Malayan Tapir Tapirus indicus

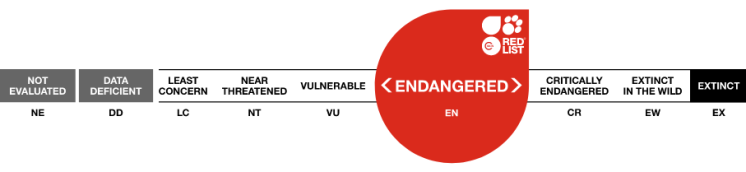

IUCN Red List Status: Endangered

Locations: Thailand, Myanmar, Peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra (Indonesia)

Found in tropical lowland and montane forests of Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula, with isolated populations in western Thailand and the Thai-Myanmar border region.

The Malay Tapir is listed as Endangered due to a severe and ongoing population decline of over 50% in the past 36 years. This is driven primarily by deforestation from palm oil expansion, fragmentation of habitat, road kills, and accidental deaths in illegal snares. Their forest homes are being rapidly replaced by palm oil monoculture plantations, especially in Sumatra and Malaysia, leaving fewer than 2,500 mature individuals in the wild. Despite being important seed dispersers in their ecosystem they face a dire future, particularly in Sumatra where remaining tapir populations are critically low and fragmented. Use your wallet as a weapon—#BoycottPalmOil and demand forest protection to stop the extinction of these elusive and important forest dwellers. #Boycott4Wildlife

Gentle Malayan #Tapirs are gorgeous creatures living in #Sumatra #Myanmar #Thailand #Indonesia they are endangered by #palmoil #deforestation. Say no to their #extinction when you shop #BoycottPalmOil 🌴🪔🤮💀🔥🙈🧐🚫 #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2021/02/05/malay-tapir-tapirus-indicus/

Baby Malayan #Tapirs have spotty coats to blend into the forests of #Malaysia 🇲🇾 #Indonesia 🇮🇩 They face big threats from #PalmOil #Ecocide and the illegal wildlife trade. Fight for them #BoycottPalmOil 🌴🪔🤮💀🔥🙈🧐🚫 #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2021/02/05/malay-tapir-tapirus-indicus/

Population declines are estimated to have been greater than 50% in the past three generations (36 years) driven primarily by large scale conversion of tapir habitat to palm oil plantations and other human dominated land-use. The main reason for declines in the past is habitat conversion, with large tracts land being converted into palm oil plantations. However, increasingly as other large ‘prey” species decline in the area hunters are beginning to look towards tapir as a food source.

iucn RED lIST

Appearance and Behaviour

The Malay Tapir, also known as the Asian Tapir, is instantly recognisable due to their striking black-and-white colouring—black at the front and back with a pale saddle across the midsection, a form of disruptive camouflage in low-light forest. They are the largest of the tapir species and the only one found in Asia. Solitary and nocturnal, Malay Tapirs are shy browsers that patrol large territories, communicating through high-pitched whistles and squeals. Recent studies have revealed they have individually distinct vocalisations, likely used for identification and social interactions in dense forest (Walb et al., 2021).

Diet

Malay Tapirs are generalist herbivores, browsing on more than 380 species of plants. They prefer young shoots, leaves, fruits, and twigs, often breaking branches to access foliage. Though not considered strong seed dispersers due to seed chewing, their selective feeding plays an important ecological role in maintaining forest structure.

Reproduction and Mating

Breeding is non-seasonal, with females giving birth to a single calf after an 11–13 month gestation. Calves are born with brown and white striped coats, providing excellent camouflage. They stay with their mother for up to two years. In captivity, a rare case of twin births has been documented, suggesting the potential for delayed implantation.

Geographic Range

Malay Tapirs are distributed in three main regions:

- Sumatra, Indonesia: Southern and central regions, with highly fragmented and declining populations.

- Peninsular Malaysia and Southern Thailand: This region supports the largest and most stable population, though southern forest fragments are facing increasing isolation.

- Thailand–Myanmar border: Populations here are small and fragmented, primarily surviving in transboundary protected areas such as the Western Forest Complex and Taninthayi Range. The species is presumed extinct in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam.

Threats

Palm oil deforestation

The conversion of lowland tropical rainforest into palm oil plantations remains the single largest threat to Malay Tapirs. Their preferred habitat—dense, moist forests—is being cleared at an alarming rate, particularly in Sumatra and Peninsular Malaysia. This habitat destruction not only reduces the available range but also isolates populations into small, disconnected forest fragments. These plantations also increase human-wildlife conflict and create ecological dead zones that offer no viable resources for tapirs to survive.

Habitat fragmentation and road kills

As forests are dissected by roads and settlements, Malay Tapirs are forced to cross dangerous terrain in search of food or mates. This leads to a growing number of road-related mortalities. In Malaysia alone, more than 50 displaced tapirs were recorded from 2011–2013, with a third of them killed by vehicles. These roads also hinder genetic flow between populations, worsening inbreeding risks and reducing overall population viability.

