According to a May 2023 report by Transparency International, the top 50 palm oil companies in Indonesia are beset by deep problems: a lack of transparency in company ownership and who are the ultimate beneficiaries of profits, conflicts of interest, revolving-door politics, and politically exposed persons within companies.

All of the above makes the palm oil industry in Indonesia seriously susceptible to corporate capture and corruption. Don’t trust palm oil. Instead #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife every time you shop

A May 2023 report from @anticorruption shows the top 50 #palmoil companies in #Indonesia are deeply susceptible to corporate capture and #corruption. Don’t accept it. Fight back with your wallet #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife

Tweet

May 2023 report by @anticorruption finds #Indonesian #palmoil industry is susceptible to #corruption and murky corporate, government, #financial links. Don’t trust palm oil, instead #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife

Tweet

A report into corporate capture and corruption in Indonesia’s top 50 palm oil companies originally published in Baha Indonesia by Transparency International Indonesia. This report is summarised and analysed by Mongabay journalist Hans Nicholas Jong and republished by Eco-Business on May 5, 2023. Republished below. The Transparency International report’s conclusion is also translated and published below.

“Revolving door practices and cooling-off periods are still not widely recognised in Indonesia. In fact, the trend of businesspeople sponsoring political parties and then being appointed to public office – revolving door practices – is still a well-established practice.

“Even RSPO/ISPO certification cannot guarantee that a certified company is free from illegal and unsustainable practices”

Published by anticorruption NGO Transparency International Indonesia (TII), the report evaluates the top 50 palm oil companies in Indonesia, the world’s biggest producer of palm oil. It focuses in particular on their disclosure practices with respect to their anticorruption programs, lobbying activities, company holdings, and key financial information.

This means there’s a general lack of transparency in palm oil companies’ political activities and how they can interfere with government policies, according to TII program officer Bellicia Angelica. In short, any government lobbying they carry out is done without much scrutiny and monitoring, leading to policies and regulations that are favourable to them, she said.

“This should serve as a warning for the government, the private sector and civil society to regulate the management of the palm oil industry more seriously,” Bellicia said.

The companies on six criteria on a scale of 0-10, with 0 being extremely not transparent and 10 being very transparent. The report found that, on average, the 50 companies only scored 3.5 out of 10.

Certification: Not a guarantee that a palm oil company is free from illegal practices

The report also looked at how many of the palm oil companies were certified, either under Indonesia’s mandatory palm oil certification scheme, the ISPO, or under the voluntary Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO).

It found that only seven of the 50 companies have RSPO and/or ISPO certification that covers not only the parent companies, but also all their subsidiaries.Yet even RSPO/ISPO certification cannot guarantee that a certified company is free from illegal and unsustainable practices, the report said.

An assessment by Greenpeace of 100 RSPO members found that each had more than 100 hectares (250 acres) of illegal plantations inside forest areas in Indonesia, with eight of them having more than 10,000 hectares (24,700 acres).

Greenpeace also identified 252,000 hectares (623,000 acres) of ISPO-certified oil palm plantations inside forest areas, which aren’t permitted under Indonesian zoning laws.

Billionaire oligarchs control dozens of palm oil companies through opaque company structures – with great secrecy

The highest-scoring company in the report, at 7.2, is PT Sinar Mas Agro Resources and Technology (SMART), one of the palm oil arms of Indonesia’s billionaire Widjaja family, presiding over dozens of plantations and oil-processing mills across Indonesia.

Yet even SMART’s score doesn’t necessarily reflect strong anti-corruption measures, Bellicia said: Of the 50 companies, SMART has the highest number of politically exposed persons working for it, she noted.

Akhmad Kamaluddin, a plantation researcher at environmental NGO Auriga, noted that a former vice president of SMART was caught bribing a pair of provincial legislators from Central Kalimantan in 2018. The bribes were meant to head off an investigation into the alleged pollution of a lake by palm oil processing waste and pesticides.

“So it’s very ironic,” Akhmad said. “From this one case, we can see the face of the palm oil industry in Indonesia.”

Agus Purnomo, a director at SMART, said the problem of corporate corruption plagues all industries across in Indonesia, with local officials often seeing companies operating in their jurisdictions as prime targets for extortion.

“If we become an honest actor” — that is, refuse to pay bribes — “we will become an enemy of all stakeholders, from public officials to local communities,” he told Mongabay. “If there’s a rich person, it’s obligatory to pay for various things like sports and religious events, and that’s deemed normal.”

Agus said it’s this culture of permissiveness that needs to be changed, because it nurtures corruption. He added that the government, community leaders and organisation leaders should lead the change.

Before that change comes, however, companies will continue to feel like they have no option other than to comply with demands for money from stakeholders.

“People always assume that companies are evil [because] they bribe [officials] to get permits. While such cases may exist, most [companies] are afraid to say no [to extortion] because the risks are high,” Agus said. “Will you dare to say no if it’s locals who demand [money]? No, because if you do, then the road [to your company] will be blocked. If that’s the case, will you dare to clear the blockade?”

Corporate capture

We found that there are still many companies that are not transparent in informing the policies and processes of interaction between companies and public officials or politicians. This is quite worrying because political connections can lead to conflicts of interest and the impact can give excessive privileges to entrepreneurs who do business in palm oil in the form of policies, subsidies and incentives that can lead to policy capture

50% of companies do not have anticorruption commitments

In compiling their report, researchers from TII first looked at the 50 companies’ anticorruption policies.

They found that 24 of the companies, nearly half, don’t have an anticorruption commitment that applies to all staff members, including high-level board members.

The second aspect they analysed was whether the companies offered anticorruption training to staff. On this measure, they fared even worse: 46 of the companies don’t provide anticorruption training to all of their employees, including executives and directors.

Twenty-six companies don’t have whistleblower systems in place for employees to flag illegal or fraudulent activities anonymously without fear of retaliation. And even when a whistleblower channel was present, it didn’t necessarily protect whistleblowers from retaliation.

