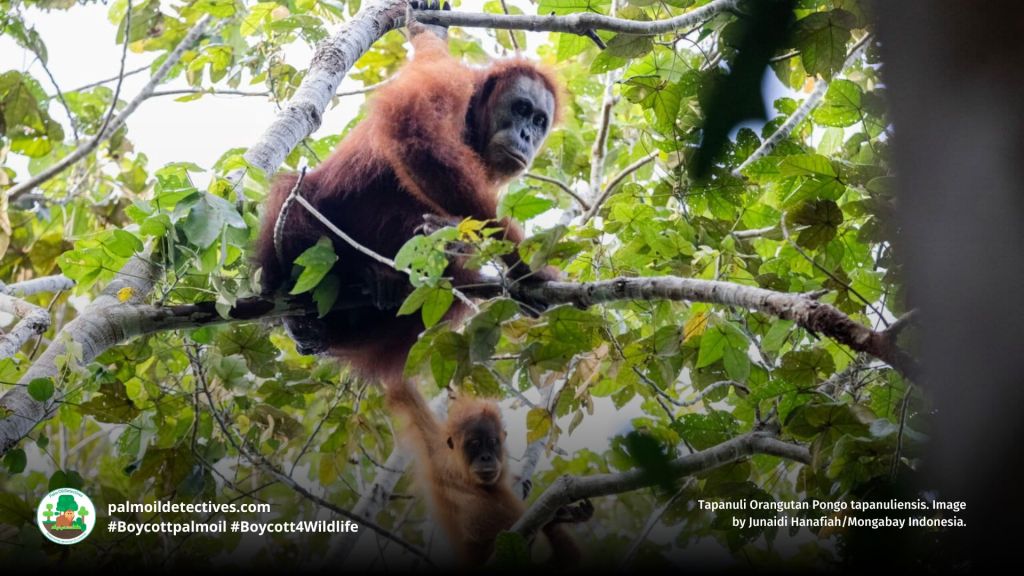

Tapanuli Orangutan Pongo tapanuliensis

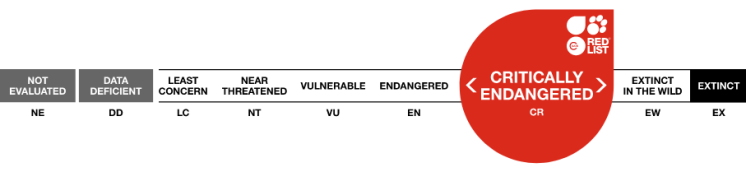

IUCN Red List: Critically Endangered

Locations: Found only in the Batang Toru Ecosystem in North Sumatra, Indonesia.

