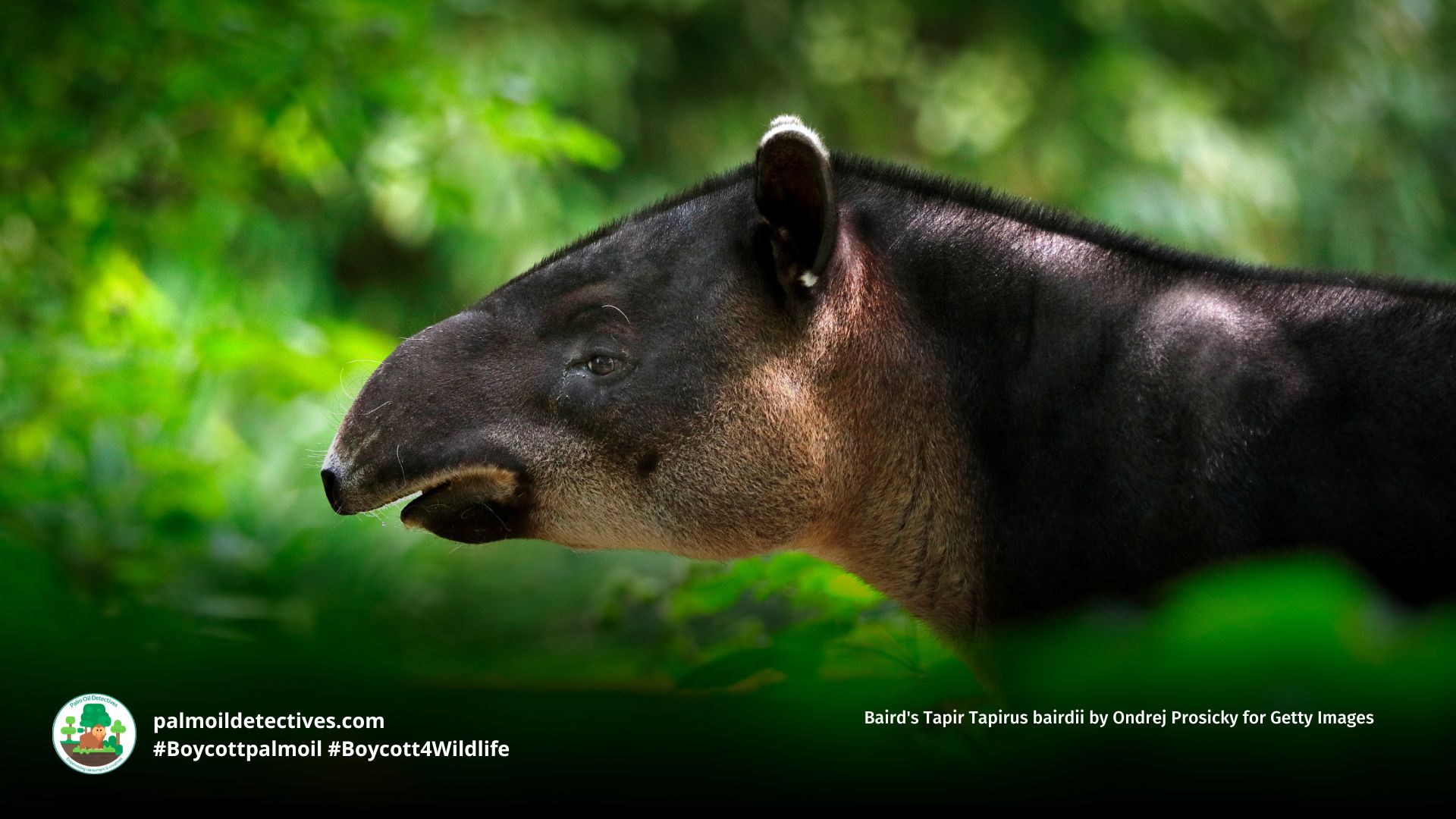

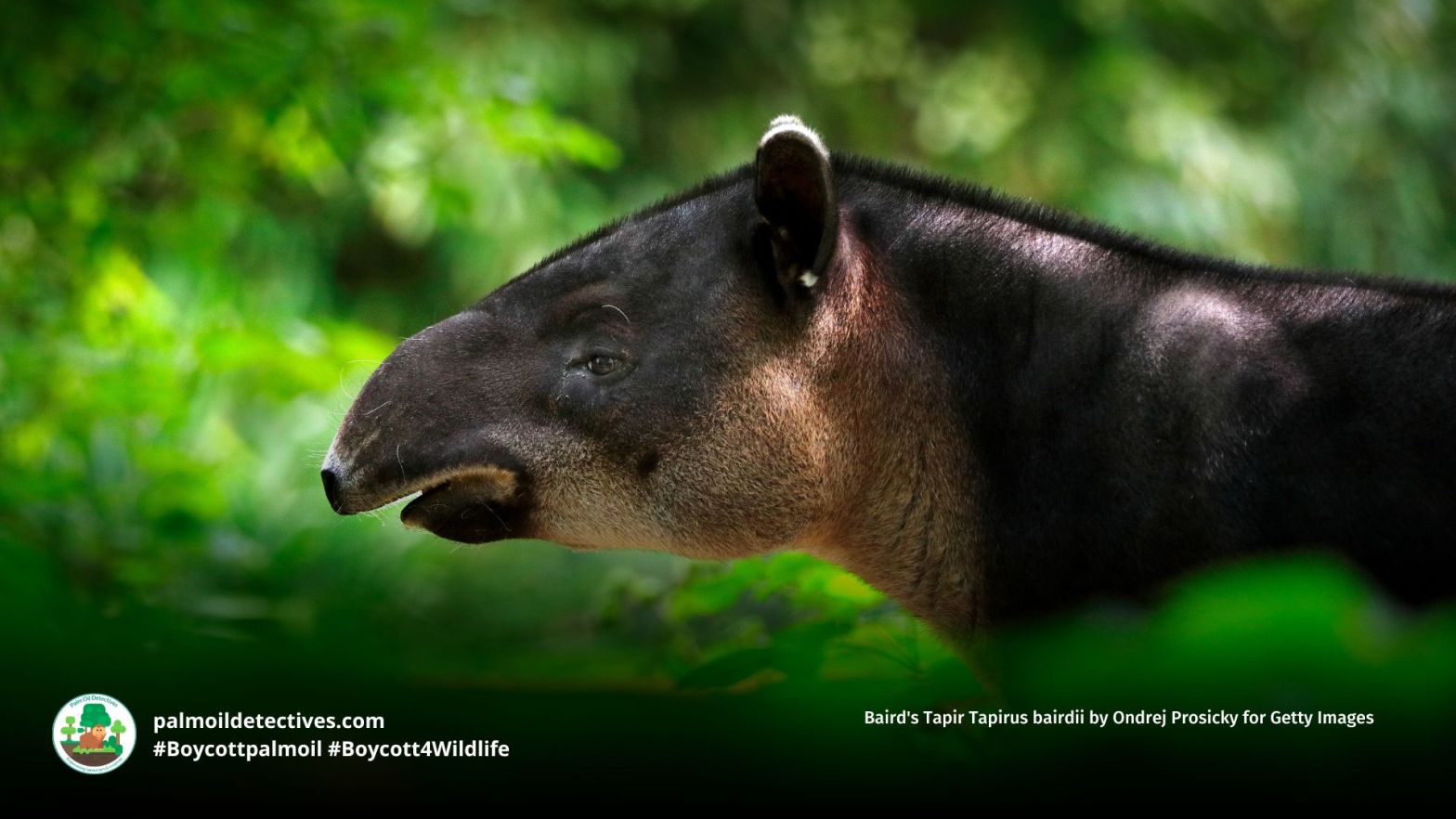

Baird’s Tapir Tapirus bairdii

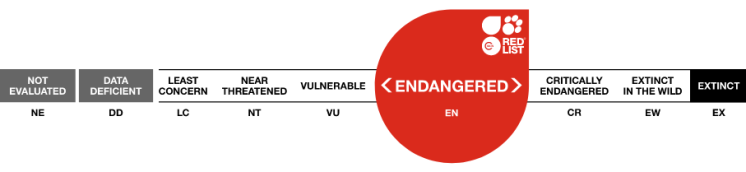

Endangered

Extant (resident): Belize; Colombia; Costa Rica; Guatemala; Honduras; Mexico; Nicaragua; Panama

Extinct: El Salvador

Presence Uncertain: Ecuador

Baird’s tapirs may look like they are relatives of elephants, but they’re actually closer kin to horses, donkeys, zebras, and rhinoceroses. Also known as the Central American tapir, they are the largest land mammals in Central America and a living relic of an ancient lineage.

Their robust, stocky bodies and distinctive trunk-like snout make them unique among mammals. However, they are now Endangered, with fewer than 5,000 individuals left in the wild.

Tragically, palm oil, soy and meat deforestation, hunting, and human encroachment are driving this species toward extinction. Protecting their habitats is critical to ensuring their survival. Use your wallet as a weapon—boycott palm oil and support conservation initiatives. #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife

