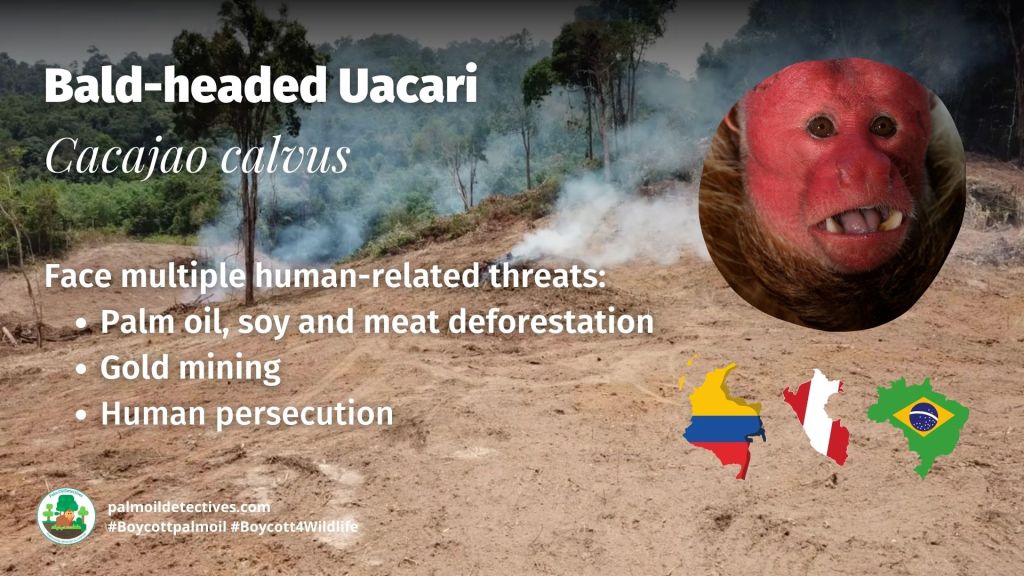

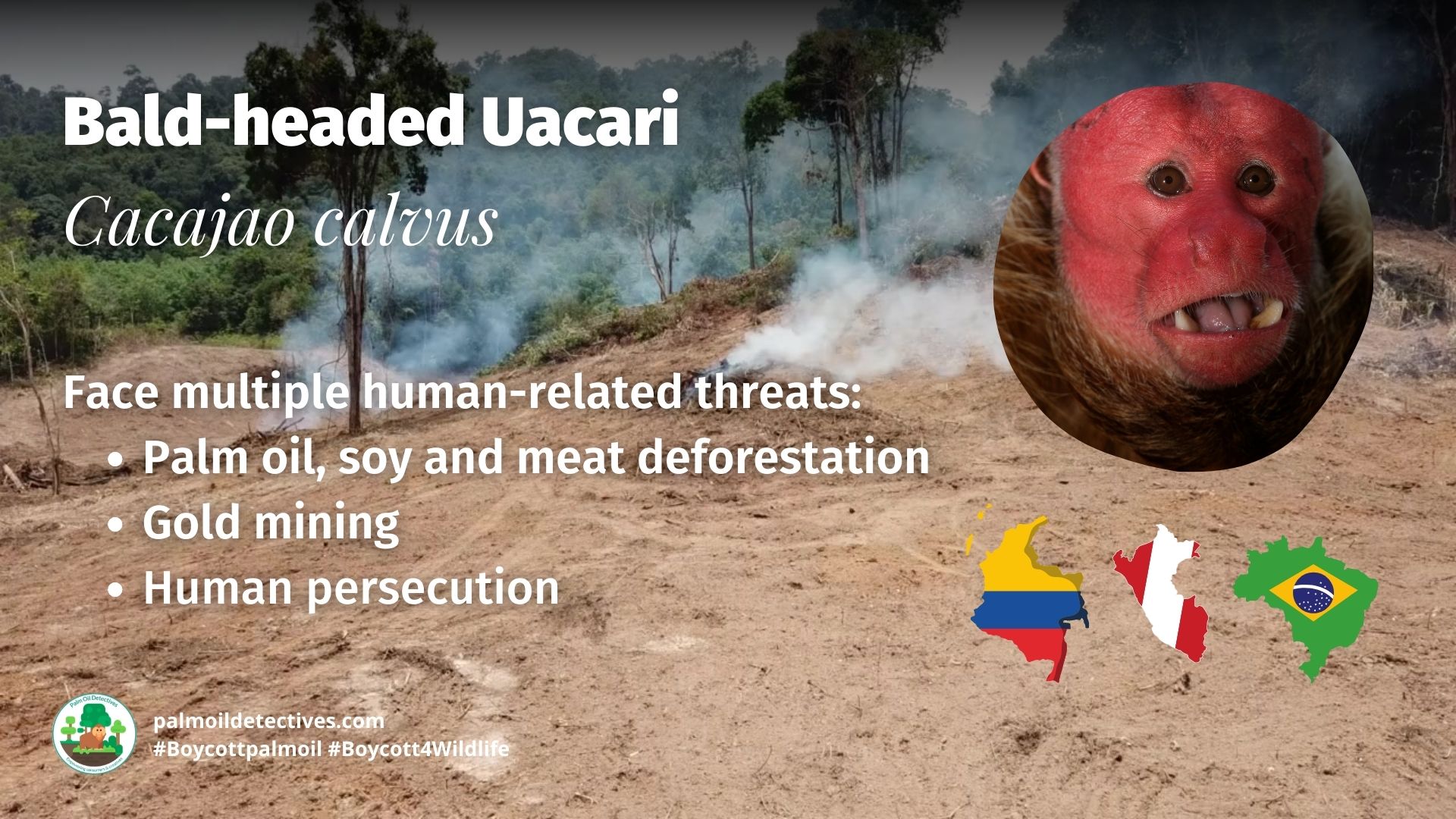

Bald-headed Uacari Cacajao calvus

Vulnerable

Brazil, Peru, Colombia

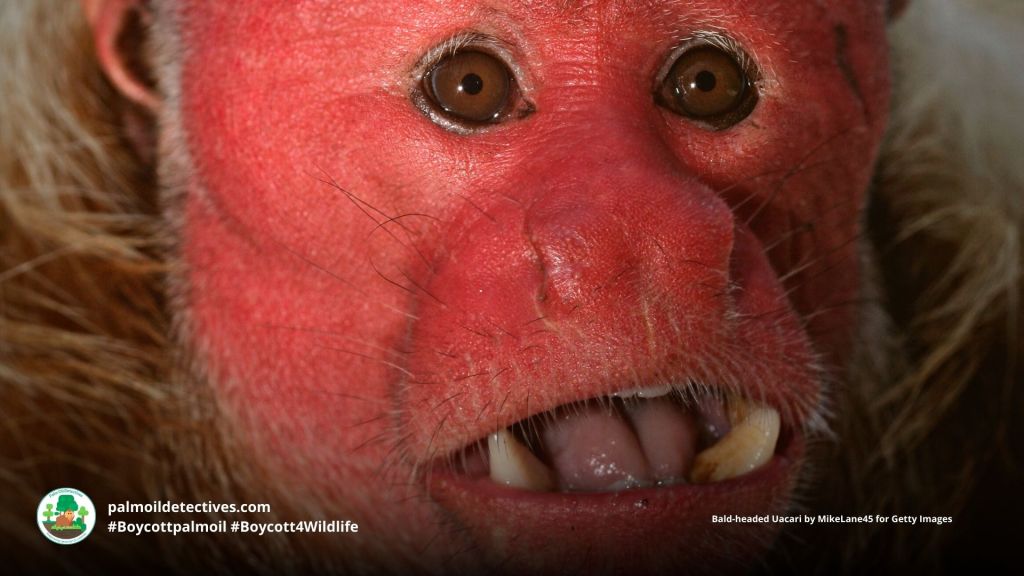

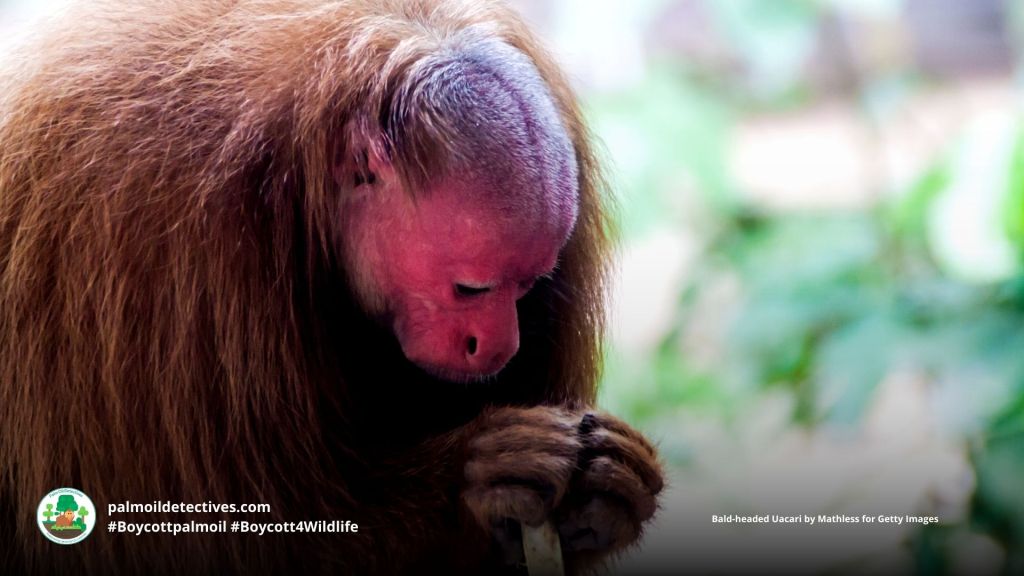

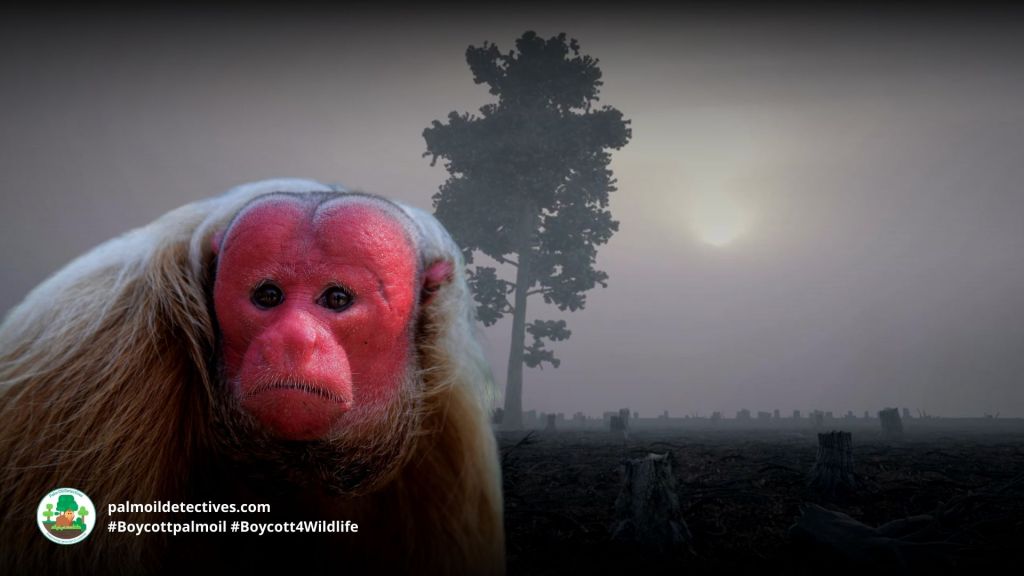

With their long shaggy coats and striking bright red faces, Bald-headed Uacaris are true icons of the Amazon rainforest and are found in #Brazil, #Peru and #Colombia. When a #Uacari has a bright red face this indicates they are in good health. A pale face indicates a sickly physical state. These remarkable #monkeys spend most of the year in the tree tops to avoid the seasonal flooding of their Amazonian habitat. During the dry season, they return to the ground to look for seeds. They face an existential threat from #palmoil, #soy and #meat #deforestation in the #Amazon. Once their unmistakeable scarlet faces were a common sight in the dusky green of the rainforest. Now they are rapidly disappearing, victims of a relentless drive for land, gold, and profit. Listed as Vulnerable, you can help them to survive every time you shop! #BoycottGold be #vegan for them and #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife