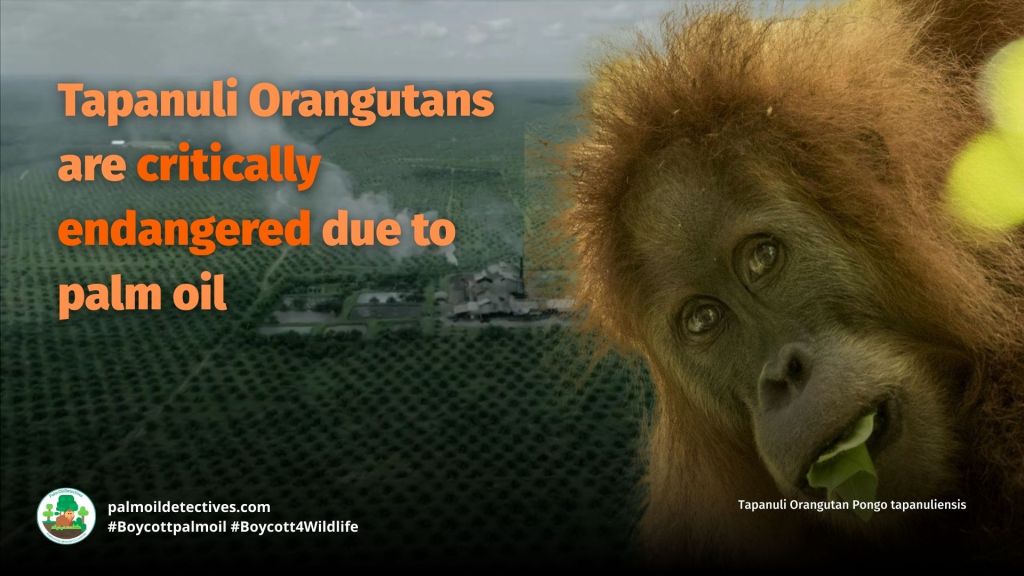

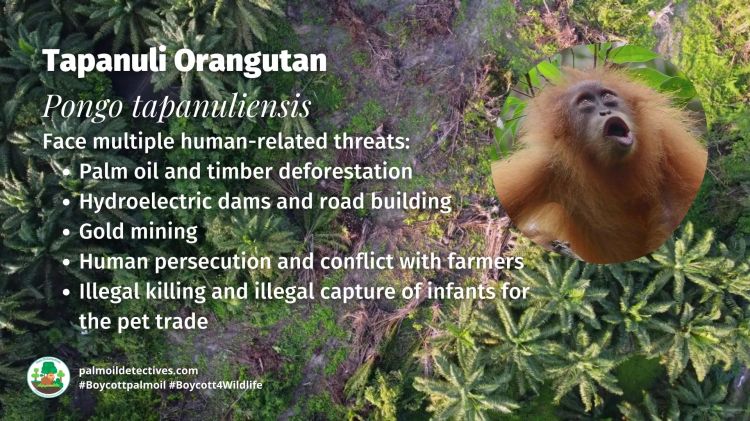

The Tapanuli #Orangutan Pongo tapanuliensis is the most endangered #greatape species on Earth, with fewer than 800 individuals surviving in the wild. Listed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN, they are confined to a tiny mountainous area of primary rainforest in the Batang Toru Ecosystem #Indonesia. Their survival is threatened by relentless industrial expansion—#hydroelectric dams, gold mines, geothermal projects—and vast deforestation for palm oil and rubber plantations. As a keystone species, their survival is vital to the entire ecosystem. We must act urgently to protect them. #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife

Just 800 Tapanuli Orangutans remain alive due to #palmoil and #mining #deforestation. If you find their imminent #extinction a disgrace 😡‼️ – there’s something you can do! #BoycottPalmOil 🌴☠️🚫 #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2021/01/19/tapanuli-orangutan-pongo-tapanuliensis/

The rarest species of #orangutan, the #Tapanuli is on the verge of being lost due to #palmoil and #mining #deforestation destroying 80% of their range. Say no to #ecocide ⛔️🙊🔥🌴🪔 when u shop #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect.bsky.social https://palmoildetectives.com/2021/01/19/tapanuli-orangutan-pongo-tapanuliensis/

