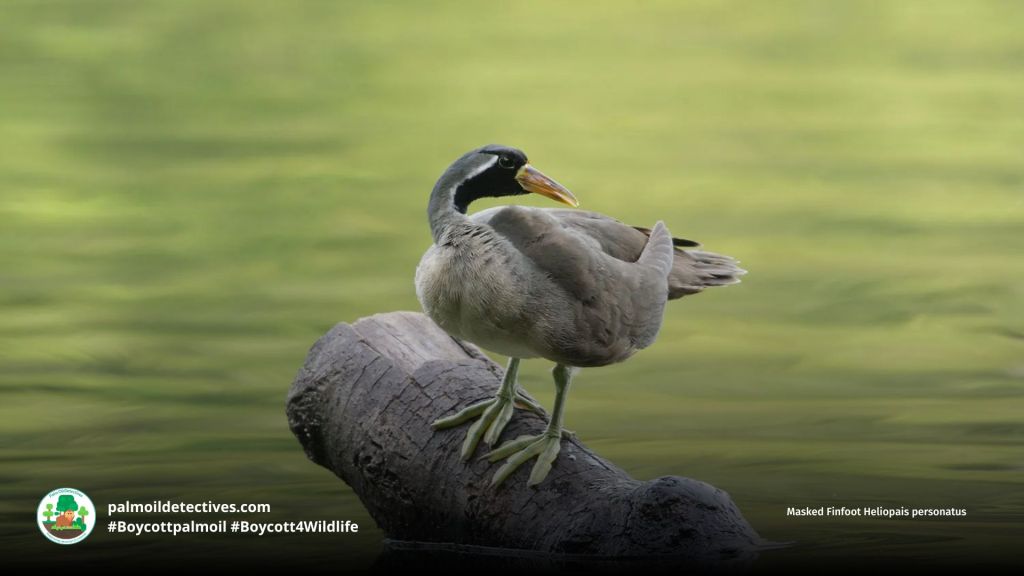

Masked Finfoot Heliopais personatus

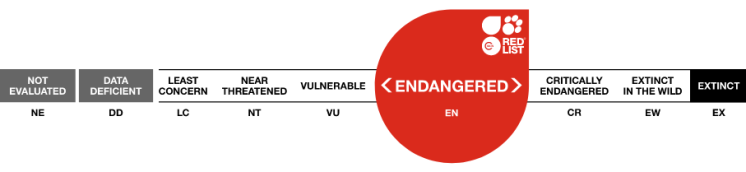

IUCN Status: Critically Endangered

Location: Bangladesh, Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia (Now extinct), India (now extinct)

The masked finfoot is vanishing before our eyes. Once widespread across South and #SoutheastAsia, fewer than 300 individuals remain alive. Their numbers are in freefall due to habitat destruction, rampant palm oil expansion, hydropower projects, and human disturbance (Chowdhury et al., 2020). These rare and secretive #waterbirds, with their striking black masks and vivid green lobed feet, are slipping towards #extinction.

These #birds were once found in the dense, shadowy mangroves and riverine forests from #India to #Indonesia, their final strongholds are in Bangladesh and #Cambodia. Even there, unchecked deforestation and wetland clearance threaten their survival. Conservationists warn that without urgent intervention, this species could become Asia’s next avian extinction.

Protecting the masked finfoot means protecting their vanishing wetland homes. Boycott palm oil, support wetland conservation, and demand stronger protections for Southeast Asia’s last riverine forests. Help them every time you shop and #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife

Already #extinct in #Malaysia 🇲🇾 #India 🇮🇳 #Indonesia 🇮🇩 the Masked Finfoot is a unique #bird 🪿🩷 with unusual feet. #PalmOil #deforestation is a major threat. Help them when you #BoycottPalmOil 🌴🪔☠️🤢🔥🧐🙊⛔️ #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2021/02/05/masked-finfoot-heliopais-personatus

Appearance and Behaviour

The masked finfoot is a medium-sized aquatic bird with a long, elegant neck, vivid green lobed feet, and a sharp, pointed beak. Their dramatic black facial mask is offset by a white eyering and lateral stripe along the neck. Their back and wings are deep chestnut brown, contrasting with a pale underbelly. Males have an entirely black chin, while females have a distinctive white chin patch.