A stunning bright red face and shaggy coat give the Bald-headed Uacari a fairytale quality. They live in #Peru #Brazil and #Colombia in the #Amazon, threats incl. #palmoil #meat and #soy #deforestation. Take action! #Boycott4Wildlife https://palmoildetectives.com/2021/02/24/bald-headed-uacari-cacajao-calvus/ @palmoildetect

Uniquely beautiful Bald-headed Uacaris are unusual with their bright red faces. Threats include #palmoil #meat #soy and gold #mining #deforestation. Fight for their survival and #BoycottPalmOil and #gold! #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect.bsky.social https://palmoildetectives.com/2021/02/24/bald-headed-uacari-cacajao-calvus

Unfortunately, low birth rates, habitat destruction and deforestation all threaten the existence of the bald uacari.

national Geographic

Appearance and Behaviour

The Bald-headed Uacari is one of the most striking and easily recognisable primates of the Amazon Basin. Their vivid scarlet faces, completely free of fur, contrast sharply with their thick, shaggy coats. Scientific studies have shown that their red faces come from having very thin skin with a dense network of blood vessels just beneath the surface. Unlike other primates, they lack melanin pigment in their facial skin, allowing the redness to shine through. The bright red colour is thought to signal good health — individuals suffering from illness or parasites tend to have pale faces. This striking feature likely plays a major role in their social interactions and may help individuals choose healthy mates (Mayor et al., 2015).

Their long coats vary between subspecies, adding further distinction to their already dramatic appearance:

- Cacajao calvus calvus — Known as the White Bald-headed Uacari, this subspecies has a pale blonde to white coat, making their deep red faces even more prominent. They are found mainly around the Mamirauá Sustainable Development Reserve in Brazil.

- Cacajao calvus rubicundus — These Uacaris have reddish fur and pinkish-red faces, although little is known about their full physical description due to a lack of field studies.

- Cacajao calvus ucayalii — Also called the Peruvian Red Uacari, they have reddish-brown fur with a deep red face. Adults, particularly males, are heavier and have strong jaws adapted for cracking open very hard seeds.

- Cacajao calvus novaesi — This subspecies is poorly studied but is believed to have features that are somewhere between the pale calvus and the red ucayalii subspecies.

Bald-headed Uacaris are highly agile, moving quickly through the flooded forests and treetops. They have long limbs and strong hands that help them leap across branches, an essential skill during the rainy season when the forests are submerged and dry land disappears.

These New World monkeys are very gregarious and social, they live in groups called troops of close to 100 individuals. They then split up into smaller groups of about ten monkeys to forage. At night they sleep aloft, high in the rain forest canopy.

Groups of monkeys often split into smaller bands that travel separately and come back together depending on the season and food availability — a system known as “fission-fusion.” Some researchers believe Bald-headed Uacaris might even have complex social structures like those seen in some Old World monkeys, forming smaller family groups within larger communities (Bowler et al., 2012).

Diet

Bald-headed Uacaris have very specialised eating habits. They mostly eat the seeds inside fruits — not just soft fruit pulp like many other monkeys. Using their strong jaws and specialised teeth, they crack open hard seeds that other animals cannot access. In simple terms, they are seed specialists: animals that eat seeds as their main food. This unusual diet makes them important for forest health because they help control which plants grow by deciding which seeds get eaten and which survive. However, this also means they are vulnerable if their favourite trees are lost or their habitat changes.