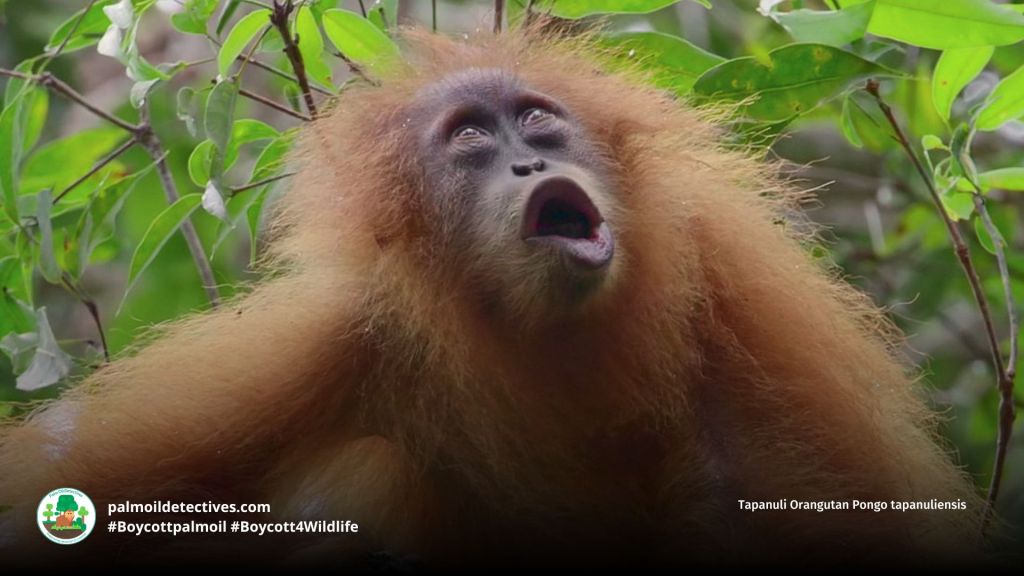

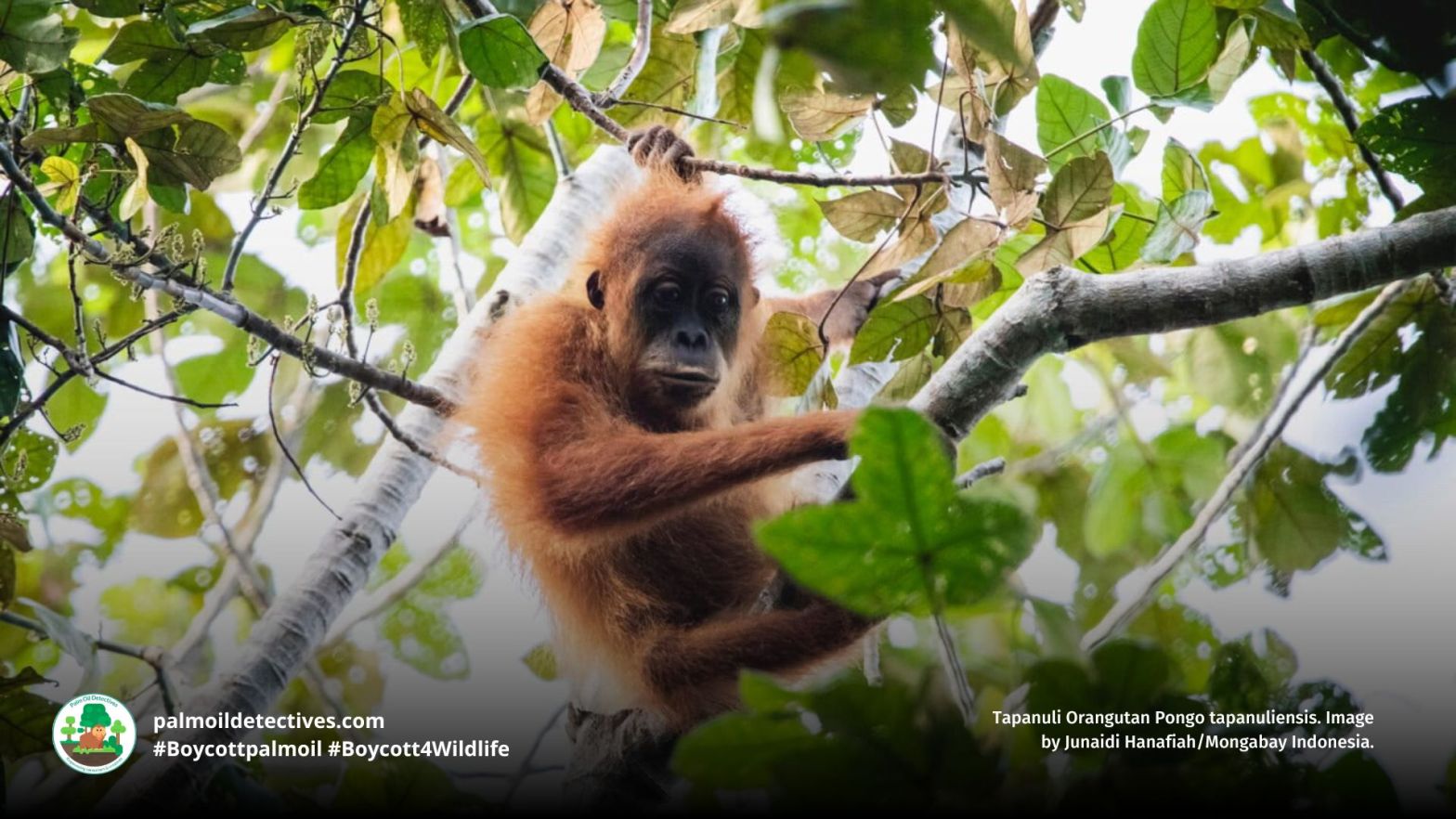

Appearance and Behaviour

With expressive faces and a deep orange coat, the Tapanuli Orangutan shares similarities with their Sumatran Orangutan and Bornean Orangutan cousins, but they are genetically and physically distinct. They possess frizzier hair, smaller skulls, flatter faces, and a more prominent moustache. Adult males have uniquely shaped flanges and emit a long call that is subtly different from other orangutans, showing acoustic divergence linked to genetic isolation.

