Hippopotamus Hippopotamus amphibius

IUCN Red List Status: Vulnerable

Locations: Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Kenya, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, Swaziland, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Republic of Congo, South Africa, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

Extinct: Algeria; Egypt; Eritrea; Liberia; Mauritania

The Common Hippopotamus, or Hippo, is a powerful and enduring symbol of Africa’s rivers and wetlands. Once common throughout all of Africa and the revered subjects of African folklore —their populations are now in peril. Hippo numbers plummeted in the 1990s and early 2000s due to unregulated #hunting and land conversion for #palmoil #cocoa and #tobacco #agriculture and human settlement. Although some strongholds remain in East and Southern Africa, many populations are in decline across #WestAfrica and Central Africa. Hippos are now listed as #Vulnerable on the Red List, with threats from freshwater habitat loss, illegal hunting for meat and ivory, and increasing conflicts with people. Use your voice and your wallet to push for stronger protections for Hippos and their riverine homes. #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife

#Hippos secrete red sweat to stay cool in #WestAfrica 🦛 Although #herbivores, parents fiercely protect infants leading to conflict with people. #PalmOil and #tobacco #deforestation are threats. #BoycottPalmOil 🌴⛔️ #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2022/06/29/hippopotamus-hippopotamus-amphibius/

#Hippos 🦛🩶 were once found all over Africa. They’re revered subjects of ancient #folklore. Now they’re vulnerable due to #palmoil expansion, conflict with humans and #poaching. Help them and #BoycottPalmOil 🌴🪔💀🤮🚫 #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2022/06/29/hippopotamus-hippopotamus-amphibius/

