Black-faced Lion Tamarin Leontopithecus caissara

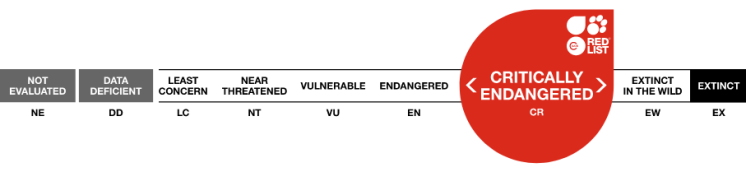

IUCN Status: Critically Endangered

Location: Brazil (Paraná, São Paulo)

Found only in a narrow strip of lowland Atlantic coastal forest in south-eastern Brazil, specifically on Superagüi Island and adjacent mainland areas in Paraná and southern São Paulo.

The black-faced lion #tamarin Leontopithecus caissara, also known as the Superagüi lion tamarin, is listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List. With a total population of fewer than 400 individuals and a fragmented, low-lying coastal habitat of #Brazil, this species is on the edge of extinction. Threats include logging, the illegal #pettrade, palm oil, #soy and #meat deforestation and urban expansion. Conservation efforts have begun, but there is still enormous work to do to protect these irreplaceable #primates. Protect this rare and charismatic #primate by taking urgent action. #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife #Vegan