Tapanuli Orangutans live solitary lives or in small, loose social groups. They are primarily arboreal, building elaborate sleeping nests in the forest canopy each night. Recent drone studies by Rahman et al. (2025) confirmed their high canopy preference, and the use of thermal sensors detected individuals invisible to the human eye. These shy forest dwellers avoid human presence and vanish into the dense trees with startling ease.

Diet

Dietary studies from the Tapanuli Orangutan Research Station (Arief & Mijiarto, 2024) recorded 91 plant species consumed, including fruits, young leaves, flowers, bark, and insects. While fruit forms the core of their diet, they also consume termites and other invertebrates when fruit is scarce. Figs, durians, and forest fruits are critical seasonal food sources, and loss of these plants due to palm oil plantations may lead to starvation.

Reproduction and Mating

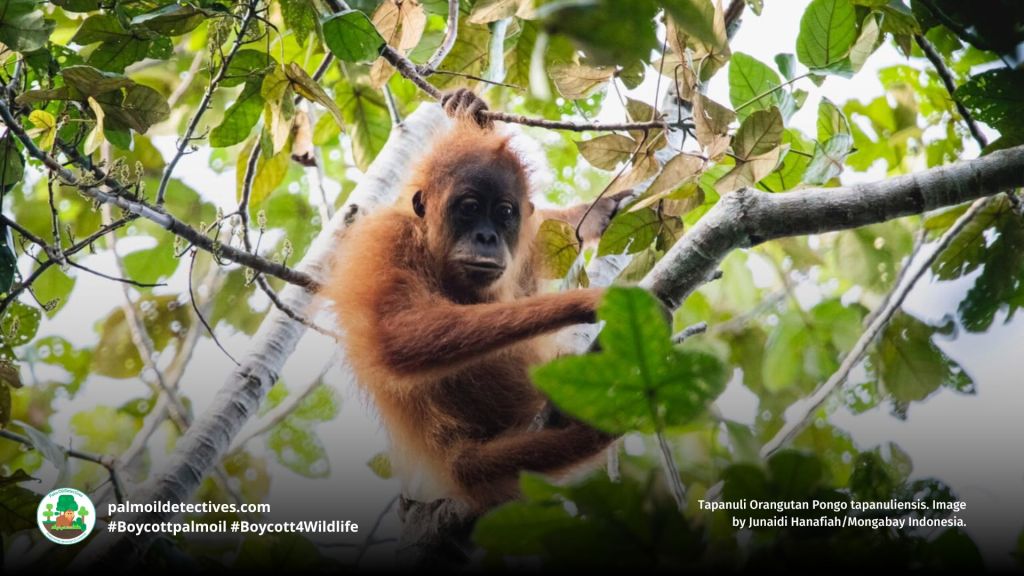

Tapanuli Orangutans have an extremely slow reproductive rate. Females give birth once every 6–8 years after a gestation of 8.5 months. Infant orangutans remain with their mothers for up to 9 years, learning complex forest survival skills. This slow life history makes them exceptionally vulnerable—losing even a few individuals per year could doom the entire species. Population viability studies predict an 83% decline over three generations without immediate intervention (Wich et al., 2016).

Geographic Range

Once found across a vast swathe of southern Sumatra, the Tapanuli Orangutan now survives in only three isolated forest blocks of the Batang Toru Ecosystem—just 1,500 km². Only 10% of this is formally protected. Historical records suggest they once roamed as far south as Jambi and Palembang, but massive deforestation and human persecution have erased them from most of their former range. Their current habitat is dissected by roads, mines, and farmland.

Threats

The Tapanuli Orangutan was until relatively recently more widespread, with sightings further south in the lowland peat swamp forests in the Lumut area (Wich et al. 2003) and several nests encountered during a rapid survey in 2010 (G. Fredriksson pers. obs.). The forests in the Lumut area have in recent years almost completely been converted to oil-palm plantations.

IUCN Red List

Agro-industrial Expansion for Palm Oil and Rubber

The most significant threat to the Tapanuli Orangutan (Pongo tapanuliensis) is the relentless conversion of their highland forest habitat into industrial monocultures—particularly palm oil plantations, but also rubber and coffee. A 2024 study highlighted how forest clearance for oil palm, coffee, and rubber cultivation in the Batang Toru Ecosystem has devastated vital orangutan habitat, triggering migration into village gardens and escalating human-orangutan conflict (Lesmana et al., 2024). Wich et al. (2016) further underscore that nearly 14% of the orangutan’s range lacks any form of protection and is especially vulnerable to conversion. Entire lowland forest systems, such as those in the Lumut area, have been obliterated and replaced with palm oil plantations. The habitat loss is not only large-scale but also permanent, given the legal backing often enjoyed by agribusiness in Sumatra.

