Thomas’s Langur Presbytis thomasi

IUCN Status: Vulnerable (VU)

Location: Indonesia – Sumatra (Aceh Province)

Thomas’s Langur, also known as the North Sumatran Leaf #Monkey is famous for their bold facial stripes giving them a handsome profile. These monkeys are endemic to the lush forests of northern Sumatra, Indonesia. Listed as Vulnerable by the Red List, this striking species is facing serious population declines due to habitat loss, primarily driven by illegal logging and oil palm deforestation. Though not as globally known as some of its neighbours, such as the Sumatran Orangutan, Thomas’s Langur plays an equally vital role in forest regeneration and seed dispersal. You can help protect them by using your consumer power: always choose palm oil-free products.#BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife #Vegan

The Thomas’s #Langur has striking stripes 🐵🐒🤎 They’re #vulnerable due to forest clearance for #palmoil and #timber in #Sumatra #Indonesia 🇮🇩 Protect this rare #monkey when you shop and #BoycottPalmOil 🌴🪔☠️🩸🤮🙊🚫 #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2021/01/24/thomass-langur-presbytis-thomasi/

Sporting bold facial stripes, the Thomas’s #Langur is a handsome icon of #Sumatra #Indonesia 🇮🇩 Threats include #palmoil #deforestation and human persecution 🏹😿 Fight for their survival and #BoycottPalmOil 🌴🪔☠️🩸🤮🙊🚫 #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2021/01/24/thomass-langur-presbytis-thomasi/