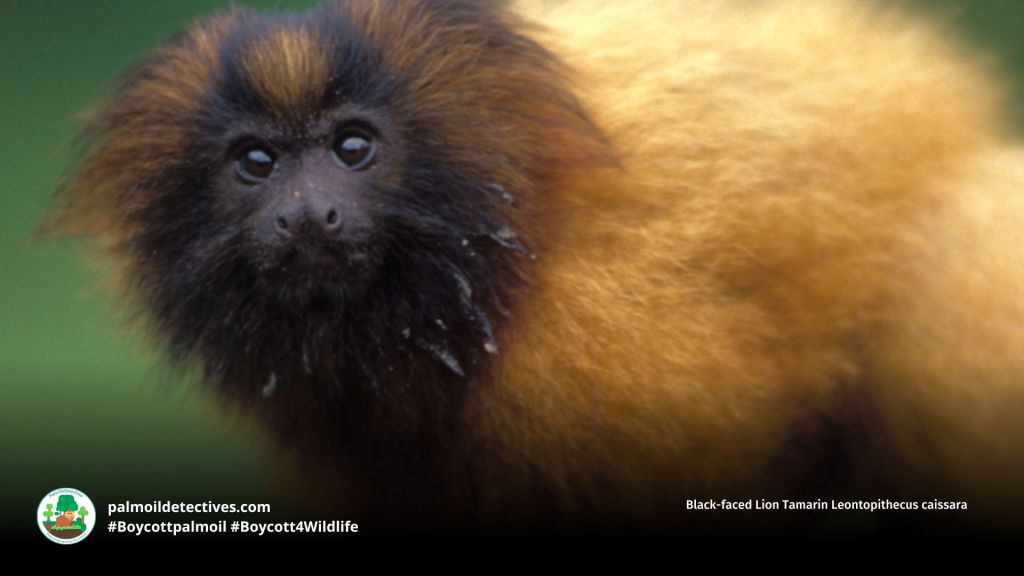

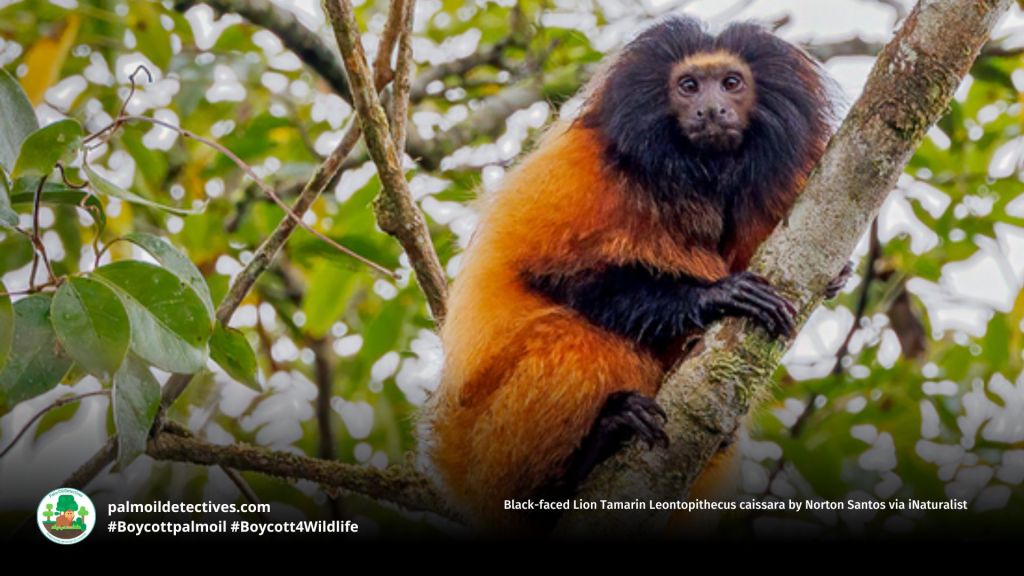

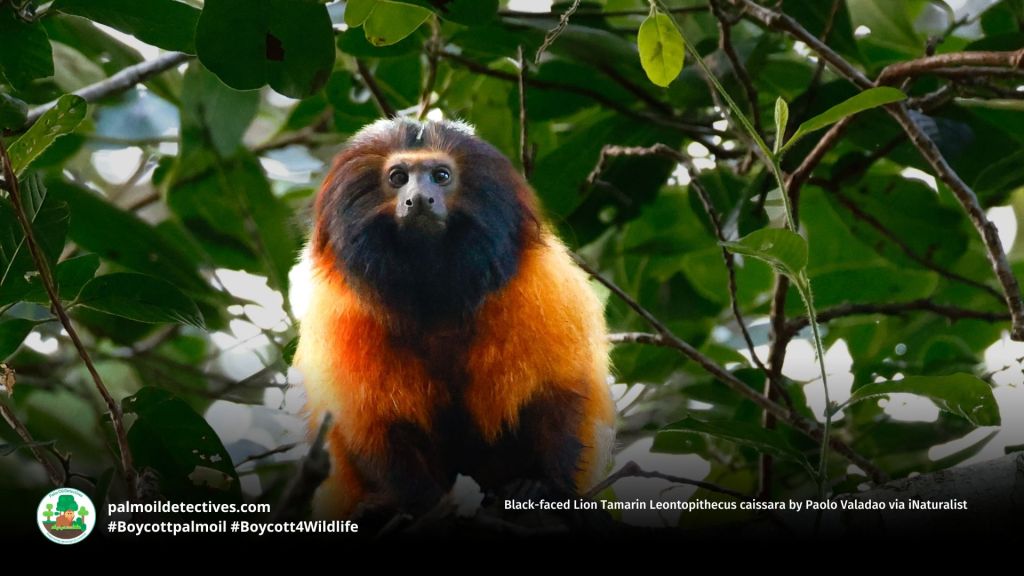

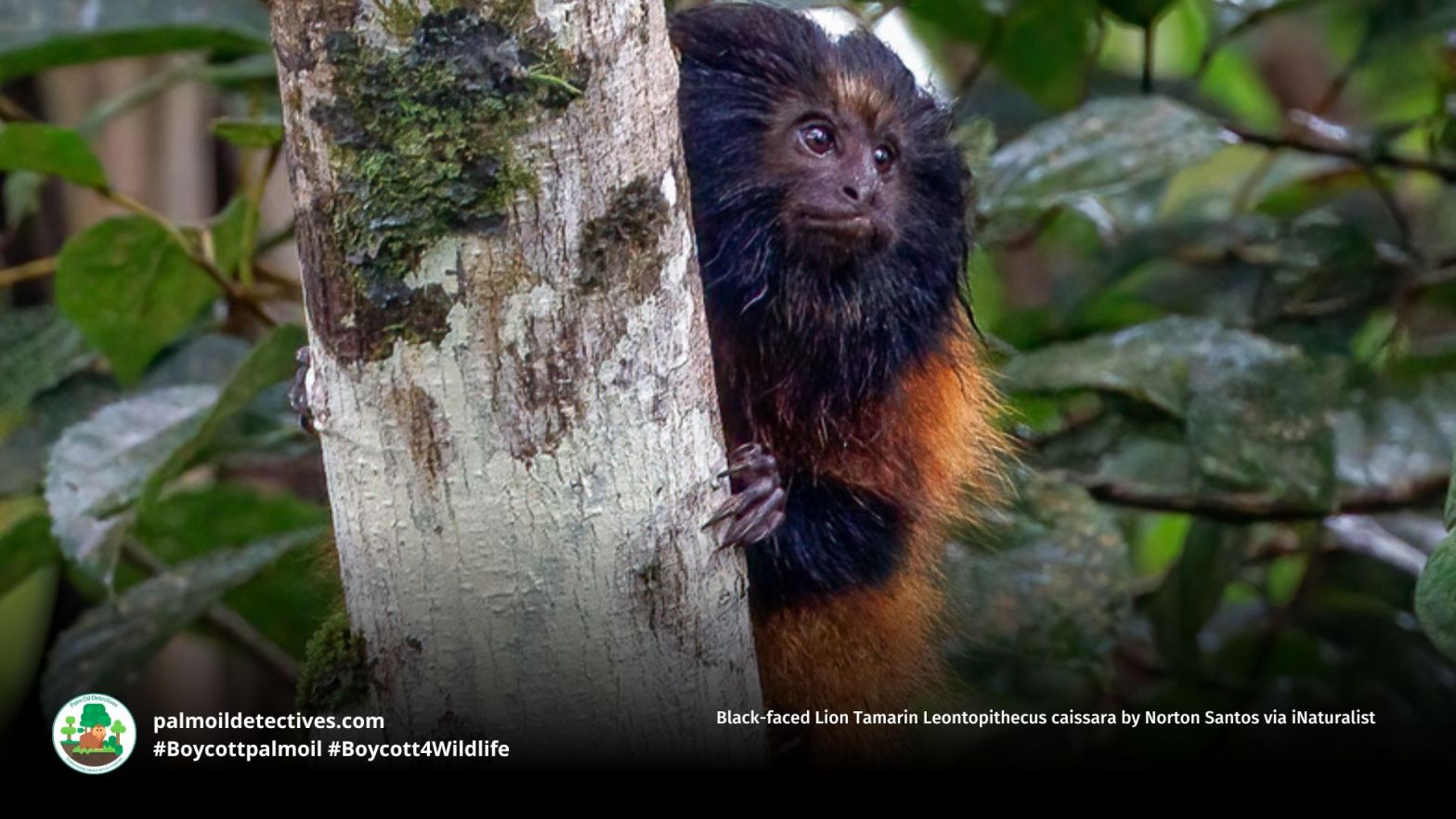

With brilliant bright golden fur 🐵🐒🌞 contrasting to black faces and expressive eyes, Black-Faced Lion #Tamarins are forgotten #monkeys of #Brazil’s Atlantic #Forest. Help them survive #Vegan #BoycottMeat 🥩⛔️🙊 #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2021/03/14/black-faced-lion-tamarin-leontopithecus-caissara/

Black-faced Lion #Tamarins 🐵🐒🤎 are critically #endangered #primates on a narrow strip of Brazil’s Atlantic coast 🇧🇷🌳🚜🔥 #ClimateChange, low population and the illegal #pet trade are threats. Fight for them when you #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2021/03/14/black-faced-lion-tamarin-leontopithecus-caissara/

Appearance and Behaviour

A striking little primate, the black-faced lion tamarin is covered in brilliant golden-orange fur, contrasted by a deep black face, hands, feet, and tail. Their expressive features, long limbs, and silky manes make them one of the most eye-catching members of the lion tamarin family. They move with agility through the canopy and are almost entirely arboreal, spending their days foraging, grooming, and playing in close-knit family groups of 2–8 individuals. Social bonding is strong, with grooming between breeding pairs being particularly important.

Diet

The black-faced lion tamarin has a varied diet consisting mainly of fruits and invertebrates such as insects, spiders, and snails. They also feed on nectar, fungi, and the tender leaves of bromeliads. During the dry season, when other food sources are scarce, they rely more heavily on mushrooms—a rare trait among primates.

Reproduction and Mating

Breeding usually occurs between September and March, with a single dominant female giving birth to twins each year. Their social structure is cooperative, with all group members helping to care for the young. Life expectancy in the wild is unknown but is estimated to be around 15 years, similar to other lion tamarins. A lack of genetic diversity due to population fragmentation increases the risk of inbreeding depression, threatening the species’ long-term survival.

Geographic Range

This species is found only in coastal Brazil, specifically in the Superagüi National Park on Superagüi Island and adjacent mainland in Paraná, and the Jacupiranga State Park in southern São Paulo. They inhabit lowland forest types including arboreal restinga and swampy secondary forests below 40 metres in elevation. A historical canal construction physically separated the island population from mainland groups, severely limiting gene flow.