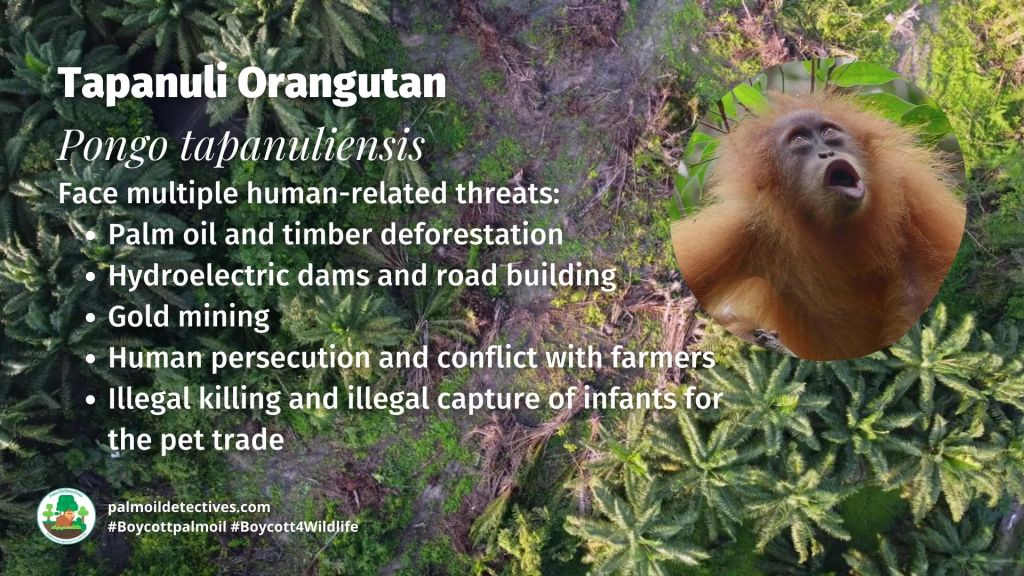

Infrastructure Development: Hydroelectric dams, roads and gold mining

A controversial Chinese-funded hydropower project threatens to destroy 10% of the Tapanuli Orangutan’s population. Located in the highest-density area of their range, the project will fragment habitat and block genetic flow for Tapanuli Orangutans and make the population vulnerable to collapse (Wich et al., 2019; Lesmana et al., 2024).

Gold and silver mining operations have already cleared approximately 3 km² of orangutan habitat and continue to expand. Compounding these threats, newly constructed roads have opened up previously inaccessible areas, accelerating both forest encroachment and illegal wildlife trade. As highlighted in the Floresta Ambient study (2024), such development has profoundly altered orangutan behaviour, pushing them into conflict with nearby communities.

Illegal Logging and Land Speculation

Despite the 2014 reclassification of parts of the Batang Toru forest from production to protection status, logging continues under outdated or contested permits. One company retains a 300 km² logging permit that cuts through primary orangutan habitat (Wich et al., 2016).

This deforestation is often driven by speculative land grabbing, with companies clearing forest to increase the value of land holdings. Encroachment is further driven by economic migrants, particularly from Nias Island, who settle in these unallocated forests due to lack of land tenure regulation. These migrants frequently convert forested land to agriculture, directly encroaching upon orangutan territories and escalating poaching and human-wildlife conflict (Samsuri et al., 2023).

Human-Orangutan Conflict, Illegal Hunting and the Illegal Pet Trade

Hunting poses a severe and often overlooked threat to the Tapanuli Orangutan. Conflict killings occur when orangutans forage in fruit trees or crops near villages, with some individuals shot with firearms or air rifles during crop conflict. With such a small population, every death is devastating. Orangutan infants are often trafficked for the exotic pet trade after their mothers are killed. According to Wich et al. (2012), the species’ slow reproductive rate makes any loss of adult females—particularly those with offspring—catastrophic for population viability.

The Floresta Ambient (2024) study documents that fruit-bearing trees in village gardens are a primary attractant for orangutans, intensifying seasonal conflict. Despite laws prohibiting the capture and trade of orangutans under CITES Appendix I, enforcement remains weak, and the trade persists.