Even though they look like elephants 🐘 Baird’s Tapirs are more closely related to #horses 🐴 and #rhinos 🦏🩶 #Endangered in #SouthAmerica from #palmoil 🌴🥩🔥 #meat #deforestation. Help save them! Be #vegan and #Boycottpalmoil @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2021/06/26/bairds-tapir-tapirus-bairdii/

Weighing up to 300kg and 2 metres in length the Baird’s Tapir is a gentle giant #ungulate of #Guatemala 🇬🇹#Mexico 🇲🇽 #Colombia 🇨🇴 #Palmoil #deforestation and #hunting are threats. Help them to survive, be #vegan and #Boycottpalmoil 🌴🪔⛔️ @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2021/06/26/bairds-tapir-tapirus-bairdii/

Appearance and Behaviour

Baird’s tapirs are large, herbivorous mammals weighing between 200–300 kg and reaching up to 2 metres in length. Their short, bristly coat is dark brown, with a distinctive cream-coloured patch running from their cheeks to the tip of their rounded ears. They also have small, expressive eyes and a prehensile snout used for foraging.

Like all tapirs, this species has a prominent nose. This is made of soft and flexible tissues, allowing them to snatch leaves and stems that would otherwise be out of reach. This species eats more than 200 kinds of plants, including twigs, stems, leaves, and even aquatic vegetation.

Baird’s Tapirs are solitary animals that usually only come together when they mate. Females have a gestation period of 13 months and then the baby remains with mum for 1-2 years. Juvenile Baird’s Tapirs have a coat covered in spots and tripes, that is thought to disguise them from predators such as Jaguars and Pumas in the understory of the rainforest.

Despite their size, tapirs are shy and elusive, often active at night (nocturnal) or during twilight hours (crepuscular). They are excellent swimmers, using rivers and lakes as escape routes from predators and to cool down in tropical heat. Tapirs are highly territorial and mark their paths with urine trails.

Threats

IUCN Status: Endangered

Habitat Destruction: Deforestation for palm oil and soy agriculture, livestock grazing, along with palm oil and soy monoculture plantations has led to an 85% reduction in Baird’s tapir habitats. In Central America, critical lowland forests are being cleared at an alarming rate.

Infrastructure development: Such as roads and dams, fragments their habitats, isolating populations.

Hunting: Tapirs are often hunted for their meat, despite legal protections in many countries.

Climate Change: Shifting rainfall patterns and rising temperatures from climate change threaten the tropical ecosystems tapirs rely on. Increased frequency of droughts and floods reduces access to food and shelter.