Appearance and Behaviour

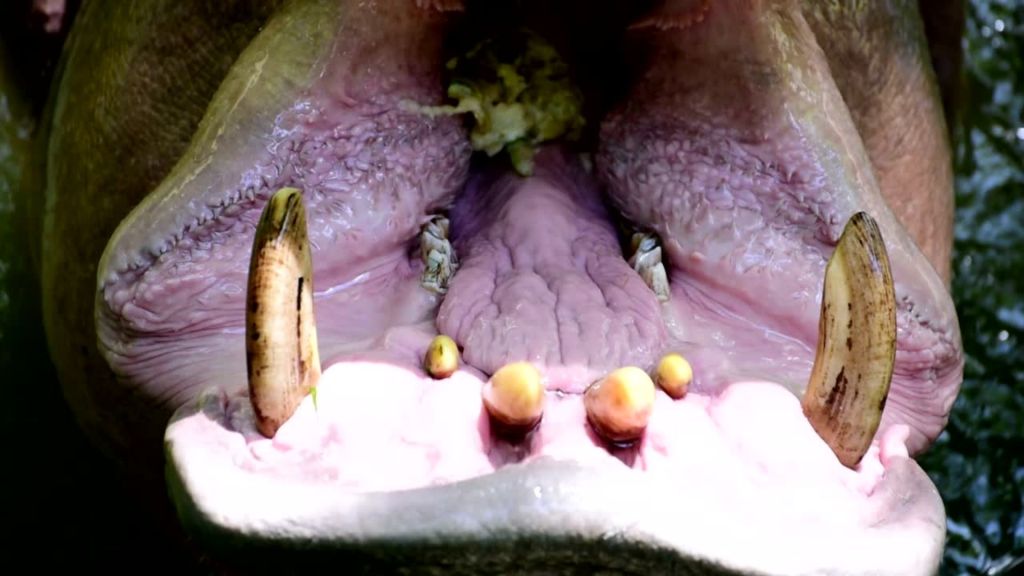

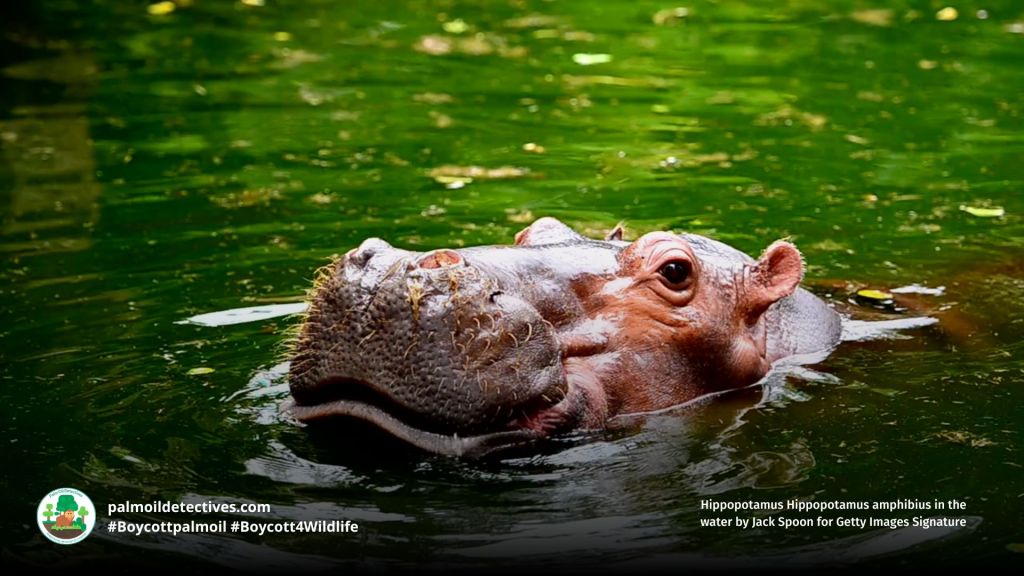

Bulky yet graceful in the water, Common Hippos are unmistakable. With barrel-like bodies, glistening greyish-brown skin, and short legs ending in splayed, webbed toes, they cut a surreal figure at sunset when emerging to graze. Their broad heads house fearsome canines, but their expression is often curiously serene. Most evocatively, Hippos secrete a crimson, oily substance sometimes called ‘blood sweat’—a natural sunscreen and antibiotic that turns red on exposure to air (Saikawa et al., 2004). This vivid secretion lends them a mythical quality.

Hippos spend the day submerged in rivers or lakes, clustered together in herds called schools. At night, they trudge kilometres from water to feed. Though sociable in water, they become solitary on land. Territorial males guard stretches of water, with fierce battles and dramatic yawns serving as display and deterrent. Vocalisations resonate both above and below water—a rare feat among mammals.

Diet

The primary threats to Common Hippos are habitat loss or degradation and illegal and unregulated hunting for meat and ivory (found in the canine teeth). Habitat loss and conflict with agricultural development and farming are a major problem for hippo conservation in many countries (Brugière et al. 2006, Kanga 2013, Kendall 2013, Brugière and Scholte 2013).

IUCN red list

Despite their massive size, Hippos are grazers. Emerging at night, they nibble short grasses using their muscular lips. Their diet consists mainly of terrestrial grass species, not aquatic plants. Hippo lawns—regularly grazed pastures—are shaped by their nightly foraging. Their specialised gut supports fermentation similar to ruminants, but they do not chew cud.

Reproduction and Mating

Common Hippos follow a polygynous breeding system with dominant males controlling access to a group of females within a territory. Mating occurs in water, often accompanied by loud vocalisations and displays. Females become sexually mature between the ages of seven and nine, while males reach maturity around nine to eleven years of age. Breeding can occur year-round, but peaks during the rainy season when water levels rise, facilitating easier movement and access to mating territories. After a gestation period of around eight months, a female usually gives birth to a single calf, often in the water.

Newborn calves weigh between 25–50 kilograms and can suckle underwater thanks to special adaptations that close their ears and nostrils. They remain close to their mother for protection, often riding on her back in deep water. Lactation can continue for 12–18 months, and females generally breed only once every two years due to the extended maternal care required. Mothers are fiercely protective and may attack humans who unknowingly approach too closely to a calf, especially near riverbanks. This maternal aggression is one of the reasons Hippos are considered one of Africa’s most dangerous animals to humans.

Geographic Range

Common Hippos once ranged widely across sub-Saharan Africa and remain present in 38 countries, though often in fragmented populations. Eastern and Southern Africa harbour the largest populations—particularly in Tanzania, Zambia, and Uganda. West African populations are increasingly isolated and endangered, including small numbers in Côte d’Ivoire, Benin, Guinea, and Guinea-Bissau. Civil unrest, poaching, and habitat loss have devastated populations in countries like DRC and Mozambique. Some of the last hippos in West Africa reside in tiny enclaves of Niger, Burkina Faso, and Cameroon.

Threats

Common Hippos were already rare in Egypt by the time of the Renaissance. Although they were the subject of reverence for many ancient peoples of Africa including the Ancient Egyptians. From the end of the Roman Empire up until circa 1700, hippos still lived in the Nile Delta and in the upper Nile. Throughout the 1700s, records become increasingly scarce, and the latest definite records are from the early 1800s. Hippopotamuses face serious human-related threats to their ongoing survival.

Habitat Loss and Degradation

The rapid expansion of agriculture, damming of rivers, and industrial development has drastically altered freshwater systems across Africa. Hippos rely on permanent water bodies for thermoregulation and reproduction. When rivers are drained or diverted, or wetlands are converted into farmland, Hippos are cut off from grazing lands and breeding sites. In areas such as Ethiopia and Burkina Faso, increasing demand for water has fragmented habitats, forcing Hippos into smaller and more vulnerable populations (Jacobsen & Kleynhans, 1993; Brugière & Scholte, 2013). Without reliable access to water, Hippos suffer from cracked skin, heat stress, and reduced reproductive success.