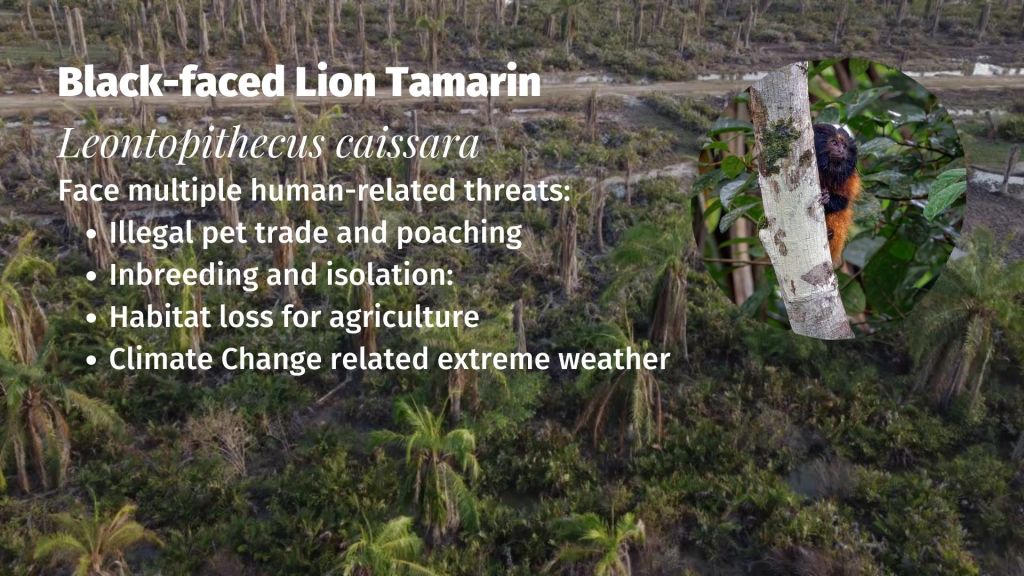

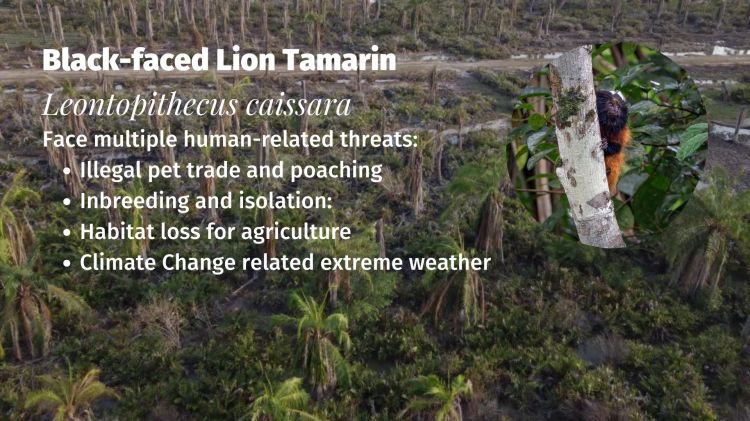

Threats

The Black-faced Lion Tamarin is Critically Endangered and lives in several fragmented small populations that are still subject to loss of suitable habitat. Despite being present in a half-dozen protected areas the estimated number of mature individuals is less than 250, the average number of mature individuals is less than 50, and populations are projected to continue declining due to ongoing loss of suitable habitat in the states of Sao Paulo and Parana.

IUCN RED LIST

Habitat loss and fragmentation:

The Atlantic Forest is one of the most devastated biomes on Earth, and the black-faced lion tamarin’s range has been reduced to a few fragmented patches. Urban sprawl, agriculture, infrastructure development, and unplanned ecotourism have carved up their habitat. Heart-of-palm extraction is a particular threat, removing vital palm trees from which they feed and find shelter.

Illegal pet trade and poaching:

Despite their rarity, black-faced lion tamarins are targeted for the illegal pet trade due to their striking appearance and small size. Many are captured from the wild, leading to the collapse of already fragile family groups. Hunting and poaching for bushmeat, though less common, still occurs in some areas.

Inbreeding and isolation:

The separation of island and mainland populations has led to a severe lack of genetic exchange for Black-faced Lion Tamarins. With just a few isolated groups, the species is experiencing inbreeding depression, weakening its ability to adapt to diseases and environmental changes.