Illegal snaring and accidental trapping

Tapirs are often the unintended victims of wire snares set for other species. These traps are indiscriminate and deadly, frequently causing injuries or deaths. In Sumatra, tapirs have been killed or maimed by these snares, often set by local hunters targeting wild boar or deer. Although not the primary target, tapirs are especially vulnerable due to their large size and solitary movements through the forest.

Increased hunting pressure

While Malay Tapirs are traditionally not hunted in most of their range due to cultural taboos or lack of desirability as bushmeat, this is beginning to change. As populations of more desirable prey like deer decline, hunters are starting to target tapirs out of desperation. In some areas, such as Sumatra, tapir meat has been sold in local markets. There are also concerns that declining rhino populations may prompt poachers to kill tapirs and sell their body parts as ‘placebo rhino’.

Live capture and illegal wildlife trade

In Indonesia, the capture of tapirs for private collections and zoos was once common, with reports of dozens of animals passing through institutions like Pekanbaru Zoo since the 1990s. Although this trade has diminished in recent years, likely due to increased awareness and regulations, any resurgence in live capture—whether for display or illegal sale—would place enormous pressure on already fragile wild populations.

Inbreeding and isolation in small subpopulations

Many of the remaining tapir populations are isolated in small forest patches, especially in southern Peninsular Malaysia and parts of Thailand. Subpopulations often contain fewer than 15 individuals, far below the viable threshold for long-term survival. Without corridors or human-managed gene flow, these populations suffer from inbreeding, reduced fertility, and increased risk of extinction due to random events or disease.

Loss of salt lick access

Salt licks are vital for tapirs to supplement their mineral intake, especially in areas with a plant-based diet low in sodium. However, the loss of access to natural salt licks due to forest clearance, road construction, and plantation expansion has a direct impact on their health and social behaviours. In Malaysia’s Belum-Temengor Forest Complex, research shows tapirs rely heavily on these mineral sources, often revisiting them every few weeks. The loss of salt licks fragments their home ranges and reduces fitness.

Unprotected habitat in Myanmar

In Myanmar, where only around 5% of the land is protected, much of the tapir’s habitat lies outside conservation zones and is increasingly targeted for rubber and palm oil expansion. Civil unrest and land tenure disputes further complicate conservation efforts, limiting access for researchers and increasing the likelihood of habitat destruction. Even where tapirs are present, the lack of formal protection makes long-term survival uncertain.

FAQs

How many Malay Tapirs are left in the wild?

Current estimates suggest fewer than 2,500 mature individuals remain globally, with some subpopulations containing as few as 10–15 individuals (IUCN, 2017). Populations in Sumatra are estimated at fewer than 500 individuals and continue to decline due to deforestation and snaring.

What is the average lifespan of Malayan Tapirs?

In the wild, Malay Tapirs may live around 25–30 years. In captivity, they can exceed this range under veterinary care, though stress-related illnesses are common.

Are Malay Tapirs hunted?

Although not traditionally consumed in Malaysia or Thailand, tapirs are sometimes hunted for meat or mistaken for other animals. In some areas, displaced tapirs are also killed in retaliation after wandering into plantations or villages. Live trade for zoos and illegal private collections was once common, particularly in Indonesia, but this appears to have declined in recent years.

?Do Malay Tapirs make good pets?

Absolutely not. Keeping a Malay Tapir as a pet is incredibly cruel and illegal. These solitary forest dwellers are endangered and belong in their natural habitat – deep in the rainforest. Capturing or trading them for private ownership contributes directly to their extinction and causes immense suffering.

Why are salt licks important to Malayan Tapirs?

Recent studies have shown that Malay Tapirs frequently visit salt licks to supplement their diet with essential minerals. These areas may also serve social functions, where male and female tapirs overlap and interact (Tawa et al., 2021).

Take Action!

- Boycott all products containing palm oil every time you shop. Learn how.

- Support rewilding and indigenous-led conservation efforts in Southeast Asia.

- Campaign for forest protection policies across Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia.

- Demand accountability from zoos and wildlife traffickers involved in the live trade of endangered animals.

- #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife Go #Vegan and #BoycottMeat

Further Information

Pinondang, I. M. R., Deere, N. J., Voigt, M., Ardiantiono, Subagyo, A., Moßbrucker, A., … Struebig, M. J. (2024). Safeguarding Asian tapir habitat in Sumatra, Indonesia. Oryx, 58(4), 451–461. doi:10.1017/S0030605323001576

Tawa, Y., Mohd Sah, S. A., & Kohshima, S. (2021). Salt-lick use by wild Malayan tapirs (Tapirus indicus): Behaviour and social interactions at salt licks. European Journal of Wildlife Research, 67, 91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-021-01536-9

Traeholt, C., Novarino, W., bin Saaban, S., Shwe, N.M., Lynam, A., Zainuddin, Z., Simpson, B. & bin Mohd, S. 2016. Tapirus indicus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T21472A45173636. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T21472A45173636.en. Downloaded on 04 February 2021.

Walb, R., von Fersen, L., Meijer, T., & Hammerschmidt, K. (2021). Individual Differences in the Vocal Communication of Malayan Tapirs (Tapirus indicus) Considering Familiarity and Relatedness. Animals, 11(4), 1026. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11041026

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Discover more from Palm Oil Detectives

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.