Threats

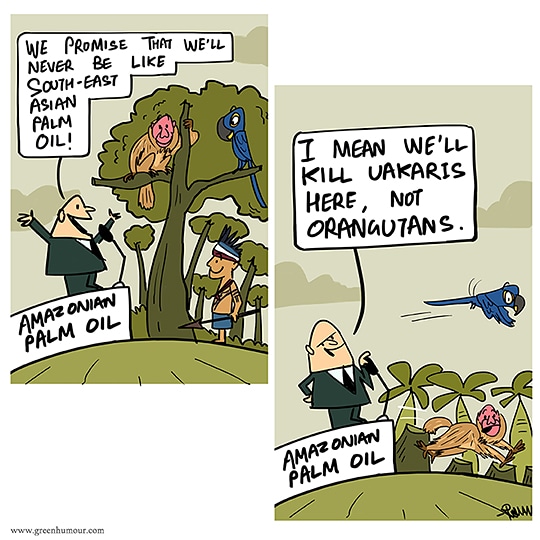

Palm oil, soy and meat deforestation

The greatest threat facing the Bald-headed Uacari is the relentless destruction of their várzea forest habitats. These flooded forests are systematically cleared for agriculture and pasture, often to make way for cattle ranching, along with soy and palm oil industrial crops.

Small-scale farmers cut and burn sections of forest along the Amazon’s tributaries, degrading critical habitat needed by the Uacaris to forage and move. Although Cacajao calvus calvus populations in protected areas like Mamirauá have remained relatively stable, forest cover in unprotected areas of Brazil and Peru is shrinking at alarming rates. Should current deforestation trends continue, an estimated 10–15% of their habitat could be lost by mid-century (Global Forest Watch, 2024). This loss is particularly devastating because Bald-headed Uacaris are habitat specialists, dependent on seasonal floodplain forests — ecosystems that cannot easily regenerate once destroyed. As a result, deforestation not only reduces the total area available but also fragments populations, leading to genetic isolation and making them more vulnerable to extinction.

Palm oil plantations are rapidly spreading in parts of the Amazon, especially in Brazil, Venezuela and Peru, where industrial palm oil production has increased dramatically in recent years. Clearing forests for palm oil destroys the complex ecosystems that Bald-headed Uacaris depend on and creates long-term environmental damage by draining swamps and altering flood cycles.

Gold mining

Illegal and industrial gold mining is another grave threat to the Amazon and the wildlife that lives there. Mining operations clear vast tracts of forest, pollute rivers with toxic mercury, and destroy the delicate floodplain ecosystems that Bald-headed Uacaris need to survive. Mercury used in gold extraction contaminates water systems, poisoning fish and other aquatic life, and eventually enters the food chain. Even low levels of mercury exposure can cause long-term harm to primates, including neurological damage and reproductive problems.

Gold mining also brings waves of human migration into remote forest areas, increasing deforestation and hunting. Rivers once teeming with life become muddy, barren channels, while forests are left pockmarked with scars from mining pits. For Bald-headed Uacaris, whose lives are so closely tied to the health of river systems and floodplain forests, gold mining represents a direct assault on their habitat and wellbeing. Without urgent action to curb mining activities, these ecosystems — and the species that depend on them — face an uncertain future.

Hunting

Hunting is a significant threat to the Bald-headed Uacari, particularly in areas outside protected reserves. In some regions, they are hunted for bushmeat, despite their human-like appearance, which in a few traditional cultures discourages killing. In Peru, particularly along the Ucayali and Yavarí rivers, surveys have shown that hunting has already exterminated Uacari populations from entire stretches of their historical range (Aquino, 1988). The rise of logging operations in these remote areas has further exacerbated the problem. New logging roads provide easier access for hunters, and increased human presence fuels the demand for bushmeat. On the Yavarí and Yavarí-Mirín rivers, hunting levels rose sharply after 2004, correlating with the arrival of logging companies (Bodmer et al., 2006). This expansion has turned once-inaccessible refuges into open hunting grounds, severely threatening remaining Uacari populations.

Competition for aguaje palm with humans

The Mauritia flexuosa palm, also known as the aguaje palm, is a key food resource for the Bald-headed Uacari, particularly for the Cacajao calvus ucayalii subspecies. However, unsustainable harvesting practices have led to the decimation of Aguaje palm across large areas. Palm fruit extraction traditionally involved gathering fallen fruits. Nowadays, large-scale commercial harvesting often results in cutting down entire palms to access the fruit more quickly. This reduces food availability for uacaris. Studies near Iquitos have shown that intense extraction of Mauritia flexuosa correlates with the decline of seed predators like Uacaris (Bodmer et al., 1999; Meyer & Penn, 2003). The loss of these palms is doubly harmful, impacting both their diet and the integrity of the flooded forest ecosystems they inhabit.

