Vordermann’s Flying Squirrel Petinomys vordermanni

Red List Status: Vulnerable

Locations: Malaysia (Peninsular Malaysia), Indonesia (Borneo, Belitung Island, Riau Islands), Myanmar (southern regions), Brunei

In #Borneo’s twilight, the Vordermann’s flying #squirrel emerges from her nest, resplendent with orange cheeks and black-ringed eyes. This small, #nocturnal #mammal is a master of the rainforest canopy. They use an ingenious membrane called a patagium to effortlessly glide between trees. A flying squirrel’s world is one of constant motion and quiet vigilance. Don’t let this world disappear! The forests that sustain them are vanishing at an alarming rate. Palm oil-driven deforestation, logging, and land conversion are tearing through their habitat, leaving only fragmented forest. Use your wallet as a weapon and #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife.

Vordermann’s Flying #Squirrels 🪽🦦🤎 are spectacular gliding #mammals of #Borneo who are #vulnerable due to #palmoil #deforestation in #Malaysia 🇲🇾 and #Indonesia 🇮🇩 Support them and #BoycottPalmOil 🌴🩸🚜🔥☠️❌ #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2021/02/05/vordermanns-flying-squirrel-petinomys-vordermanni/

Appearance and Behaviour

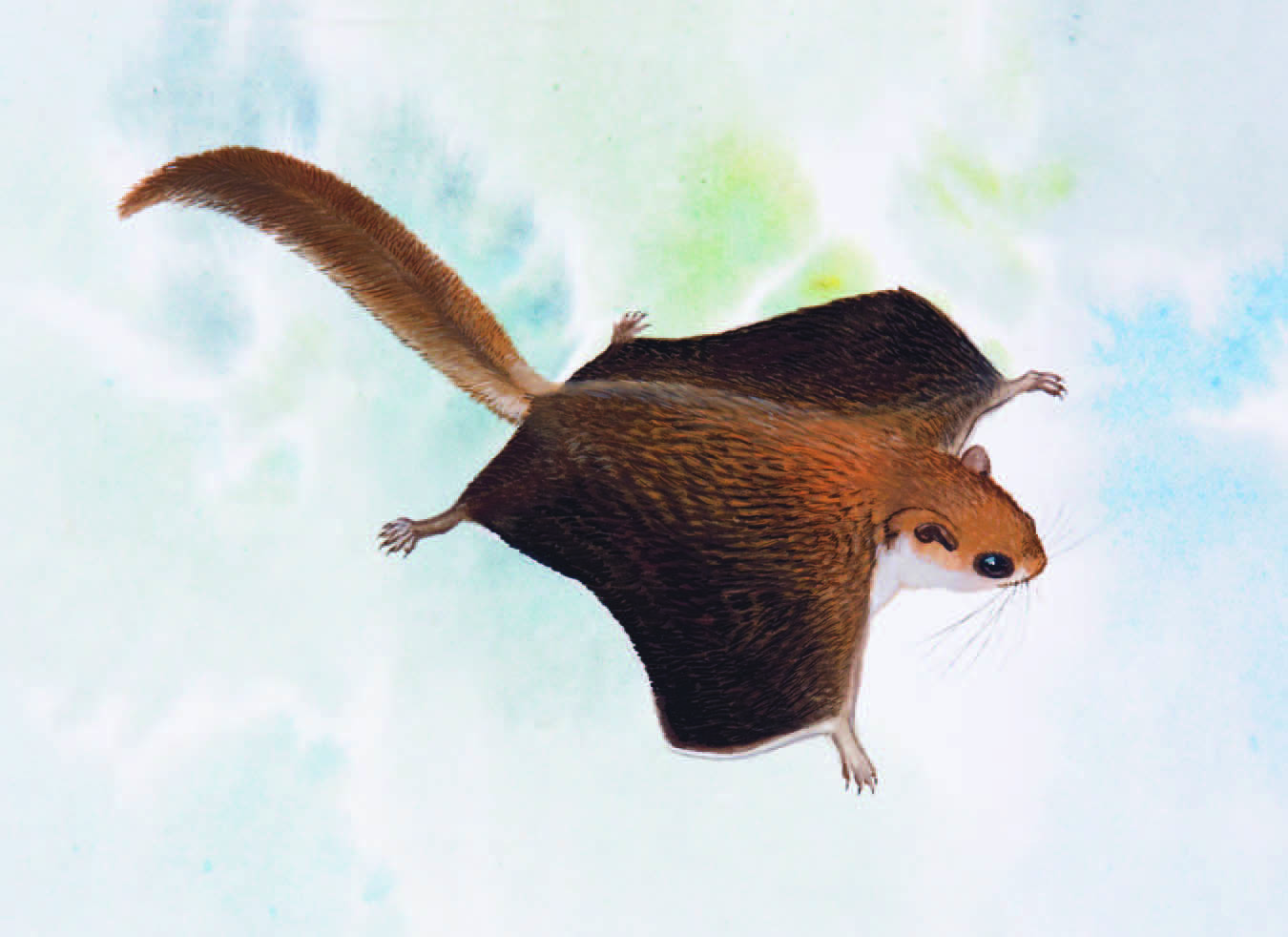

Vordermann’s flying squirrel is one of the smallest flying squirrels, with a head and body length of 92–120 millimetres and a tail of equal length, weighing between 22 and 52 grams. Their fur is a striking mix of black with rusty tips, and their underparts are a soft, rusty white. Each eye is ringed with black, and their orange cheeks and tufts of whiskers beneath the ears give them a distinctive, expressive face. The squirrel’s patagium—a skin flap between the limbs is like an airborne sail. Meanwhile their flattened bushy tail is akin to an airborne rudder helping them with precise movements through the air.

Vordermann’s flying squirrel is strictly nocturnal and arboreal, spending their days hidden in tree holes and emerging at night to forage and glide. They are agile climbers, using their sharp claws and keen senses to navigate the dense canopy. Their glides are silent and graceful, covering distances of several metres between trees. The squirrel’s world is one of constant movement and quiet communication, with little known about their social structure or vocalisations. Their nests are typically found 0.3 to 6 metres above the ground, often in partially cut primary forest, secondary forest, or forest bordering swamps.

Threats

