them their name. They move gracefully through the canopy, rarely descending to the forest floor except for play or social grooming.

Capped langurs live in unimale, multifemale groups with sizes ranging from 8 to 15 individuals. They spend most of their time feeding (up to 67%) or resting (up to 40%), engaging in complex social grooming and vocal communication. Daily movements range from 320–800 metres across fragmented habitats of 21–64 hectares. Grooming is an important social activity, with females often taking turns in allomothering behaviour.

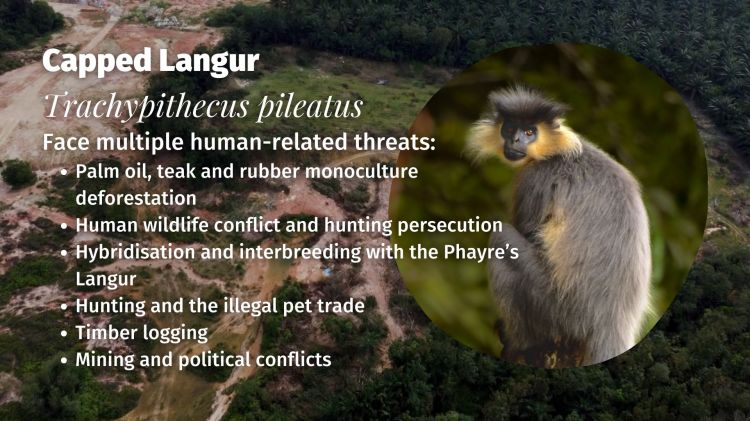

Threats

Palm oil, teak and rubber monoculture plantations

The spread of oil palm and other monoculture crops such as teak and rubber is destroying the capped langur’s native forests at an alarming rate. These industrial plantations eliminate the diverse tree species that capped langurs rely on for food and shelter, leaving them with little to survive on. Once a landscape is cleared and replaced with palm oil or other single crops, it becomes a green desert devoid of biodiversity, pushing the species closer to extinction. In regions like Assam and Bangladesh, palm oil is a major driver of habitat fragmentation and degradation, especially in forest corridors that once connected populations.

Timber deforestation

Widespread illegal logging, often fuelled by demand for timber and firewood, is rapidly eroding the capped langur’s habitat. Fruiting and lodging trees that are vital to their survival are cut down, leaving forests patchy and disconnected. As their home ranges shrink, capped langur groups are forced into smaller fragments, increasing their vulnerability to predators, food shortages, and inbreeding. In some areas, this pressure has led to local extinctions or the collapse of entire populations.

Slash-and-burn agriculture

Slash-and-burn agriculture destroys habitat for capped langurs and often brings them into closer contact with human settlements, increasing conflict and risk of hunting or roadkill. Forest recovery from this can take decades—time the capped langur simply doesn’t have.

Hunting and the illegal pet trade

Capped langurs are hunted for their meat, pelts, and for sale in the illegal pet trade. In many tribal and rural areas of Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, and Manipur, they are still targeted despite legal protections. Their pelts are used to make traditional knife sheaths, and infants are often captured after killing their mothers, then sold as pets. This exploitation causes severe suffering and has a devastating impact on group structures, leading to long-term population decline.

Roads cut into rainforests for mines and tea plantations

As forests are cut into smaller patches for roads, mining, tea plantations, and settlements, capped langur populations become increasingly isolated. Small, disconnected populations face higher risks of inbreeding, loss of genetic diversity, and eventual extinction. In some regions, such as Tinsukia and Sonitpur, populations have already disappeared due to this fragmentation. The collapse of corridors also disrupts daily movement, feeding patterns, and access to mates—placing enormous stress on surviving individuals.

Hybridisation with other species

Due to the rapid degradation of natural habitats, capped langurs are increasingly forming mixed-species groups with the closely related Phayre’s langur (Trachypithecus phayrei). Recent studies in northeast Bangladesh confirm genetically that hybridisation is occurring, which could result in the eventual cyto-nuclear extinction of the capped langur lineage. Although hybridisation can happen naturally, in this case it is being driven by human-induced fragmentation, forcing species into overlapping territories with fewer options for mates. This phenomenon is both a symptom and a driver of their decline, complicating conservation efforts.

Mining, infrastructure, and political conflict

Open-cast coal mining, limestone extraction, and petroleum exploration have all contributed to the destruction of capped langur habitat across Assam and Nagaland. Infrastructure projects, such as highways and border fences, not only destroy habitat directly but also block animal movements and isolate populations. In border regions, armed conflict and territorial skirmishes have already extirpated capped langurs from several reserves, such as the Nambhur and Rengma forests. Weak law enforcement allows habitat destruction to continue unchecked in many regions.