Timber deforestation

The expansion of commercial timber logging concessions poses a hidden but deadly threat to Uacaris. Logging concessions in Peru now cover roughly one-third of the known range of Cacajao calvus ucayalii (Bowler, 2007). Even low-intensity logging operations open up forests, creating access routes that facilitate poaching and settlement.

Wherever humans infiltrate deeply into the rainforest, hunting occurs. In areas where logging has begun, researchers have recorded higher per capita consumption of bushmeat compared to rural villages without logging activity (Bodmer et al., 2006). Logging also disturbs forest composition, removing key tree species that form part of the Uacari’s specialised diet. Consequently, even small-scale logging can degrade habitats beyond repair, pushing already fragile populations closer to extinction.

Infrastructure development

Infrastructure development — including new roads, bridges, and settlements — fragments the continuous forests that Bald-headed Uacaris rely on. These irreplaceable primates are riverine specialists with limited dispersal capabilities, meaning that fragmented landscapes restrict their ability to travel, find mates, and access food. Isolation of small groups leads to reduced genetic diversity, increased inbreeding, and higher vulnerability to disease and environmental changes.

Fragmented habitats are more susceptible to edge effects, such as increased exposure to predators and invasive species. Without large, connected tracts of forest, Uacari communities collapse. Over time, fragmented and degraded forests become population sinks where local extinctions are inevitable unless proactive conservation measures are taken.

Reproduction and Mating

As the rivers swell and the great lakes spread into the trees, new life stirs. The Bald-headed Uacari times births to the bounty of the flood, a fragile promise carried on the rising waters. After a gestation of about six months, a single infant clings to its mother’s shaggy fur, learning the language of the trees — how to leap, how to forage, how to listen to the forest’s unseen warnings.

These young ones grow slowly, nurtured by mothers and guarded by their groups. In the wild, where predators and human threats loom, survival is uncertain. In captivity, away from the murmur of rivers and the hush of rain, they can live up to 30 years — but no cage can offer them what the flooded forest does.

Geographic Range

The Bald-headed Uacari is found in:

- Brazil: Amazonas and Acre

- Peru: Loreto and Ucayali

They move with the rivers through the flooded forest — a living map that changes with the rains. But roads, ranches, and chainsaws carve through this liquid world, isolating the Uacari in shrinking islands of trees. Each patch of forest lost is a story silenced, a life severed from the ancient currents that once connected the Amazon’s heart.

Take Action!

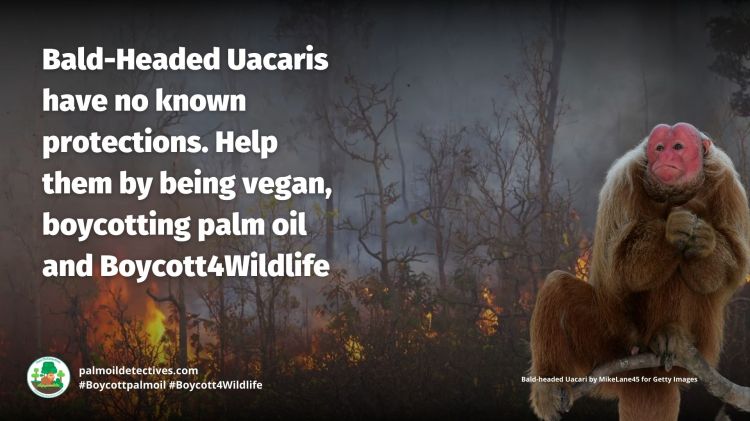

To protect the Bald-headed Uacari, it is essential to support indigenous-led conservation efforts, preserve Amazonian floodplain ecosystems, and stop the drivers of deforestation, including palm oil. Choose products that are 100% palm oil-free and advocate against illegal logging and the illegal wildlife trade. #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife #Vegan

FAQs

What is the current population of Bald-headed Uacaris?

Precise numbers are unknown due to the remoteness of their habitat and limited field studies. However, densities vary from 10 to 17 individuals per square kilometre in some protected areas, with an ongoing population decline estimated at 30% over three generations (2018–2048) (Paim, 2005; Bowler, 2007).