Appearance and Behaviour

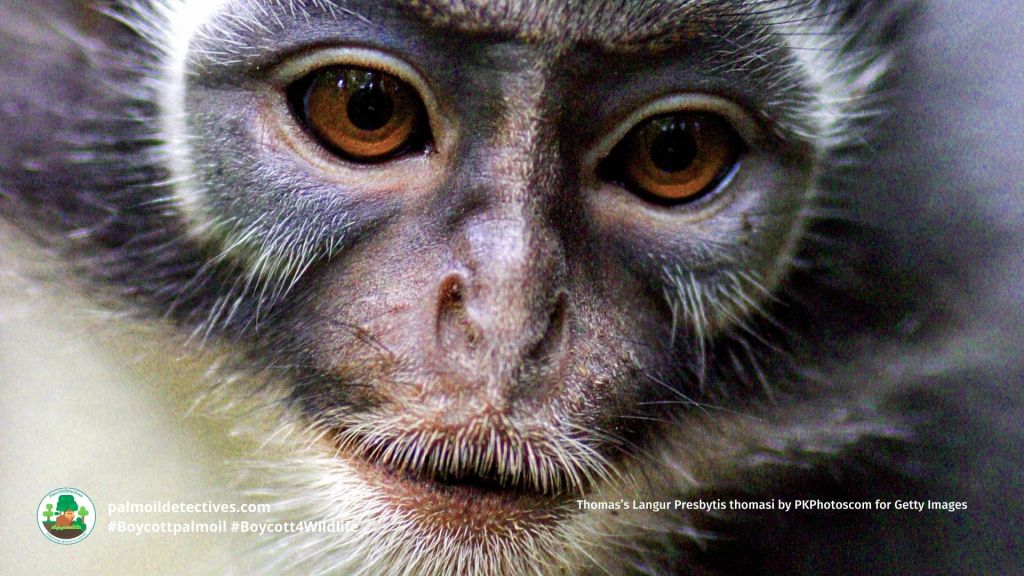

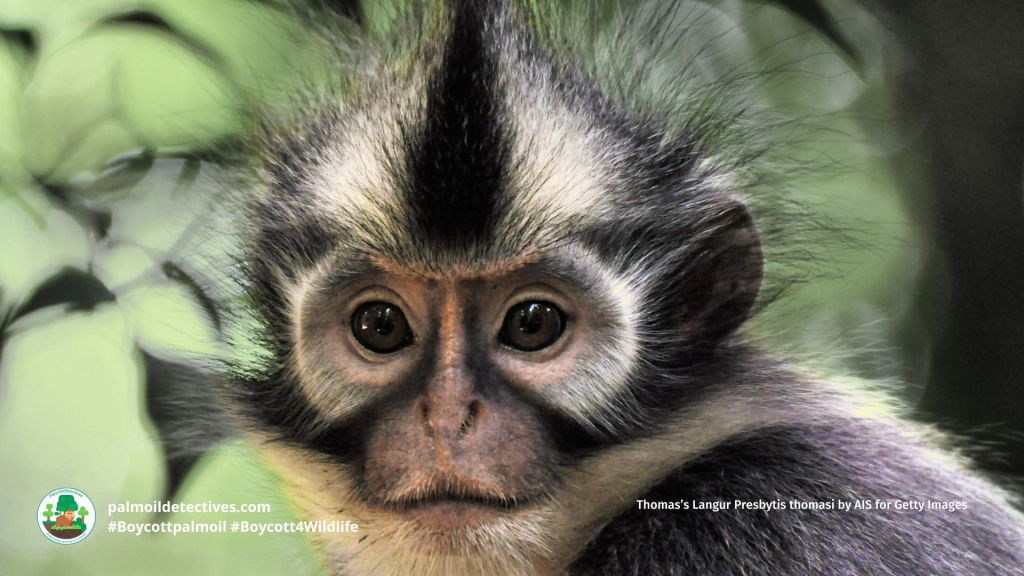

Thomas’s Langur is a small-bodied, highly distinctive primate. Their expressive amber eyes are framed by a whimsical ‘mohawk’ of fur – white at the front and dark grey along the midline – with flaring white cheek tufts giving them a perpetual look of surprise. Their back and limbs are grey, while the underparts are pure white, creating a dramatic contrast. Infants are born almost entirely white.

They live in social groups of 10–20 individuals and are arboreal, moving gracefully through the canopy. Though they are agile and peaceful, these monkeys are alert and cautious, especially in areas with higher predator or infanticide risk. They’ve been observed adjusting their vigilance levels depending on their location within the forest and the presence of neighbouring groups.

Diet

Thomas’s Langur is primarily folivorous, meaning their diet mainly consists of leaves. However, they also consume unripe fruit, flowers, toadstools, snails, and even rubber tree seeds when available. They have highly adapted digestive systems with gut microbes capable of breaking down cellulose, allowing them to extract nutrients from fibrous plant material. They tend to avoid ripe fruit, which could kill these microbes, and instead prefer high-pH, less acidic produce.

Reproduction and Mating

These langurs reach reproductive maturity around 5.4 years of age. The average interbirth interval is about 22 months, though this can vary depending on whether the previous infant survives. Females give birth to a single offspring at a time and care for them extensively. Infanticide by incoming males is a documented threat in overlapping territories, which may influence both vigilance and social dynamics within groups.

In the wild, Thomas’s Langurs live up to 20 years, with longevity extending to 29 years in captivity due to the absence of predators and reduced stress.

Geographic Range

Thomas’s Langur is restricted to northern Sumatra in Indonesia, primarily within Aceh Province. They are found north of the Alas (Simpangkiri) and Wampu Rivers, though newer records suggest they also exist just south of the Alas. Key populations reside in the Leuser Ecosystem, particularly around the Ketambe Research Station and Bukit Lawang in Gunung Leuser National Park. The species’ range is geographically fragmented by rivers and human activity.