This squirrel is threatened by forest loss due to logging and agricultural conversion.

IUCN Red list

Palm oil and other industrial agriculture

Vordermann’s flying squirrel is classified as Vulnerable on the Red List, with habitat loss the primary threat to their survival. Across Malaysia, Borneo, and Sumatra, forests are being cleared for palm oil plantations and agricultural expansion. These industrial-scale operations strip away the dense, multi-layered vegetation that the squirrel depends on for food and shelter. The once-continuous canopy is reduced to isolated patches, forcing squirrels into ever-smaller territories and increasing competition for resources.

Roads, infrastructure and timber logging

Logging operations further fragment the remaining forest habitat of Vordermann’s flying squirrel. Roads and clearings cut through the forest, severing the connections that squirrels rely on for movement and foraging. Fragmentation isolates populations, reducing genetic diversity and increasing vulnerability to disease and environmental change. In many areas, only small, isolated groups of squirrels remain, cut off from neighbouring populations by expanses of cleared land.

Hunting and illegal pet trade

While hunting and the illegal pet trade are not explicitly cited as major threats for Vordermann’s flying squirrel in current literature, the broader context of wildlife exploitation in Southeast Asia raises concerns. Any increase in human activity and access to remote forests could put additional pressure on this already vulnerable species.

Climate change and pollution

Climate change adds further pressure, altering rainfall patterns and the availability of food. The squirrel’s world is becoming hotter, drier, and less predictable, with the forests they depend on shrinking year by year. Extreme weather events, such as floods and droughts, can destroy habitat and isolate populations even further. Pollution from mining and agriculture can poison rivers and soil, further degrading the squirrel’s environment.

Diet

Vordermann’s flying squirrel is omnivorous, feeding on a variety of plant materials, including fruits, seeds, leaves, and bark, as well as insects and other small invertebrates. Their foraging is a quiet, nocturnal activity, carried out in the safety of the canopy. The rhythm of their feeding is woven into the life of the forest, as they play a vital role in seed dispersal and the regeneration of their ecosystem. The availability of food is closely tied to the health of the forest, and the loss of habitat threatens their ability to find enough to eat.