How long do Bald-headed Uacaris live?

In captivity, they can live up to 30 years. However, in the wild, survival is typically shorter due to threats like hunting and habitat loss (Ayres, 1986).

Why do Bald-headed Uacaris have red faces?

Their red faces result from a thinner skin with a dense network of large capillaries. This bright colour may be an honest signal of health, as sick or parasitised individuals show paler faces (Mayor et al., 2015).

Are Bald-headed Uacaris impacted by palm oil plantations?

Yes. Expansion of palm oil and other agricultural activities in the Amazon accelerates forest loss, contributing to their habitat degradation (Global Forest Watch, 2024).

Do Bald-headed Uacaris make good pets?

Absolutely not. Bald-headed Uacaris are highly social, intelligent primates who live in complex social communities. They thrive in their natural environment not in captivity. Keeping them as pets drives illegal hunting, disrupts wild populations, and is extremely cruel. Advocating against the exotic pet trade is crucial to their survival.

Support the conservation of this species

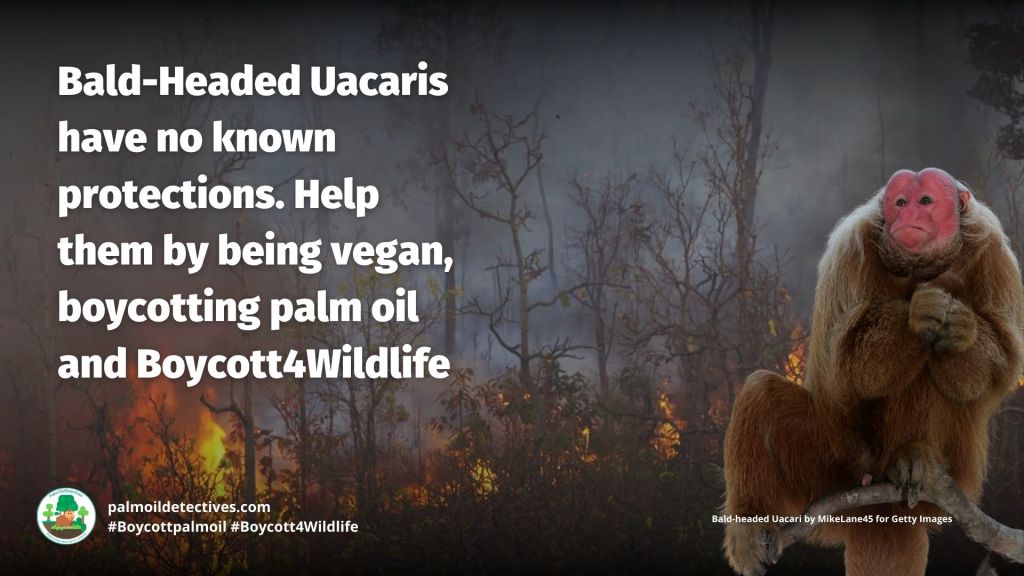

This subspecies is protected within the Mamirauá Sustainable Development Reserve (Ayres et al. 1999). Although no active conservation efforts are in place.

Support the conservation of this species

This animal has no protections in place. Read about other forgotten species here. Create art to support this forgotten animal or raise awareness about them by sharing this post and using the #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife hashtags on social media. Also you can boycott palm oil in the supermarket.

Further Information

Bowler, M., Bodmer, R.E. Diet and Food Choice in Peruvian Red Uakaris (Cacajao calvus ucayalii): Selective or Opportunistic Seed Predation?. Int J Primatol 32, 1109–1122 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-011-9527-6

Mayor, P., Mamani, J., Montes, D., González-Crespo, C., Sebastián, M. A., & Bowler, M. (2015). Proximate causes of the red face of the bald uakari monkey Cacajao calvus. Royal Society Open Science, 2, 150145. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.150145

Veiga, L.M., Bowler, M., Silva Jr, J., Queiroz, H., Boubli, J. & Rylands, A.B. 2020. Cacajao calvus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T3416A17975917. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T3416A17975917.en. Downloaded on 23 February 2021.

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Discover more from Palm Oil Detectives

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Definitely going to follow your blog!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks a lot…I’ve followed back 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person