This species moves through the water with effortless grace, gliding silently through dense mangroves and forested waterways. Unlike grebes and ducks, they are not strictly aquatic—often foraging along riverbanks for fish, crustaceans, and insects. Their lobed feet, highly adapted for both swimming and gripping wetland vegetation, allow them to navigate both water and land with ease.

Geographic Range

The main threat is the destruction and increased levels of disturbance to rivers in lowland riverine forest, driven by agricultural clearance and logging operations and increased traffic on waterways.

IUCN Red list

The masked finfoot once thrived across South and Southeast Asia, from northeast India to Indonesia. Today, their range has collapsed. The most recent global population estimate suggests only 108 to 304 individuals remain (Chowdhury et al., 2020), with confirmed breeding populations only in Bangladesh and Cambodia. Once-regular sightings in Malaysia and Thailand have all but disappeared.

Myanmar may still hold small, unrecorded populations, but large-scale deforestation and wetland destruction mean that their future there is uncertain. The species has already been wiped out from large parts of its former range. Without urgent conservation action, they may soon disappear entirely.

Diet

The masked finfoot is an opportunistic feeder, preying on a variety of aquatic and terrestrial species. Their diet consists of freshwater shrimp, large beetles, small fish, dragonfly larvae, molluscs, and amphibians. They forage both in the water and along riverbanks, gleaning insects from overhanging vegetation or catching prey just below the surface. Their lobed feet allow them to navigate both aquatic and terrestrial environments with ease.

Reproduction and Mating

Little is known about the breeding biology of the masked finfoot due to their elusive nature. Their breeding season appears to coincide with the rainy season, from June to September in Bangladesh. They construct nests low above the water, using small sticks and reeds to form a platform. Clutch sizes range from three to seven eggs, and chicks hatch covered in dark grey down with a distinctive white spot on the tip of the beak. The young leave the nest shortly after hatching, though they remain dependent on their parents for food and protection.

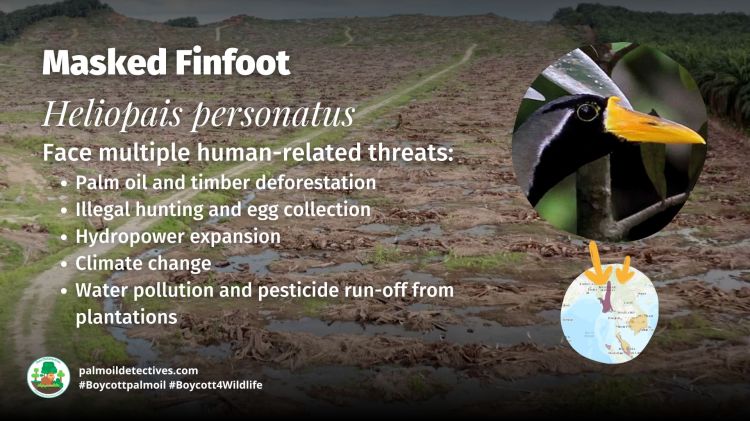

Threats

Kalimantan lost nearly 25% of its evergreen forest during 1985-1997. The impact of the major fires of 1997-1998 was patchy, with many small alluvial areas escaping damage(Fredriksson and Nijman 2004). However, such fires appear to be increasing in frequency and severity. In central Kalimantan, most remaining lowland forest is granted to logging concessions, with a negligible area currently afforded any protected status. The species was recorded in trade by TRAFFIC in 1998 when six birds were taken out of Kalimantan to Singapore(Shepherd 2000).