The report cited the case of PT Inti Indosawit Subur, a subsidiary of the Asian Agri group, controlled by the billionaire Tanoto family. In 2006, Asian Agri’s then-comptroller, Vincentius Amin Sutanto, was reported by the company to the police for allegedly embezzling US$3.1 million. Vincentius then revealed to the media and the country’s anticorruption agency, the KPK, that Asian Agri, had committed tax evasion from 2002 to 2005.

Despite Inti Indosawit Subur having a whistleblower system in place that should have followed up on Vincentius’s allegation, Asian Agri pressed ahead with its criminal charges against him. Vincentius was eventually convicted in court and sentenced to 11 years in prison in 2008. And in 2013, Asian Agri threatened Vincentius with a defamation lawsuit.

Asian Agri itself was in 2012 convicted of tax evasion and ordered by a court to pay US$205 million in fines.

Wilmar: Irresponsible political lobbying practices

The TII report also assessed the extent of the 50 palm oil companies’ lobbying practices. It found 41 of them lacked responsible lobbying policies or procedures. In particular, these companies don’t forbid donating to political figures.

The report also found that 49 firms, nearly all of them, don’t publish the details of their political donations.

Irresponsible lobbying practices increase the risk of corruption as there’s no transparency in the relationship between companies and policymakers, according to TII. This could result in corrupt practices like bribing policymakers in exchange for favourable policies for the companies.

The report cited the case of PT Wilmar Nabati Indonesia, a subsidiary of Singapore-listed agribusiness giant Wilmar International. Master Parulian Tumanggor a member of its board, claimed he often attended government meetings that determined the allocation of money from the state palm oil fund.

The state fund, which is collected from export tariffs levied on palm oil producers for every shipment of crude palm oil that they sell abroad, is meant to be reinvested in the industry for farmer training, research and development, replanting ageing trees with newer and more productive ones, building infrastructure, and promoting palm oil.

But most of the money collected has instead gone toward palm oil-derived biodiesel, both to subsidise producers and to artificially lower the price of biodiesel at the pump, to make it more competitive with conventional diesel. Between 2015 and 2021, the fund collected 139.17 trillion rupiah (US$9.64 billion) in revenue, and handed 80 per cent of it to biodiesel producers — and less than 5 per cent to small farmers for a replanting program.

Wilmar is the biggest recipient of Indonesian government subsidies to biodiesel producers. In 2017, it received 55 per cent of the total US$530 million distributed by the government to five palm oil companies, or triple the amount it had paid into the fund.

“What PT Wilmar Nabati Indonesia did can be perceived as irresponsible lobbying practices,” TII said in its report.

TII’s Bellicia said there should be an investigation into the company’s role and influence in the fund’s meetings.

“This is what we have to investigate,” she said. “With Master attending those meetings, did it result in more beneficial policies to big companies, resulting in the government siding with corporations instead of people in need?”

However, Indonesia doesn’t have rules banning irresponsible lobbying practices or requiring companies to be transparent about their lobbying activities, Bellicia said.

“In our opinion, lobbying has to be regulated because it’s a doorway to corruption,” she said.

In January, Master was convicted and sentenced to one and a half years in prison for conspiring with a trade ministry official to ensure that four palm oil companies, including Wilmar, could skirt their obligations to allocate a quota for the domestic market.

“This is a concrete example of how corruption will be a never-ending problem [in Indonesia] if things like lobbying are not regulated,” Bellicia said.

A ‘Revolving Door’ between the palm oil industry and the Indonesian government

Another aspect assessed in the TII report is the revolving-door phenomenon that sees officials in charge of regulating the industry going on to take jobs in it, and vice versa.

Government agencies typically hire industry professionals to take advantage of their private sector experience and influence within corporations. Their presence can also help governments gain political support such as donations and endorsements from private firms.

“These individuals [hired by the government] also tend to have biased view in formulating policies and they tend to be in favour of policies that benefit companies but harm people,” the TII report said.

In the other direction, companies also gain an advantage when they hire the very officials previously responsible for overseeing their industry. This allows them to seek favourable legislation and government contracts in exchange for high-paying employment offers, and also to gain inside information on policy discussions.

Unlike some other countries that have issued laws regulating the revolving-door issue, Indonesia has no such restrictions. And in the palm oil industry, the practice is very common: according to the TII report, only two out of the 50 companies assessed are aware of this practice, and none has regulations addressing it.

One example of a regulation used elsewhere to prevent conflicts of interest is the “cooling-off period,” in which former public officials are prohibited from accepting employment in the private sector for a given time period after leaving office.

The report also looked at the presence of politically exposed persons within the 50 companies.

Known as PEPs, these are individuals who hold a prominent public position or function, such as a political party official, industry regulator, law enforcer, or a family member of such a person. PEPs are widely seen as being more prone to bribery, corruption or other potential financial irregularities.

The TII report identified 80 PEPs in 33 companies, including six each at SMART and PT Multi Agro Gemilang. Agus from SMART is one of these. He served as a special assistant to former president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono from 2010 to 2014, just before joining SMART in 2014. He was also a special adviser to the environment minister from 2004 to 2009.

The report characterises Agus as an example of both a politically exposed person and a revolving-door player.

“Am I a politically exposed person? I don’t know. It doesn’t seem like it,” Agus told Mongabay. “But if I didn’t go to the company I currently work in, there are many other companies that want my assistance.”

He added it’s not fair if a politically exposed person is automatically perceived as something of a liability.

“If [the report] gives a score, then it looks like the report is judging [politically exposed persons]. Don’t judge, just prove” that PEPs bring risk to a company, Agus said. “Because people can become a bad actor without them having served in the government before.”

The report noted that the presence of politically exposed persons within a company doesn’t necessarily translate into a bad thing.

“But there really needs to be extra monitoring because politically exposed persons are closely tied to conflicts of interests and trading in influence,” Bellicia said.