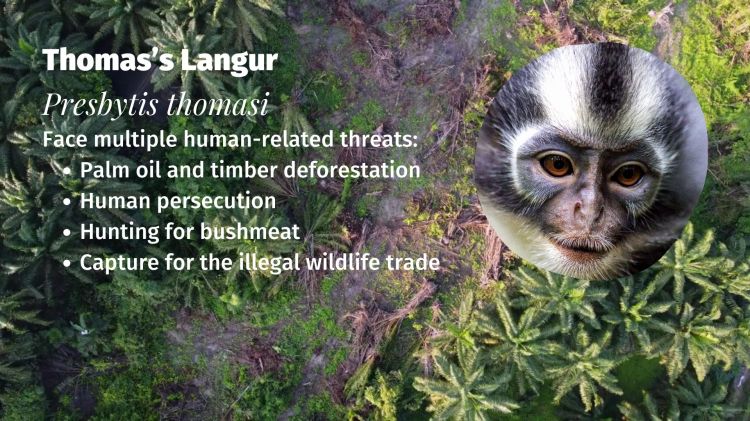

Threats

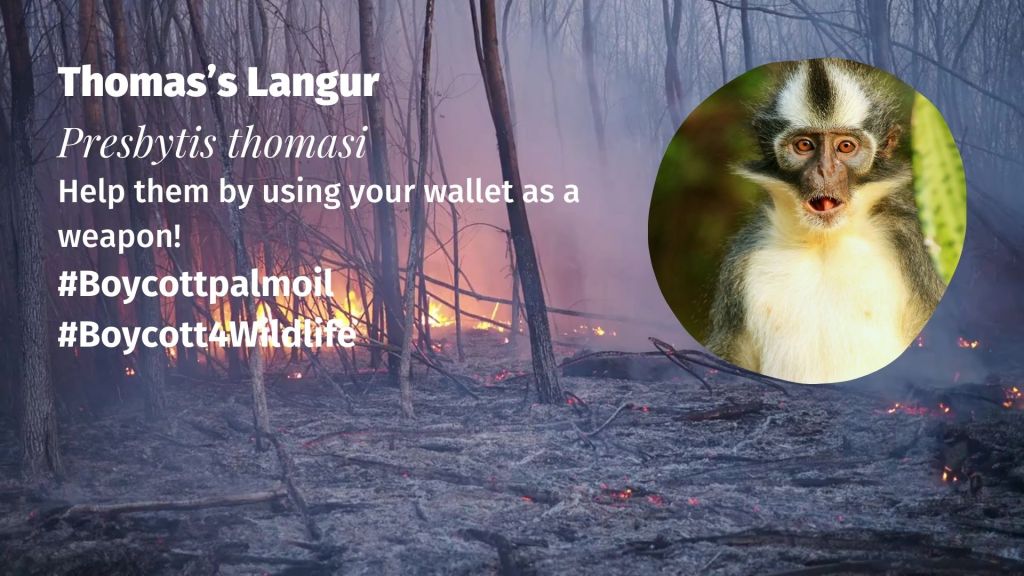

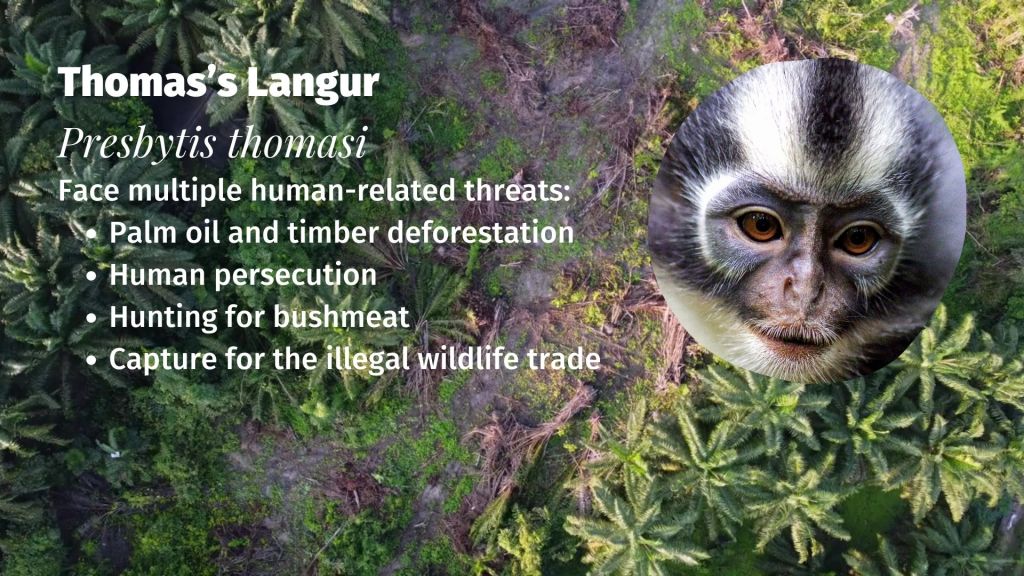

The species is considered Vulnerable due to past and continued population declines, estimated at more that 30% over the past 40 years (three generations) due to loss of habitat, especially to logging and oil palm plantations. Due to continuing threats, it is suspected to decline at the same rate over the next one generation.

IUCN Red List

• Palm oil and timber deforestation

Thomas’s langur faces severe habitat loss due to widespread deforestation in northern Sumatra. Logging operations, both legal and illegal, have cleared vast tracts of primary forest, fragmenting the langurs’ habitat and forcing them into smaller, isolated patches. The conversion of forests into oil palm plantations is accelerating this destruction, leading to population declines estimated at more than 30% over the past 40 years. This fragmentation not only reduces available food sources but also isolates groups, limiting genetic diversity and increasing the risk of local extinctions.