Geographic Range

Capped langurs are found in northeastern India (Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram, and Tripura), Bhutan, northwestern Myanmar, and northeastern and central Bangladesh. They occur at elevations from 10 to 3,000 metres across hill forests, riverine reserves, and protected areas. However, their range is now severely fragmented by human development, with some populations disappearing from former strongholds due to mining, conflict, and agricultural encroachment.

Diet

Primarily folivorous, the capped langur’s diet includes mature and young leaves, petioles, seeds, flowers, bamboo shoots, bark, and occasionally caterpillars. They forage on more than 43 plant species, with favourites including banyan (Ficus benghalensis), sacred fig (Ficus religiosa), Terminalia bellerica, and Mallotus philippensis. Seasonal availability influences their feeding patterns, but they consistently prefer fruiting and flowering trees.

Mating and Reproduction

Breeding usually occurs in the dry season, with birthing concentrated between late December and May. The gestation period lasts about 200 days, and the interbirth interval is approximately two years. Only parous females participate in allomothering, allowing new mothers time to forage and recover, a behaviour rare among langurs and considered a form of altruism.

FAQs

How many capped langurs are left in the wild?

Exact numbers are uncertain, but estimates suggest the population in Assam has declined from 39,000 in 1989 to approximately 18,600 between 2008 and 2014 (Choudhury, 2014). This halving reflects habitat loss and increasing fragmentation, particularly in Upper Assam and the Barak Valley.

What is the average lifespan of a capped langur?

While data is limited, langurs of this genus generally live 20–25 years in the wild. Captive lifespans may extend slightly due to the absence of predators and constant food supply, though such conditions often lead to stress.

Why are capped langurs under threat?

Their decline is due to relentless deforestation, palm oil and monoculture plantations, illegal logging, and road-building. Slash-and-burn agriculture and mining also play a major role. Capped langurs are hunted in some regions for meat, pelts, and as pets, particularly in Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, and Nagaland.

Do capped langurs make good pets?

Absolutely not. Capped langurs are intelligent, social beings that rely on complex forest habitats and close-knit family groups. Removing them from the wild fuels extinction and causes immense trauma. Many die during illegal capture and transport. Keeping them as pets is a selfish act that destroys lives. If you care about capped langurs, never support the exotic pet trade!

What are the major conservation challenges for capped langurs?

The biggest issues are hybridisation with other primate species, habitat fragmentation, palm oil expansion, and human-wildlife conflict. The 2018 study in Satchari National Park found that local attitudes toward conservation vary by occupation, education, and gender, which means education and outreach are crucial. A big challenge is the rise in hybridisation with sympatric Phayre’s langurs, driven by habitat degradation—this poses long-term genetic risks (Ahmed et al., 2024).

Take Action!

Capped langurs are vanishing before our eyes, driven to the brink by out-of-control palm oil expansion, deforestation, and development. You can help save them.

Refuse to buy products made with palm oil. Support indigenous-led conservation in northeast India and the Eastern Himalayas. Demand governments halt the destruction of old-growth forests and restore wildlife corridors. Spread awareness and challenge the illegal wildlife trade. #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife #Vegan #BoycottMeat

Support the Capped Langur by going vegan and boycotting palm oil in the supermarket, it’s the #Boycott4Wildlife

Support the conservation of this species

This animal has no protections in place. Read about other forgotten species here. Create art to support this forgotten animal or raise awareness about them by sharing this post and using the #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife hashtags on social media. Also you can boycott palm oil in the supermarket.

Further Information

Ahmed, T., Hasan, S., Nath, S., Biswas, S., et al. (2024). Mixed-Species Groups and Genetically Confirmed Hybridization Between Sympatric Phayre’s Langur (Trachypithecus phayrei) and Capped Langur (T. pileatus) in Northeast Bangladesh. International Journal of Primatology, 46(1), 210–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-024-00459-x

Das, J., Chetry, D., Choudhury, A.U., & Bleisch, W. (2020). Trachypithecus pileatus (errata version published in 2021). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T22041A196580469. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22041A196580469.en

Hasan, M.A.U., & Neha, S.A. (2018). Group size, composition and conservation challenges of capped langur (Trachypithecus pileatus) in Satchari National Park, Bangladesh. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339550399

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Capped langur. Retrieved April 6, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capped_langur

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Learn about other animals endangered by palm oil and other agriculture

Learn about “sustainable” palm oil greenwashing

Read more about RSPO greenwashing

A 2019 World Health Organisation (WHO) report into the palm oil industry and RSPO finds extensive greenwashing of palm oil deforestation and the murder of endangered animals (i.e. biodiversity loss)

Discover more from Palm Oil Detectives

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.