Lack of transparency of palm oil company ownership and ultimate beneficiaries

The final aspect assessed in the TII report was data disclosure — whether the companies revealed information on corporate structure, plantation ownership, tax and income, and beneficial owners.

Data transparency can be an effective tool in preventing illicit financial flows and tax evasion, according to the report. But palm oil companies in Indonesia are still largely opaque in this regard, the report said.

For instance, only 34 out of the 50 assessed companies reported who their beneficial owners were to the government, despite this being a mandatory disclosure under a 2018 presidential regulation.

Lack of clarity on corporate ownership makes it difficult for the government and people affected by corporate activities such as deforestation or tax evasion to demand accountability from the company.

The report also found only five companies that disclosed detailed data on their tax payments.

The absence of disclosure of the ultimate beneficial owners of the company as well as the publication of the company’s tax expenses and revenues in detail and separately by country (country country-by-country, indicates loopholes for illicit financial flows by companies.

Transparency International Report 2023 – conclusion.

“This opens up room for tax evasion,” Bellicia said.

The Tanah Merah project in Indonesia’s easternmost region of Papua is an example of how obscure corporate structures and beneficial ownership can increase the risk of corruption, according to the report.

Spanning 280,000 hectares (692,000 acres) in the heart of the largest tract of primary rainforest remaining in Asia, nearly twice the size of Greater London, the project is set to become the world’s largest oil palm plantation.

A 2018 investigation by Mongabay and The Gecko Project revealed that the investors behind the project have employed all the tools of corporate secrecy to hide their identities: shell companies with front addresses, fake and proxy shareholders, and offshore secrecy jurisdictions.

The investigation also revealed that key documents relating to the project were signed by a politician while he was in jail on the island of Java, and that key permits have been hidden from public scrutiny.

Government response

Responding to the TII report, Roro Wide Sulistyowati from the corruption prevention department at the country’s antigraft agency, the KPK, said her office has been pushing for palm oil companies to commit to anticorruption practices.

She added that the KPK has also issued a corruption prevention guideline for companies.

“This year, we want to push [the guideline] to palm oil companies so that they have an anticorruption commitment and antibribery system,” Roro said.

In 2016, the KPK carried out an analysis of the palm oil industry and found a raft of problems, such as tax evasion and the lack of an accountable system to prevent corruption in the issuance of permits.

In 2019 and 2022, the country’s financial audit agency, the BPK, carried out its own assessment of the industry. The 2019 audit found that 81% oil palm plantations in Indonesia are operating in violation of numerous regulations, including excess size, noncompliance with the ISPO standard, failure to allocate sufficient land for smallholder farmers, and lack of relevant operating permits.

The BPK has already finished the 2022 audit, but refused to disclose the findings. Following this latest BPK audit, the government recently announced that it had formed a task force to improve governance in the palm oil industry, including on permits and taxes.

It is not surprising that in recent years, corruption cases involving individuals representing palm oil companies have emerged.

Transparency International Report 2023 – conclusion.

Despite the series of findings from the KPK and the BPK, there’s been little to no improvement in the management of the palm oil industry, Bellicia said.

“If there have been changes [since the 2019 audit], there’s no way the score would be 3.5,” she said. “This score should be a wake-up call for the government.”

‘With little will to fight it, corruption is major risk for Indonesian palm oil’, originally published by Mongabay May 1, 2023. Republished here under the Creative Commons licence.

Below is the conclusion of Transparency International’s report into palm oil industry’s weaknesses and vulnerability to corruption, collusion and corporate capture. Published on May 5, 2023 translated from Baha Indonesia to English. Read original report.