Human-Wildlife Conflict

Hippos are responsible for more human deaths in Africa than most other large mammals. These incidents often occur when people fish or wash in rivers used by Hippos, who perceive human presence as a threat. Male Hippos are highly territorial and will violently defend their stretch of river, while females will charge to protect their calves. As Hippo habitats shrink, they are forced closer to human settlements, increasing encounters. Crop-raiding is also a growing issue, with Hippos destroying maize and rice fields during night-time grazing, leading to retaliation by farmers (Kanga, 2013; Mackie et al., 2013).

Illegal and Unregulated Hunting

Hippos are hunted for their meat, hides, and particularly for their canine teeth, which are used as ivory. Following the 1989 elephant ivory ban, the demand for Hippo ivory skyrocketed. TRAFFIC reported an increase in illegal Hippo ivory exports in the early 1990s, with thousands of kilograms seized en route to Asia (Weiler et al., 1994; TRAFFIC, 1997). During periods of civil unrest, such as in DR Congo and Mozambique, Hippo populations plummeted due to unregulated military hunting and widespread poaching. In some areas of DR Congo, over 95% of the Hippo population was lost within a few years (Hillman Smith et al., 2003).

Climate Change and Water Scarcity

Changes in rainfall patterns and increasing drought frequency due to climate change are reshaping African river ecosystems. Hippos, as semi-aquatic mammals, are particularly sensitive to drying water bodies. During the dry season, Hippo dung accumulates in shrinking pools, causing eutrophication and oxygen depletion. This not only threatens aquatic biodiversity but also affects Hippo health by concentrating pathogens and reducing water quality (Stears et al., 2018). Furthermore, rising temperatures and unreliable water flows increase the risk of human-Hippo encounters at scarce water sources, further escalating conflict.

Civil Unrest and Armed Conflict

In countries plagued by war or political instability, Common Hippos have suffered catastrophic losses due to unregulated military hunting and opportunistic poaching. During civil wars in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Mozambique, armed groups and soldiers slaughtered thousands of Hippos for meat and ivory. In Virunga National Park alone, Hippo populations declined by over 95% in less than a decade as rebel forces and militia targeted them with impunity (Hillman Smith et al., 2003). These environments of lawlessness eliminate enforcement of conservation laws, opening floodgates for the commercial bushmeat and ivory trade. In South Sudan and parts of Central Africa, similar losses continue today where violence prevents any formal protection or population monitoring.

Take Action!

Protecting Common Hippos requires urgent, coordinated action across the continent. Boycott palm oil and all industries contributing to wetland destruction. Amplify support for indigenous-led conservation of river systems and call for crackdowns on the illegal hippo ivory trade. Demand freshwater access for wildlife, not just profit-driven palm oil agriculture. #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife, be #Vegan for them and #BoycottMeat

FAQs

How many Common Hippos are left in the wild?

The current global estimate is between 115,000 and 130,000 individuals (IUCN, 2017). This is a decline from earlier estimates of up to 148,000, with significant regional variation—populations are stable or increasing in Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia but shrinking or disappearing in West and Central Africa.

How long do Hippos live?

In the wild, Hippos live around 40–50 years, and up to 60 years in captivity (Lewison, 2007). Their lifespan depends heavily on access to water, food, and protection from hunting or conflict.

Why are Hippos important to the environment?

Hippos are ecosystem engineers. Their nightly grazing maintains short grasslands, and their faeces fertilise aquatic systems, fuelling food chains and altering river ecology (Subalusky et al., 2014; Voysey et al., 2023). They shape riverbanks, widen channels, and transport nutrients between land and water.

Do Hippos make good pets?

Hippos are wild animals and they are not ideal for captive display in zoos or for private ownership. Keeping a hippo is both unethical and ecologically disastrous. They are wild megafauna that require vast territories, water access, and complex social structures. Their removal from the wild contributes to extinction and suffering. No one who loves animals should ever support the exotic pet trade or the Zoo trade.

You can support this beautiful animal

Donate to Virunga National Park which supports and protects a wild population of hippos.

Further Information

Lewison, R. & Pluháček, J. 2017. Hippopotamus amphibius. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T10103A18567364. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T10103A18567364.en.

Saikawa, Y., Hashimoto, K., Nakata, M., Yoshihara, M., Nagai, K., Ida, M., & Komiya, T. (2004). Pigment chemistry: The red sweat of the hippopotamus. Nature, 429(6990), 363. https://doi.org/10.1038/429363a

Stears, K., McCauley, D. J., Finlay, J. C., et al. (2018). Effects of the hippopotamus on the chemistry and ecology of a changing watershed. PNAS, 115(22), E5028–E5037. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1800407115

Subalusky, A. L., Dutton, C. L., Rosi-Marshall, E. J., & Post, D. M. (2014). The hippopotamus conveyor belt: vectors of carbon and nutrients. Freshwater Biology, 59(5), 965–978. https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.12474

Voysey, M. D., de Bruyn, P. J. N., & Davies, A. B. (2023). Are hippos Africa’s most influential megaherbivore? Biological Reviews, 98(3), 1242–1262. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12960

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Discover more from Palm Oil Detectives

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.