• Hunting and human persecution

Though protected by the local Batak traditional and religious taboos, there is some ‘marginal’ hunting pressure in the other parts of their distribution. The species is sometimes killed for bushmeat or captured for traditional medicine practices. In areas where these taboos are not observed, or where poverty drives people to seek alternative food sources, hunting pressure remains a real threat. Even low levels of hunting can have significant impacts on slow-reproducing primates like Thomas’s langur.

• Illegal Pet Trade

Infant langurs are often captured and sold in wildlife markets, especially in areas close to tourism hotspots like Bukit Lawang. To obtain a baby, adult females are usually killed, which has devastating consequences for troop dynamics and survival. Captive langurs often suffer from malnutrition, stress, and poor care, and rarely survive long in the pet trade. This exploitation is driving the species further toward extinction and contributes to the destruction of wild populations.

• Human-Wildlife Conflict

As forests are cleared, Thomas’s langurs increasingly move into croplands and plantations in search of food. This brings them into direct conflict with farmers, who may perceive them as pests and shoot them to protect crops. These retaliatory killings are not only cruel but contribute to the already rapid decline in population numbers. Furthermore, such conflicts reduce public tolerance for the species and hinder conservation efforts unless addressed through community engagement and education.

Take Action!

Thomas’s Langur is a symbol of Sumatra’s disappearing biodiversity. Protecting their habitat means preserving the rich web of life in which they play an essential role. You can make a difference, every time you shop #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife. Advocate for indigenous-led conservation in Sumatra and campaign against the illegal wildlife trade. Support plant-based agriculture and rewilding efforts. Go #Vegan #BoycottMeat

FAQs

How many Thomas’s Langurs are left in the wild?

Exact population estimates for the Thomas’s Langur are unknown, but data suggests that their numbers have declined by more than 30% in the past 40 years (three generations). This is largely due to habitat destruction and fragmentation (Wich et al., 2007).

How long do Thomas’s Langurs live?

In the wild, they typically live around 20 years. In captivity, individuals have been known to live up to 29 years (Wich et al., 2007).

Why are Thomas’s Langurs endangered?

The main threat is deforestation from logging and conversion of land into palm oil plantations. This leads to loss of their primary rainforest habitat and forces them into closer contact with humans, where they may be shot or captured for trade (IUCN, 2021).

Do Thomas’s Langurs make good pets?

Absolutely not. Keeping Thomas’s Langurs as pets is not only unethical but illegal. The illegal pet trade contributes directly to their decline, as infants are taken from their mothers, often involving violence. Supporting this trade fuels cruelty and threatens their survival. Advocate against the exotic pet trade instead.

Further Information

Setiawan, A. & Traeholt, C. 2020. Presbytis thomasi. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T18132A17954139. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T18132A17954139.en. Downloaded on 24 January 2021.

Ecology Asia. (n.d.). Thomas’s Leaf Monkey – Presbytis thomasi. Retrieved March 25, 2025, from https://www.ecologyasia.com/verts/mammals/thomas’s-leaf-monkey.htm

Sterck, E. H. M., Willems, E. P., van Schaik, C. P., & Wich, S. A. (2005). Demography and life history of Thomas langurs (Presbytis thomasi). American Journal of Primatology, 69(6), 641–651. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20386

Steenbeek, R., Piek, R. C., van Buul, M., & van Hooff, J. A. R. A. M. (1999). Vigilance in wild Thomas’s langurs (Presbytis thomasi): the importance of infanticide risk. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 45, 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002650050547

Wich, S. A., Steenbeek, R., Sterck, E. H. M., Korstjens, A. H., Willems, E. P., & van Schaik, C. P. (2007). Demography and life history of Thomas langurs (Presbytis thomasi). American Journal of Primatology, 69(6), 641–651. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20386

Wich, S. A., Schel, A. M., de Vries, H., & van Schaik, C. P. (2008). Geographic variation in Thomas Langur (Presbytis thomasi) loud calls. American Journal of Primatology, 70(6), 566–574. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ajp.20527

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Thomas’s langur. Wikipedia. Retrieved March 25, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas%27s_langur

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Discover more from Palm Oil Detectives

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.