Transparency International Indonesia’s report findings

| Indonesian | English |

|---|---|

| Berdasarkan penilaian yang dilakukan oleh TI Indonesia terhadap 50 perusahaan sawit dengan kinerja baik yang beroperasi di Indonesia, hasil yang dicapai oleh 50 perusahaan sawit tersebut tidak dapat dikatakan baik. Skor rata-rata Transparency in Corporate Reporting dari 50 perusahaan sawit yang dinilai hanya mendapatkan perolehan 3.5/10. Skor rata-rata dari 50 perusahaan sawit dengankinerja baik ini merefleksikan bahwa masih banyak perusahaan sawit tidak transparan dan minim informasi terkait kebijakan perusahaan terkait antikorupsi, inklusivitas, lobi yang bertanggung jawab, praktik keluar-masuk pintu, dan pengungkapan berbagai data yang seharusnya dapat diakses dan diketahui oleh publik. Hal ini juga mengindikasikan bahwa masih banyak perusahaan sawit, baik yang dikelola oleh negara maupun swasta juga cenderung tidak transparan terkait aktivitas perusahaan dan keterlibatannya dalam politik. Urgensi transparansi pelaporan dan aktivitas perusahaan dalam politik menjadi esensial mengingat interaksi antara sektor privat dan sektor publik rawan terhadap ruang gelap yang membuka lebar celah-celah korupsi dan penggelapan pajak yang merugikan negara dan berdampak buruk bagi masyarakat. Dalam penilaian dimensi pertama, yaitu program antikorupsi; hanya 26 perusahaan dari 50 perusahaan sawit yang memiliki komitmen antikorupsi dan 11 perusahaan yang melaporkan kegiatan politik atau mengatur hubungan antara pemerintah dengan perusahaannya. Sedikitnya angka ini menunjukkan bahwa masih ada perusahaan yang tidak mengutamakan kebijakan antikorupsi dan prinsip untuk mengatur hubungan perusahaan dengan pemerintah. Kekosongan kebijakan antikorupsi dan kode etik perilaku atau prinsip dalam pengaturan hubungan perusahaan dan pemerintah dapat menjadi celah korupsi melalui bagaimana perusahaan berinteraksi atau mencoba memberikan pengaruh pada pemerintah mengenai berbagai kebijakan sawit. Hasil penilaian dimensi kedua yang menilai aturan pencegahan korupsi dan inklusivitas perusahaan juga mengisyaratkan bahwa aturan atau pencegahan korupsi masih seakan berlaku hanya bagi pegawai perusahaan di level staf. Idealnya, seluruh lini jabatan perusahaan perlu diatur, diawasi, dan diberikan pemahaman secara ketat terkait pencegahan korupsi. Hanya 4 perusahaan yang secara eksplisit menyatakan aturan tersebut berlaku bagi seluruh level perusahaan, termasuk komisaris dan direksi. Selain itu, pelibatan perempuan di jajaran pengambil keputusan sangat diperlukan mengingat perspektif gender tidak dapat dipisahkan dari pengambilan keputusan bisnis – hanya 18 perusahaan yang menempatkan perempuan dalam jajaran direksinya. Dalam penilaian dimensi ketiga terkait kegiatan lobi yang bertanggung jawab, tidak ada satu pun perusahaan yang memiliki kebijakan terkait hal ini. Absennya aturan perusahaan dalam hal ini menandakan interaksi perusahaan dengan pejabat publik dapat dikatakan tidak transparan. Sama dengan penilaian dimensi ketiga, hasil dimensi keempat terkait praktik keluar masuk pintu juga tidak dapat dijawab dengan baik oleh semua perusahaan; hanya dua perusahaan yang memiliki kesadaran (awareness) terhadap praktik keluar masuk pintu–namun tidak ada regulasi yang mengatur praktik tersebut. Hal ini merefleksikan bahwa perusahaan memandang perpindahan individu dari sektor publik ke sektor privat dan sebaliknya tanpa masa jeda belum mempertimbangkan besarnya risiko konflik kepentingan. Dalam penilaian dimensi kelima terkait keberlanjutan dan standar sertifikasi, sebagian besar perusahaan telah dapat menjawab pertanyaan dengan baik mengingat kewajiban sertifikasi ISPO bagi perusahaan sawit di Indonesia. Sayangnya, masih banyak pula perusahaan yang belum memiliki ISPO bagi anak-anak perusahaannya–padahal sertifikasi ini sangat penting untuk seluruh grup perusahaan, setidaknya menjamin keberlanjutan sawit di Indonesia. Dalam dimensi pengungkapan data, banyak perusahaan sawit yang hanya mempublikasikan rincian data pembayaran pajak dan penerimaan perusahaan secara terkonsolidasi. Selain itu, hanya 7 perusahaan yang mengungkap pemilik manfaat akhir perusahaan yang dilakukan secara eksplisit; sisanya hanya berupa data pemegang saham perusahaan. Tidak adanya pengungkapan pemilik manfaat akhir perusahaan serta publikasi beban pajak dan penerimaan perusahaan secara rinci dan terpisah di negara tempat perusahaan beroperasi (country-by-country), mengindikasikan celah aliran keuangan gelap yang dilakukan oleh perusahaan. Tingkat kepatuhan perusahaan dalam pelaporan pemilik manfaat akhir dapat dikatakan cukup memenuhi prasyarat dengan persentase 68% perusahaan melapor. Namun, masih ada perusahaan yang melaporkan pemilik manfaat akhir berupa nama entitas legal/perusahaan. Selain itu, hadirnya politically exposed persons (PEPs) di 33 perusahaan juga perlu diawasi agar konflik kepentingan dan celah korupsi yang dapat mengintervensi kebijakan sawit yang adil dan berkelanjutan hanya menguntungkan kepentingan pebisnis. | Based on TI Indonesia’s assessment of 50 well-performing palm oil companies operating in Indonesia, the results achieved by these 50 palm oil companies operating in Indonesia are not good. The average score of Transparency in Corporate Reporting of the 50 palm oil companies assessed is only 3.5/10. The average score of the 50 well-performing palm oil companies reflects that the Transparency in Corporate Reporting of the 50 well-performing palm oil companies good performance reflects that there are still many palm oil companies that are not transparent and lack information regarding the company’s anti-corruption policies. information regarding the company’s policies on anti-corruption, inclusiveness, responsible lobbying, out-door practices, and responsible lobbying, door-to-door practices, and disclosure of data that should be publicly accessible and known by the public. This also indicates that there are still many palm oil companies palm oil companies, both state-owned and privately-owned, also tend not to be transparent about their activities and their involvement in politics. The urgency of transparency in reporting and company activities in politics is essential given that the interaction between the private sector and the public sector is prone to dark spaces that open up loopholes for corruption and tax evasion that harm the state and impact the economy. corruption and tax evasion that harm the state and have a negative impact on society. In the assessment of the first dimension, anti-corruption programmes; only 26 out of 50 companies of 50 palm oil companies with anti-corruption commitments and 11 companies that reported on political activities or organising relations between the government and their companies. At least this number shows that there are still companies that do not prioritise their anti-corruption policies and principles to regulate the company’s relationship with the government. The void anti-corruption policies and codes of conduct or principles in regulating company-government relations can be an opening for corruption through how companies and the government can be a loophole for corruption through how companies interact or try to influence the government on various palm oil policies. The results of the second dimension, which assesses the company’s corruption prevention and inclusiveness rules, also suggest that anti-corruption rules or prevention The results of the second dimension assessing the company’s corruption prevention rules and inclusiveness also suggest that the rules or prevention of corruption still seem to apply only to company employees at the staff level. company employees at the staff level. Ideally, all lines of company positions need to be regulated, supervised, and given a strict understanding of corruption prevention. given a strict understanding of corruption prevention. Only 4 companies explicitly state that the rules apply to explicitly state that the rules apply to all levels of the company, including commissioners and directors. In addition, the involvement of women in the decision-making ranks is necessary, given that gender perspectives are inseparable from decision-making. given that gender perspectives are inseparable from business decision-making – only 18 companies that have women on their board of directors. In assessing the third dimension of responsible lobbying, none of the companies had policies in place. company has a policy in this regard. The absence of company rules in this regard indicates that the company’s interactions with public officials can be considered non-transparent. Similar to the assessment of the third dimension, the results of the fourth dimension related to door-to-door practices were also not well answered by the companies. also could not be answered well by all companies; only two companies had a good awareness of door-to-door practices-but there are no regulations governing the practice. However, there is no regulation governing the practice. This reflects the fact that companies perceive the movement of of individuals from the public sector to the private sector and vice versa without a break in service has not yet the risk of conflicts of interest. In the assessment of the fifth dimension related to sustainability and certification standards, most of the companies have been able to answer the questions well given the ISPO certification obligation for palm oil companies in Indonesia. certification for palm oil companies in Indonesia. Unfortunately, there are still many companies that do not yet ISPO for their subsidiaries – even though this certification is very important for the whole group, at least to ensure the sustainability of the company. at least to ensure the sustainability of palm oil in Indonesia. In the dimension of data disclosure, many palm oil companies only publish details of tax payments and company revenues. data on tax payments and company revenues on a consolidated basis. In addition, only 7 companies explicitly disclose the ultimate beneficial owners of the company; the rest only provide data on the company’s shareholders. The absence of disclosure of the ultimate beneficial owners of the company as well as the publication of the company’s tax expenses and revenues in detail and separately by country (country country-by-country, indicates loopholes for illicit financial flows by companies. The level of company compliance in reporting the ultimate beneficial owner can be said to be sufficiently fulfil the prerequisites with 68% of companies reporting. However, there are still companies that report the ultimate beneficial owner in the form of a legal entity/company name. In addition, the presence of the presence of politically exposed persons (PEPs) in 33 companies also needs to be monitored so that conflicts of interest and corruption loopholes that can intervene in the reporting of beneficial owners can be avoided. and corruption loopholes that can intervene in fair and sustainable palm oil policies that only benefit business interests. in favour of business interests. |