Reproduction and Mating

Vordermann’s flying squirrel is monogamous, with each female mating with a single male. Breeding occurs seasonally, typically in the spring months of February and March, and can extend into April. Females give birth to one to three young per litter, usually in tree holes. The gestation period and time to weaning are not well documented, but in similar species, mothers provide food and milk for several weeks until the young are able to forage on their own. Cooperative breeding may occur, with other group members assisting in the care of the young, but the exact social structure of Vordermann’s flying squirrel remains poorly understood.

Geographic Range

Vordermann’s flying squirrel is found in the lowland rainforests of southern Myanmar, Peninsular Malaysia, Borneo, and the Indonesian islands of Belitung and Riau. Their habitat includes primary and secondary forests, orchards, rubber plantations, and forests bordering swamps. The squirrel’s historical range has contracted due to deforestation and human encroachment, and they are now restricted to the few remaining patches of suitable habitat. The sounds of Vordermann’s flying squirrel—rustling leaves and silent glides—are now heard in fewer and fewer places.

FAQs

How many Vordermann’s flying squirrels are left?

There are no precise population estimates for Vordermann’s flying squirrel, but their numbers are believed to be declining due to ongoing habitat loss and fragmentation. The species is listed as Vulnerable on the Red List, with a suspected population decline of more than 30% over three generations. The squirrel’s survival is threatened by the continued destruction of their forest home.

What are the characteristics of Vordermann’s flying squirrel?

Vordermann’s flying squirrel is one of the smallest flying squirrels, with a head and body length of 92–120 millimetres and a weight of 22–52 grams. They have striking black fur with rusty tips, a white underside, and distinctive orange cheeks with black rings around their eyes. Their flattened, bushy tail and patagium allow them to glide silently through the forest canopy. Vordermann’s flying squirrel is strictly nocturnal and arboreal, spending their days in tree holes and emerging at night to forage.

Where does the Vordermann’s flying squirrel live?

Vordermann’s flying squirrel is found in the lowland rainforests of southern Myanmar, Peninsular Malaysia, Borneo, and the Indonesian islands of Belitung and Riau. They inhabit primary and secondary forests, orchards, rubber plantations, and forests bordering swamps. Their historical range has contracted due to deforestation and human encroachment, and they are now restricted to the few remaining patches of suitable habitat.

What are the threats to the survival of the Vordermann’s flying squirrel?

The main threats to the survival of Vordermann’s flying squirrel are habitat loss and fragmentation caused by palm oil-driven deforestation, logging, and agricultural expansion. The forests of Malaysia, Borneo, and Sumatra are being cleared at an alarming rate, leaving only isolated patches where the squirrel can survive. Fragmentation isolates populations, reducing genetic diversity and increasing vulnerability to disease and environmental change. Climate change and pollution add further pressure, altering the availability of food and shelter.

Do Vordermann’s flying squirrels make a good pets?

Vordermann’s flying squirrels most definitely do not make good pets. Captivity causes extreme stress, loneliness, and early death for these highly specialised forest animals. The illegal pet trade rips families apart and fuels extinction, as animals are stolen from their natural habitat and forced into unnatural, impoverished conditions. Protecting Vordermann’s flying squirrel means rejecting the illegal pet trade and supporting their right to live wild and free in their forest home.

Take Action!

Use your wallet as a weapon and #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife. Support indigenous-led conservation and agroecology. Reject products linked to deforestation, mining, and the illegal wildlife trade. Adopt a #vegan lifestyle and #BoycottMeat to protect wild and farmed animals alike. Every choice matters—stand with Vordermann’s flying squirrel and defend the forests of Southeast Asia.

Support the conservation of this species

This animal has no protections in place. Read about other forgotten species here. Create art to support this forgotten animal or raise awareness about them by sharing this post and using the #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife hashtags on social media. Also you can boycott palm oil in the supermarket.

Further Information

Clayton, E. 2016. Petinomys vordermanni (errata version published in 2017). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T16740A115139026. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T16740A22241246.en. Downloaded on 04 February 2021.

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Vordermann’s flying squirrel. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vordermann%27s_flying_squirrel

Wilson, D. E., Lacher, T. E., & Mittermeier, R. A. (2016). Sciuridae, Handbook of the Mammals of the World – Volume 6 Lagomorphs and Rodents I. Lynx Edicions. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6840226

Caption: This beautiful painting is by My YM

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Discover more from Palm Oil Detectives

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.