Human-Wildlife Conflict: As human settlements expand, tapirs often wander into agricultural lands, where they are killed to protect crops.

Geographic Range

Baird’s tapirs are found in the tropical forests of Mexico and Central America, including Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Panama. They are also present in small numbers in Colombia. They inhabit lowland rainforests, mangroves, and montane forests up to elevations of 3,000 metres.

Populations are most stable in protected areas, such as Costa Rica’s Corcovado National Park and Panama’s Darien National Park. However, even these areas are not immune to deforestation and poaching.

Diet

Tapirs are herbivorous browsers, consuming over 200 plant species, including fruits, leaves, twigs, and aquatic vegetation. Their strong prehensile snouts allow them to grasp and pull vegetation with precision. As seed dispersers, they play a critical role in forest regeneration by spreading seeds through their dung over vast areas.

The loss of diverse tropical forests reduces food availability and puts additional pressure on declining populations.

Reproduction and Mating

Baird’s tapirs have a long gestation period of approximately 13 months, after which a single calf is born. Calves weigh about 10 kg at birth and are covered in light spots and stripes for camouflage. These markings fade as they grow.

Females typically give birth every 2–3 years, which limits population recovery. Young tapirs stay with their mothers for up to two years before becoming independent. Habitat loss and hunting reduce their chances of surviving to adulthood.

Take Action!

The survival of Baird’s tapirs is in your hands. Support indigenous-led conservation efforts, boycott palm oil, and spread awareness of their plight. Together, we can fight for their survival. #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife

FAQ

How many Baird’s tapirs are left in the world?

Fewer than 5,000 mature individuals remain, with populations declining rapidly due to habitat loss and poaching.

What is the closest relative to the Baird’s tapir?

Baird’s tapirs are most closely related to other members of the Tapiridae family, such as the South American tapir (Tapirus terrestris) and the Malayan tapir (Tapirus indicus).

Is a tapir a pig or elephant?

Neither. Tapirs are perissodactyls (odd-toed ungulates) and are more closely related to horses and rhinoceroses than pigs or elephants.

Where do Baird’s tapirs live?

They inhabit tropical and subtropical forests in Central America, including Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Panama.

What’s the biggest threat to the Baird’s tapir?

Between 2001 and 2010, Mexico and Central America lost 179,405 km² of forest, replaced by palm oil plantations and agricultural land. The Maya Forest in Mexico, Belize, and Guatemala, as well as Nicaragua’s Caribbean coast, faced the highest deforestation rates (Aide et al., 2012). This deforestation fragments habitats, isolating tapir populations genetically. In Nicaragua, even Biosphere Reserves and protected areas are under severe threat from ongoing deforestation.

In recent years, the increasing of palm oil plantations through the Baird Tapir’s distribution is becoming an relevant threat in the region.

IUCN red list

You can support this beautiful animal

There are no known conservation activities for this animal. Share out this post to social media and join the #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife on social media to raise awareness

Further Information

Castellanos, A., et al. (2023). Baird’s Tapir Conservation. ScienceDirect.

Garcìa, M., Jordan, C., O’Farril, G., Poot, C., Meyer, N., Estrada, N., Leonardo, R., Naranjo, E., Simons, Á., Herrera, A., Urgilés, C., Schank, C., Boshoff, L. & Ruiz-Galeano, M. 2016. Tapirus bairdii. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T21471A45173340. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T21471A45173340.en. Downloaded on 06 June 2021.

EDGE of Existence. (2023). Baird’s Tapir. EDGE of Existence.

National Geographic. (2021). Baird’s Tapir. National Geographic.

Reuben-Crane, A., et al. (2012). Elevational Distribution and Abundance of Baird’s Tapir in Talamanca Region of Costa Rica. ResearchGate.

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Discover more from Palm Oil Detectives

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Really appreciate it

LikeLike