| Mewajibkan Komitmen Antikorupsi Perusahaan Sawit merupakan komoditas ekspor andalan Indonesia. Namun pelaku usaha di sektor ini masih sedikit yang tidak mentoleransi adanya praktik korupsi–meskipun sudah mampu melakukan ekspansi bisnis di tingkat global. Bukan suatu hal yang mengejutkan apabila dalam beberapa tahun terakhir bermunculan kasus korupsi yang melibatkan individu-individu yang mewakili perusahaan sawit–seperti kasus korupsi pemberian persetujuan ekspor (PE) Crude palm oil (CPO).68 Sudah sepatutnya pemerintah memprioritaskan agenda pencegahan korupsi di korporasi terhadap perusahaan yang berbisnis di komoditas sawit dan menagih komitmen antikorupsi perusahaan sawit. | Requiring Corporate Anti-Corruption Commitments Palm oil is Indonesia’s main export commodity. But businesses in this sector are still a few that do not tolerate corrupt practices – even though they have been able to expand their business globally. to expand their business on a global level. It is not surprising that in recent years, corruption cases involving individuals representing palm oil companies have emerged, such as the corruption case of Crude palm oil (CPO) export approval (PE).68 palm oil (CPO) export approval (PE).68. It is only fitting that the government prioritises a corruption prevention agenda for companies doing business in corporations and a corruption prevention agenda for companies doing business in the palm oil commodity and demand an anti-corruption commitment from palm oil companies. |

| Mendorong Implementasi, monitoring, dan pengawasan kebijakan dalam kegiatan antikorupsi dan keterlibatan politik perusahaan Tidak hanya pada tataran kebijakan (policy), pemerintah juga harus memastikan bahwa perusahaan telah mengimplementasikan kebijakan antikorupsi (practice). Berdasarkan hasil penilaian kami, sangat sedikit perusahaan yang mengimplementasikan kebijakan antikorupsi dan keterlibatan politik perusahaan–tataran practice–seperti pelatihan, monitoring, dan pengawasan. Keberadaan peraturan antikorupsi namun tidak diikuti dengan implementasinya akan membuat kebijakan antikorupsi hanya sebagai paper tiger dan mendelegitimasi eksistensi kebijakan antikorupsi dan kebijakan keterlibatan politik perusahaan. | Encourage the implementation, monitoring and supervision of policies on anti-corruption activities and political engagement of palm oil companies. Not only at the policy level, the government must also ensure that companies have implemented anti-corruption policies. companies have implemented anti-corruption policies (practice). Based on the results of our our assessment, very few companies have implemented anti-corruption policies and corporate political engagement at the practice level-such as training, monitoring, and supervision. supervision. The existence of an anti-corruption regulation but not its implementation will make the anti-corruption policy only a practice. will make the anti-corruption policy a paper tiger and delegitimise the existence of anti-corruption and political engagement policies. |