IUCN REd LIST

The masked finfoot faces multiple threats that have driven them to the brink of extinction.

Habitat Destruction and Palm Oil Plantations

• Lowland riverine forests are being cleared for palm oil plantations, rice fields, and other agricultural developments.

• Mangroves and wetland habitats are being drained and converted, destroying key breeding and foraging sites.

Habitat loss is the most significant driver of the masked finfoot’s decline. Without intact, undisturbed wetlands, their populations will continue to plummet.

Hydropower and Waterway Disruptions

• The construction of dams and hydropower projects alters water flow, reduces fish populations, and floods nesting sites.

• Increased boat traffic disturbs the birds and leads to habitat fragmentation.

Dams and river modifications disrupt the delicate ecosystems masked finfoots depend on, cutting them off from food sources and safe nesting sites.

Illegal Hunting and Egg Collection

• Although not a primary target for hunters, masked finfoots are occasionally hunted for food or captured opportunistically.

• Fishermen have reported taking eggs or chicks when they encounter nests.

With such a small population left, even occasional hunting and egg collection could have devastating consequences.

Climate Change and Rising Sea Levels

• Increased saltwater intrusion into wetland habitats threatens nesting trees and freshwater food sources.

• More frequent tropical storms and cyclones destroy nests and disrupt breeding seasons.

The Sundarbans population is particularly vulnerable, as climate change intensifies the frequency of severe weather events.

Pollution and Fishing Practices

• Oil spills, industrial pollution, and pesticide runoff poison water sources.

• The birds are at risk of entanglement in fishing nets, particularly in the Sundarbans.

Pollution and bycatch threaten not only the masked finfoot but many other wetland species that rely on clean rivers and estuaries.

Take Action!

The masked finfoot is on the edge of extinction. Choose 100% palm oil-free products, support wetland restoration, and demand stronger legal protections for their remaining habitats. Every decision you make as a consumer can help safeguard the future of this critically endangered species. #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife

FAQs

How many masked finfoots are left?

The global population is estimated to be between 108 and 304 individuals, far lower than the 600–1,700 estimate in 2009 (Chowdhury et al., 2020). With such a sharp decline, immediate conservation efforts are needed to prevent their extinction.

Where do masked finfoots live?

Historically, they were found across South and Southeast Asia. Today, breeding populations are confirmed only in Bangladesh and Cambodia. Myanmar may still have small, unrecorded populations, but the species has likely been extirpated from Malaysia and Thailand.

Why is the masked finfoot endangered?

Habitat destruction, palm oil plantations, hydropower development, hunting, and climate change are the biggest threats. Wetland clearance and deforestation have left them with almost nowhere to breed and forage.

How can we save the masked finfoot?

Boycotting palm oil, supporting wetland conservation projects, and advocating for stronger environmental protections are critical steps. Protected areas must be established, and existing habitats must be restored.

What do masked finfoots eat?

Their diet includes freshwater shrimp, insects, fish, and crustaceans. They hunt both in the water and along the riverbanks, using their lobed feet to navigate different environments.

Further Information

BirdLife International. 2016. Heliopais personatus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22692181A93340327. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22692181A93340327.en. Downloaded on 05 February 2021.

Chowdhury, S. U., Yong, D. L., Round, P. D., Mahood, S., Tizard, R., & Eames, J. C. (2020). The status and distribution of the masked finfoot Heliopais personatus—Asia’s next avian extinction? Forktail, 36, 16–24. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349094908_The_status_and_distribution_of_the_Masked_Finfoot_Heliopais_personatus-Asia’s_next_avian_extinction

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d). Masked finfoot. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved March 13, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Masked_finfoot

Support the conservation of this species

This animal has no protections in place. Read about other forgotten species here. Create art to support this forgotten animal or raise awareness about them by sharing this post and using the #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife hashtags on social media. Also you can boycott palm oil in the supermarket.

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Discover more from Palm Oil Detectives

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.