Take Action!

We are at a tipping point. Only decisive action will save the Tapanuli Orangutan:

- Boycott palm oil every time you shop – learn more here.

- Oppose and resist destructive hydroelectric projects like the Batang Toru dam.

- Support local conservation groups and indigenous-led protection of the Batang Toru forest.

- Demand a moratorium on mining and infrastructure projects in orangutan habitat.

#BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife

FAQs

How many Tapanuli orangutans are left in the wild?

The Tapanuli orangutan (Pongo tapanuliensis) is the rarest great ape on Earth, with fewer than 800 individuals remaining in the wild. This species is confined to a single, highly fragmented population in the Batang Toru Ecosystem of North Sumatra. According to Wich et al. (2016), the total area of suitable habitat is just over 1,000 km², making their population extremely vulnerable to stochastic events, inbreeding, and continued habitat degradation. A 75-year population viability analysis predicted a staggering decline from ~1,489 individuals in 1985 to just 257 by 2060 without urgent intervention (Wich et al., 2019).

Surveys using innovative thermal drone technology in 2023 confirmed that detection rates are consistent between aerial and ground methods, affirming the grim reality of their numbers (Rahman et al., 2025). With extremely low reproduction rates (a female produces one offspring every 7–9 years), any mortality has a profound impact on population dynamics. The population’s isolation and the lack of genetic exchange further endanger its viability, pushing the species closer to extinction unless dramatic changes are made to protect and connect its remaining habitat (Nater et al., 2017).

How long do Tapanuli orangutans live?

In the wild, Tapanuli orangutans are believed to live approximately 30 to 40 years, with some individuals possibly reaching 50. In captivity, individuals can live up to 60 years when protected from threats and given regular medical care. However, data specific to Pongo tapanuliensis are limited, as they have only recently been recognised as a separate species (Nater et al., 2017). Like other great apes, their slow reproductive cycle means that females generally give birth once every 7–9 years, and juveniles remain dependent on their mothers for up to 8 years. This slow life history leaves them especially vulnerable to population crashes when faced with increased mortality from hunting, habitat loss, or conflict (Wich et al., 2019).

The longevity of these apes in the wild is severely compromised by anthropogenic threats. Conflict with humans over fruiting crops, road construction, and the development of hydropower dams has placed increasing stress on their ecosystem, reducing not only the lifespan of individuals due to direct killings but also the carrying capacity of their habitat. Without the intact rainforest necessary to support their dietary and nesting needs, lifespans are likely to decline further, particularly for juvenile apes displaced or orphaned by habitat destruction (Samsuri et al., 2023).

Why are Tapanuli orangutans disappearing?

Tapanuli orangutans are being driven to extinction by a lethal cocktail of deforestation, infrastructure development, mining, poaching, and habitat fragmentation. Between 1985 and 2007, lowland forest habitat below 500 m was reduced by 60% due to palm oil plantations, road construction, and smallholder agriculture (Wich et al., 2016). These losses have accelerated in recent years, with one of the most devastating developments being the Batang Toru hydroelectric dam, which threatens to sever key corridors connecting their small subpopulations and destroy 10% of their core habitat (Rahman et al., 2025).

In addition, illegal killings are rising due to human-orangutan conflict, especially where crops like durians and jackfruit attract hungry apes into village fields. Surveys in the Dolok Sipirok region found that most conflicts occurred on the edge of forest areas where agriculture has expanded, resulting in economic losses for local people and retaliation killings of orangutans (Floresta Ambient, 2024). These apes are also at risk from trafficking—juveniles are captured for the pet trade, and their mothers are often killed in the process. As these apes only give birth once every 7–9 years, even the loss of a few individuals each year can rapidly collapse the population.

Are Tapanuli orangutans affected by palm oil plantations?

Yes, palm oil expansion is one of the most significant threats to the Tapanuli orangutan’s survival. Forest clearance for palm oil plantations has already wiped out entire swathes of their historic range, especially in the lowland areas of Lumut. These forests were once part of their known distribution, but have now been almost entirely replaced by monocultures of oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) (Wich et al., 2016; Nater et al., 2017). Such plantations are ecologically barren for orangutans, offering no food, nesting sites, or safety, while exposing them to poaching and conflict with humans.