| Perkuat transparansi besaran pendapatan (revenue) dan pembayaran pajak (tax payment)dari korporasi sawit ke Pemerintah Munculnya kasus korupsi minyak goreng pada tahun lalu membuat pemerintah bergerak untuk mengaudit seluruh perusahaan sawit di Indonesia serta memerintahkan agar perusahaan sawit berkantor pusat di Indonesia. Secara implisit, upaya pemerintah untuk ‘memaksa’ perusahaan berkantor pusat di Indonesia itu disebabkan karena adanya dugaan praktik Base Erosion Profit Shifting (BEPS), yaitu praktik penggerusan pajak dan pemindahan keuntungan yang dihasilkan dari negara yang menjadi lokasi aktivitas bisnis–Indonesia–ke negara tujuan yang memiliki tarif pajak yang lebih rendah–Singapura.69 Menyadari adanya potensi kehilangan pajak akibat praktik diatas, Pemerintah menerbitkan Peraturan Menteri Keuangan (PMK) No. 213/2016 tentang Jenis Dokumen dan/atau Informasi Tambahan yang Wajib Disimpan oleh Wajib Pajak yang Melakukan Transaksi dengan Para Pihak yang Memiliki Hubungan Istimewa dan Tata Cara Pengelolaannya, dan salah satu dokumen yang wajib dilaporkan adalah laporan per negara (Country-by-Country Report).70 Dalam laporan-per-negara, alokasi penghasilan, pajak yang dibayar, dan aktivitas bisnis di setiap yurisdiksi anak usaha wajib dilaporkan. 71 Laporan tersebut diyakini dapat dijadikan oleh Pemerintah sebagai senjata untuk memerangi praktik penggelapan pajak. Hasil penelusuran kami pun menunjukkan bahwa belum ada perusahaan yang mempublikasikan laporan per negara kepada publik. Selain itu, laporan per negara tidak membuka ruang bagi publik untuk melakukan verifikasi terhadap kebenaran informasi yang disampaikan oleh perusahaan dalam laporan per negara yang disampaikan oleh perusahaan ke Direktorat Jenderal Pajak (DJP). Sebaiknya dokumen ini dijadikan sebagai dokumen yang dapat diakses dan dipublikasikan kepada publik.72 | Strengthen transparency of revenue and tax payments from palm oil corporations to the government The emergence of the cooking oil corruption case last year made the government move to audit all palm oil companies in Indonesia and ordered palm oil companies to be headquartered in Indonesia. Implicitly, the government’s attempt to ‘force’ companies to be headquartered in Indonesia was due to the alleged practice of Base Erosion Profit Shifting (BEPS), which is the practice of profit shifting. Shifting (BEPS), which is the practice of tax erosion and profit shifting generated from the country of business activity-Indonesia. from the country of business activity-Indonesia-to a destination country with a lower tax rate-Singapore. 69 Recognising the potential for tax loss due to the above practice, the Government issued the Minister of Finance Regulation (MoFTR) on the practice. The Government issued Minister of Finance Regulation (PMK) No. 213/2016 on Types of Documents and/or Additional Information that Must be Kept by Taxpayers Conducting Transactions with Related Parties and the Procedures for Their Management, and one of the documents that must be reported is the Country-by-Country Report.70 In the Country-by-Country Report, the allocation of income, taxes paid, and business activities in each subsidiary jurisdiction must be reported. 71 The report is believed to be used by the Government as a weapon to combat tax evasion. Our search results also show that there are no companies that publish country-by-country reports to the public. In addition, the country-by-country report does not allow the public to verify the accuracy of the information submitted by the company in the country-by-country report submitted by the company to the Directorate General of Taxes (DGT). This document should be made accessible and publicised to the public.72 |

| Pengawasan terhadap Politically-Exposed Persons (PEPs) Maraknya keberadaan Politically-Exposed Persons (PEPs) di 50 perusahaan sawit di Indonesia menunjukkan bahwa koneksi politik sangat berharga bagi perusahaan sawit. Sko Corruption Perception Index (CPI) tahun 2022 pun menurun 4 poin–penurunan skor terburuk sejak tahun reformasi. Penurunan skor disebabkan oleh konflik kepentingan antara pebisnis dan pejabat publik dinilai semakin terang enderang.73 Apabila pemerintah berkomitmen kuat untuk memperbaiki skor CPI, sudah seharusnya pemerintah mengimplementasikan aturan konflik kepentingan–dimulai dari kabinet Presiden Jokowi–dan mendorong perusahaan sawit untuk tidak merekrut direksi dan komisaris yang tergolong sebagai Politically-Exposed Persons (PEPs). | Supervision of Politically-Exposed Persons (PEPs) The prevalence of Politically-Exposed Persons (PEPs) in 50 palm oil companies in Indonesia shows that political connections are valuable to palm oil companies. The 2022 Corruption Perception Index (CPI) score dropped by 4 points – the worst drop since reformasi. The decline in the score is due to the conflict of interest between business people and public officials, which is considered to be increasingly obvious.73 If the government is strongly committed to improving the CPI score, it should be the government’s responsibility to improve the CPI score. to improve the CPI score, the government should implement conflict of interest rules-starting with President Jokowi’s cabinet of interest rules – starting from President Jokowi’s cabinet – and encourage palm oil companies to not recruit directors and commissioners who are classified as Politically-Exposed Persons (PEPs). (PEPs). |

| Perusahaan Sawit di Indonesia Memastikan adanya kebijakan antikorupsi yang esensial Selain menagih komitmen antikorupsi perusahaan sawit, pemerintah juga harus memastikan bahwa perusahaan sawit turut menyusun kebijakan antikorupsi yang esensial, seperti aturan terkait suap, gratifikasi, donasi politik, dan konflik kepentingan. Dalam laporan ini ditemukan bahwa masih sedikit perusahaan sawit yang memiliki aturan-aturan esensial yang telah disebutkan sebelumnya. Penyusunan peraturan antikorupsi dinilai penting karena aturan tersebut berguna untuk memberikan pedoman bagi karyawan, direksi, dan komisaris perusahaan dalam berperilaku mewakili nama perusahaan dan agar korporasi tidak dimintai pertanggungjawaban pidana karena tidak melakukan langkah-langkah yang diperlukan untuk melakukan pencegahan korupsi. | Palm Oil Companies in Indonesia Ensure essential anti-corruption policies are in place In addition to demanding anti-corruption commitments from palm oil companies, the government must also ensure that palm oil companies develop essential anti-corruption policies, such as rules on anti-corruption. that palm oil companies also develop essential anti-corruption policies, such as rules on bribery, gratuities, political donations and conflicts of interest. This report found that there are still few palm oil companies that have the essential rules mentioned earlier. mentioned earlier. The development of anti-corruption regulations is important because they provide guidance to employees, employees’ supervisors, and employees. to provide guidelines for employees, directors and commissioners of the company in their in their behaviour on behalf of the company and so that the corporation is not held criminally criminal liability for not taking the necessary steps to prevent corruption.74 |