Climate change and extreme weather:

Extreme storms, intensified by climate change, have already destroyed large tracts of tamarin habitat. A 2018 hurricane flattened over 2,000 hectares of forest used by several groups. As a tree-dwelling species with no captive safety population, they are dangerously exposed.

Take Action!

Support indigenous-led conservation projects in the Atlantic Forest. Advocate for the protection and reconnection of forest patches through ecological corridors. Reject the out-of-control palm oil industry that contributes to habitat destruction and fragmentation across Brazil. Never buy or keep exotic primates as pets—it’s a death sentence for wild populations. Choose products that are 100% palm oil-free and commit to a #Vegan lifestyle to protect forests and the beings who call them home. Make sure that you #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife go #Vegan #BoycottMeat

FAQs

How many black-faced lion tamarins are left in the wild?

A decades old population study in 2011 found that population estimates were under 400 individuals across both mainland and island groups (Nascimento et al., 2011). Ongoing research using camera traps and tracking collars is helping to refine this estimate and urgent action is needed to protect these irreplaceable primates.

How long do black-faced lion tamarins live?

Though specific data is limited, these tamarins are believed to live up to 15 years in the wild, similar to their close relatives in the Leontopithecus genus (Amaral Nascimento et al., 2011).

Why is habitat fragmentation so dangerous for them?

Fragmented forests isolate tamarin populations, preventing genetic exchange and leading to inbreeding. Without large, connected areas of forest, young tamarins cannot disperse safely, often being forced to the ground where they are vulnerable to predation or being struck by vehicles (Mongabay, 2022).

What role does palm oil play in the decline of the Black-Faced Lion Tamarin?

Palm oil plantations continue to replace vital forest ecosystems in Brazil. These are often grown illegally, destroying the native trees these tamarins (and many other species) depend on. There is no such thing as ‘sustainable’ palm oil—these green labels are a dangerous form of greenwashing.

Can I keep a black-faced lion tamarin as a pet?

Absolutely not. Keeping tamarins as pets drives illegal trade, tears apart families in the wild, and pushes this Critically Endangered species closer to extinction. If you truly care about them, you must fight against the exotic pet trade and protect their wild homes.

Support the conservation of this species

Merazonia wildlife rescue and sanctuary rehabilitate tamarins and marmosets some of the most trafficked animals in the world.

Further Information

Jerusalinsky, L., Mittermeier, R.A., Martins, M., Nascimento, A.T., Ludwig, G. & Miranda, J. 2020. Leontopithecus caissara. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T11503A17934846. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T11503A17934846.en. Downloaded on 15 February 2021.

Amaral Nascimento, A. T., Schmidlin, L. A. J., Prado, F., Valladares-Padua, C. B., & De Marco Júnior, P. (2011). Population density of black-faced lion tamarin (Leontopithecus caissara). Neotropical Primates, 18(1), 17–21. https://doi.org/10.1896/044.018.0103

Bragança, D and Menegassi, D. (2022). How Brazil is working to save the rare lion tamarins of the Atlantic Forest. Mongabay. Retrieved from https://news.mongabay.com/2022/06/how-brazil-is-working-to-save-the-rare-lion-tamarins-of-the-atlantic-forest/

Nascimento, A. T. A., & Schmidlin, L. A. J. (2011). Habitat selection by, and carrying capacity for, the Critically Endangered black-faced lion tamarin Leontopithecus caissara (Primates: Callitrichidae). Oryx, 45(2), 288–295. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605310000943

Nascimento, A. T. A., Schmidlin, L. A. J., Valladares-Padua, C. B., Matushima, E. R., & Verdade, L. M. (2011). A comparison of the home range sizes of mainland and island populations of black-faced lion tamarins (Leontopithecus caissara) using different spatial analysis. American Journal of Primatology, 73(11), 1114–1126. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20977

Padua, C., & Prado, F. (1996). Notes on the natural history of the black-faced lion tamarin Leontopithecus caissara. Dodo, 32. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270819754_Notes_on_the_natural_history_of_the_black-faced_lion_tamarin_Leontopithecus_caissara

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d). Superagüi lion tamarin. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Superag%C3%BCi_lion_tamarin

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Discover more from Palm Oil Detectives

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Black-faced Lion Tamarin Leontopithecus caissara”