The construction of roads and industrial developments linked to palm oil has fragmented orangutan habitat, making it harder for individuals to move safely between feeding and nesting areas. This fragmentation reduces genetic diversity and increases the risk of inbreeding, which has already been detected in Tapanuli orangutan genomes (Nater et al., 2017). Beyond habitat loss, palm oil plantations bring human settlements, increased hunting, and indirect threats like noise pollution and chemical runoff. As seen across Sumatra and Borneo, the palm oil industry’s unchecked expansion continues to destroy the last refuges for Asia’s great apes, including the critically endangered Tapanuli orangutan.

Is poaching and illegal trade still a problem for Tapanuli orangutans?

Absolutely. Despite national and international protection, Tapanuli orangutans are still poached, particularly in areas where they forage on cultivated fruit trees, triggering conflict with farmers. According to Samsuri et al. (2023), human-wildlife conflict is one of the strongest predictors of orangutan mortality in the region. Infants are especially at risk from the pet trade; mothers are frequently killed to take babies alive. These infants are then smuggled and sold illegally, often under the guise of ecotourism or exotic pet ownership.

Lack of enforcement is a major factor behind the persistence of illegal trade. While Indonesia has laws against orangutan capture and trade, penalties are rarely enforced and often misunderstood by local communities (Lesmana et al., 2024). Furthermore, conservation areas are often poorly monitored. Forest edge communities facing economic hardship may view orangutans as pests or potential profit. Unless conservation is led by local people and grounded in economic alternatives to poaching and deforestation, the illegal killing of orangutans will continue unchecked.

Can drones help monitor their numbers?

Yes. A 2023 drone study (Rahman et al., 2025) showed thermal drones are effective in detecting orangutans through dense canopy, offering a non-invasive tool for population monitoring.

Further Information

Arief, H., & Mijiarto, J. (2024). Food diversity of the Tapanuli Orangutan (Pongo tapanuliensis) in the Tapanuli Orangutan Research Station Plan, North Sumatra. Jurnal Pengelolaan Sumberdaya Alam dan Lingkungan, 14(2), 376–388. https://doi.org/10.29244/jpsl.14.2.376

Arief, H., & Mijiarto, J. (2024). The human and Tapanuli orangutan (Pongo tapanuliensis) conflict in the tropical mountain rainforest ecosystem, Indonesia. Floresta e Ambiente, 31(1). https://doi.org/10.1590/2179-8087-FLORAM-2023-0019

Lesmana, Y., Basuni, S., & Soekmadi, R. (2024). Ecosophy as a form of protection for the Tapanuli Orangutan (Pongo tapanuliensis) in the Batang Toru Landscape, North Sumatra. Biodiversitas, 25(11), 4535–4542. https://doi.org/10.13057/biodiv/d251152

Nater, A., Mattle-Greminger, M. P., Nurcahyo, A., Nowak, M. G., De Manuel, M., Desai, T., & Lameira, A. R. (2017). Morphometric, behavioural, and genomic evidence for a new orangutan species. Current Biology, 27(22), 3487–3498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.047

Nowak, M.G., Rianti, P., Wich , S.A., Meijaard, E. & Fredriksson, G. 2017. Pongo tapanuliensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T120588639A120588662. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T120588639A120588662.en. Downloaded on 24 January 2021.

Rahman, D. A., Putro, H. R., Mufawwaz, T. A., Rinaldi, D., Yudiarti, Y., Prabowo, E. D., Arief, H., Sihite, J., & Priantara, F. R. N. (2025). Developing a new method using thermal drones for population surveys of the world’s rarest great ape species, Pongo tapanuliensis. Global Ecology and Conservation, 58, e03463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2025.e03463

Samsuri, A., Zaitunah, A., Ashari, R. H., & Kuswanda, W. (2023). Biophysical and anthropogenic factors affecting human and Tapanuli orangutan (Pongo tapanuliensis) conflict in Sumatran tropical rainforest, Indonesia. Environmental & Socio-economic Studies, 11(4), 77–91. http://bazekon.icm.edu.pl/bazekon/element/bwmeta1.element.ekon-element-000171681828

Wich, S. A., Fredriksson, G. M., Usher, G., & Kühl, H. S. (2019). The Tapanuli orangutan: Status, threats, and steps for improved conservation. Conservation Science and Practice, 1(4), e33. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.33

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Discover more from Palm Oil Detectives

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Tapanuli Orangutan Pongo tapanuliensis”