| Perkuat mekanisme peniup peluit Kebijakan antikorupsi dan keterlibatan politik perusahaan sudah sepatutnya dilengkapi sistem yang bertujuan untuk menerima laporan dan mendeteksi kecurangan, seperti sistem pelaporan pelanggaran (Whistle-Blowing System/WBS). Hanya setengah dari 50 perusahaan sawit yang kami nilai yang memiliki WBS. Untuk meningkatkan efektivitas, perusahaan harus menjamin bahwa WBS yang dimiliki telah menjamin perlindungan kepada pelapor, memperbolehkan pelaporan secara anonim, dan menjaga independensi pengelola WBS. | Strengthen the whistleblower mechanism Companies’ anti-corruption and political engagement policies should be complemented by systems aimed at receiving reports and detecting fraud, such as whistle-blowing systems (WBS). Only half of the 50 palm oil companies we assessed have a WBS. To improve effectiveness, companies should ensure that their WBS provides protection to whistleblowers, allows anonymous reporting, and maintains the independence of the WBS manager |

| Transparansi kegiatan lobbying Praktik lobbying–baik secara langsung maupun tidak langsung–sangat lekat dengan komoditas sawit. Komoditas ini sering dilabeli sebagai komoditas yang memicu tingginya tingkat deforestasi dan merusak biodiversitas kawasan hutan. Komoditas ini juga menjadi salah satu sasaran utama penerapan prinsip NDPE (No Deforestation, No Peat, and No Exploitation). Namun ada saja upaya lobi untuk membajak konsep deforestasi, misalkan saja upaya melabeli sawit sebagai tanaman hutan.75 Sudah seharusnya pemerintah memaksa perusahaan sawit–dan asosiasi bisnis sawit–untuk transparan dalam melakukan praktik lobbying agar tidak ada policy capture dalam kebijakan yang mengatur komoditas ekspor andalan Indonesia ini. | Transparency of lobbying activities The practice of lobbying-both directly and indirectly-is closely associated with palm oil commodities. This commodity is often labelled as the one that triggers high deforestation and destroying the biodiversity of forest areas. This commodity has also become one of the main targets for the implementation of NDPE (No Deforestation, No Peat, and No Exploitation) principles. Exploitation). However, there are lobbying efforts to hijack the concept of deforestation, for example labelling palm oil as a forest crop.75 The government should have forced palm oil companies-and palm oil business associations-to be transparent in their lobbying practices so that there is no policy capture. lobbying practices so that there is no policy capture in the policies governing Indonesia’s flagship export commodity. Indonesia’s flagship export commodity. |

| Mewajibkan pihak ketiga dan penyedia barang dan jasa (PBJ) untuk mematuhi kebijakan antikorupsi perusahaan Untuk memudahkan praktik korupsi, korporasi seringkali memanfaatkan jasa perantara/intermediary untuk menyamarkan praktik tersebut.76 Selain itu, penyedia barang dan jasa (PBJ) yang ditunjuk oleh korporasi juga seringkali terpilih tanpa melalui proses uji tuntas integritas (integrity due diligence). Berdasarkan penilaian kami, sangat sedikit perusahaan sawit yang mewajibkan perantara dan penyedia barang dan jasa (PBJ) untuk mematuhi kebijakan antikorupsi perusahaan dan melalui proses cek latar belakang, pemilik manfaat (beneficial owner), dan Politically-Exposed Persons (PEPs). Sebaiknya korporasi mewajibkan kedua pihak di atas untuk mematuhi kebijakan antikorupsi perusahaan agar kekosongan hukum ini tidak menjadi bumerang ketika perusahaan tersangkut kasus tindak pidana. | Require third parties and providers of goods and services (PBJ) to comply with the company’s anti-corruption policy To facilitate corrupt practices, corporations often utilise the services of intermediaries to disguise the practice. In addition, providers of goods and services appointed by corporations are also often selected without going through an integrity due diligence process. Based on our assessment, very few palm oil companies require intermediaries and PEPs to comply with the company’s anti-corruption policy and go through a background check process, beneficial owners, and Politically-Exposed Persons (PEPs). Corporations should require both of the above parties to comply with the company’s anti-corruption policy so that this legal vacuum does not backfire when the company is involved in a criminal case. |

| Pengaturan praktik revolving door dan cooling-off period Praktik keluar-masuk pintu (revolving door) dan masa jeda (cooling-off period) masih tidak dikenal secara luas di Indonesia. Padahal, tren di mana pebisnis yang dahulu menjadi sponsor bagi partai politik kemudian ditunjuk menjadi pejabat publik–praktik revolving door masih menjadi praktik yang dilaksanakan secara terang benderang.77 Hasil penilaian kami menunjukkan bahwa tidak ada satu pun perusahaan sawit yang telah mengatur praktik revolving door dan cooling-off period. Sudah sepatutnya pemerintah Indonesia yang mengklaim lebih mengutamakan pencegahan korupsi daripada penindakan korupsi–Operasi Tangkap Tangan (OTT)–pasca penerbitan UU KPK tahun 2019 untuk mengatur praktik revolving door dari sektor publik ke sektor swasta maupun sebaliknya. | Regulating revolving door practices and cooling-off periods Revolving door practices and cooling-off periods are still not widely recognised in Indonesia. In fact, the trend of businesspeople sponsoring political parties and then being appointed to public office – revolving door practices – is still a well-established practice. 77 Our assessment shows that not a single palm oil company has regulated revolving door practices and cooling-off periods. It is appropriate for the Indonesian government, which claims to prioritise corruption prevention over corruption prosecution-Operasi Tangkap Tangan (OTT)-after the issuance of the 2019 KPK Law to regulate revolving door practices from the public sector to the private sector and vice versa. |

| Pentingnya mewajibkan korporasi untuk melaporkan pemilik manfaat (BO) dan verifikasi data BO Pemerintah telah mewajibkan korporasi untuk melaporkan pemilik manfaat korporasi–know your beneficial owner–melalui penerbitan Peraturan Presiden Nomor 13 tahun 2018 tentang Penerapan Prinsip mengenali Pemilik Manfaat dari Korporasi dalam rangka Pencegahan dan Pemberantasan Tindak Pidana Pencucian Uang dan Tindak Pidana Pendanaan Terorisme. Namun analisis kami terhadap 50 perusahaan sawit yang beroperasi di Indonesia menunjukkan masih ada perusahaan yang belum melaporkan pemilik manfaat. Kemudian, masih ada korporasi yang melaporkan nama korporasi lainnya sebagai pemilik manfaat. Padahal, pemilik manfaat adalah orang perseorangan (nature person). Sejalan dengan isi dari Peraturan Menteri Hukum dan HAM (PermenkumHAM) Nomor 21 tahun 2019 tentang Tata Cara Pengawasan Penerapan Prinsip Mengenali Pemilik Manfaat dari Korporasi, sudah seharusnya Kementerian Hukum dan HAM (KemenkumHAM) melakukan verifikasi terhadap kebenaran laporan pemilik manfaat yang dilaporkan oleh korporasi dan menjatuhkan sanksi bagi korporasi yang menyampaikan pemilik manfaatnya secara tidak benar | The importance of requiring corporations to report beneficial owners (BO) and verification of BO data The government has made it mandatory for corporations to report corporate beneficial owners – know your beneficial owner – through the issuance of Presidential Regulation No. 13/2018 on the Implementation of the Principle of Recognising Beneficial Owners of Corporations in the context of Preventing and Eradicating the Criminal Acts of Money Laundering and the Criminal Acts of Financing Terrorism. However, our analysis of 50 palm oil companies operating in Indonesia shows that there are still companies that have not reported their beneficial owners. Then, there are still corporations that report the names of other corporations as beneficial owners. In fact, the beneficial owner is a natural person. In line with the contents of the Minister of Law and Human Rights Regulation (PermenkumHAM) Number 21 of 2019 concerning Procedures for Supervising the Implementation of the Principle of Recognising Beneficial Owners of Corporations, the Ministry of Law and Human Rights (KemenkumHAM) should report the names of other corporations as beneficial owners. Law and Human Rights (KemenkumHAM) should verify the accuracy of the beneficial owner report reported by the corporation and impose sanctions on corporations that submit their beneficial owners incorrectly. |

| Menagih komitmen transparansi keterlibatan politik perusahaan Selain transparansi program antikorupsi perusahaan, salah satu isu lainnya yang perl diwajibkan bagi perusahaan sawit adalah transparansi keterlibatan politik perusahaan (corporate political engagement). Kami menemukan bahwa masih banyak perusahaan yang belum transparan dalam menginformasikan kebijakan dan proses interaksi antara perusahaan dengan pejabat publik atau politisi. Hal ini cukup mengkhawatirkan karena koneksi politik dapat mengarah kepada konflik kepentingan dan dampaknya dapat memberikan privilese yang berlebih kepada pengusaha yang berbisnis di sawit dalam bentuk kebijakan, pemberian subsidi dan insentif yang bisa saja mengarah pada policy capture. Oleh karenanya, di samping mendorong agenda pencegahan korupsi di korporasi, pemerintah juga perlu memprioritaskan transparansi keterlibatan politik perusahaan. | Demanding transparency in corporate political engagement In addition to the transparency of corporate anti-corruption programmes, one of the other issues that needs to be addressed is the transparency of corporate political engagement. We found that there are still many companies that are not transparent in informing the policies and processes of interaction between companies and public officials or politicians. This is quite worrying because political connections can lead to conflicts of interest and the impact can give excessive privileges to entrepreneurs who do business in palm oil in the form of policies, subsidies and incentives that can lead to policy capture. Therefore, in addition to pushing the corruption prevention agenda in corporations, the government also needs to prioritise transparency of corporate political involvement. |

ENDS

Read more about palm oil corruption, collusion and greenwashing

PalmWatch: An Open-Source Tool That Empowers You To Hold Palm Oil Greenwashers To Account

A groundbreaking open-source tool by the University of Chicago called PalmWatch, shines a light on the darkest parts of the palm oil industry.

PalmWatch is a free web-based tool…

Read moreAir pollution from palm oil deforestation is a human rights issue affecting everyone in Asia

Forest-fire haze drifting from Indonesia to neighbouring countries every dry season has eluded efforts to curb it.

Land clearing by burning is prohibited in Indonesia and Malaysia. However,…

Read moreThe UK’s hunger for palm oil, soy and beef putting huge pressure on world’s forests

Urgent call to action! 🌍 #UK’s heavy use of #palmoil #soy & #beef fuels global #deforestation. Demand stricter regulations & transparency. Make every purchase count and #Boycottmeat #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife,…

Read moreBehind The Green Lie of Sustainable Aviation Biofuel (SAF)

“Sustainable” Aviation Fuel (SAF) is a biofuel alternative to using fossil fuels for powering planes and cars. SAF is being aggressively marketed by multiple industries as a greener alternative…

Read moreResearch: Palm oil deforestation makes conditions better for disease-carrying Aedes albopictus mosquitoes

A 2023 study published in Nature has found that cutting down rainforest to grow palm oil makes it easier for certain disease-carrying bugs like Aedes albopictus mosquitoes to thrive.…

Read morePalm oil deforestation in Guatemala: Certifying products as ‘sustainable’ is no panacea: University of Michigan

Newly published research from the University of Michigan reveals that despite the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) certification system being influential, its effectiveness in reducing deforestation is uncertain.…

Read moreAustralia must not be a dumping ground for palm oil made from slavery: The Australian Greens

The recently released Global Slavery Index reveals that Australia risks importing goods amounting to US $17.4 billion, which are suspected to be produced via forced labour.

A ban of…

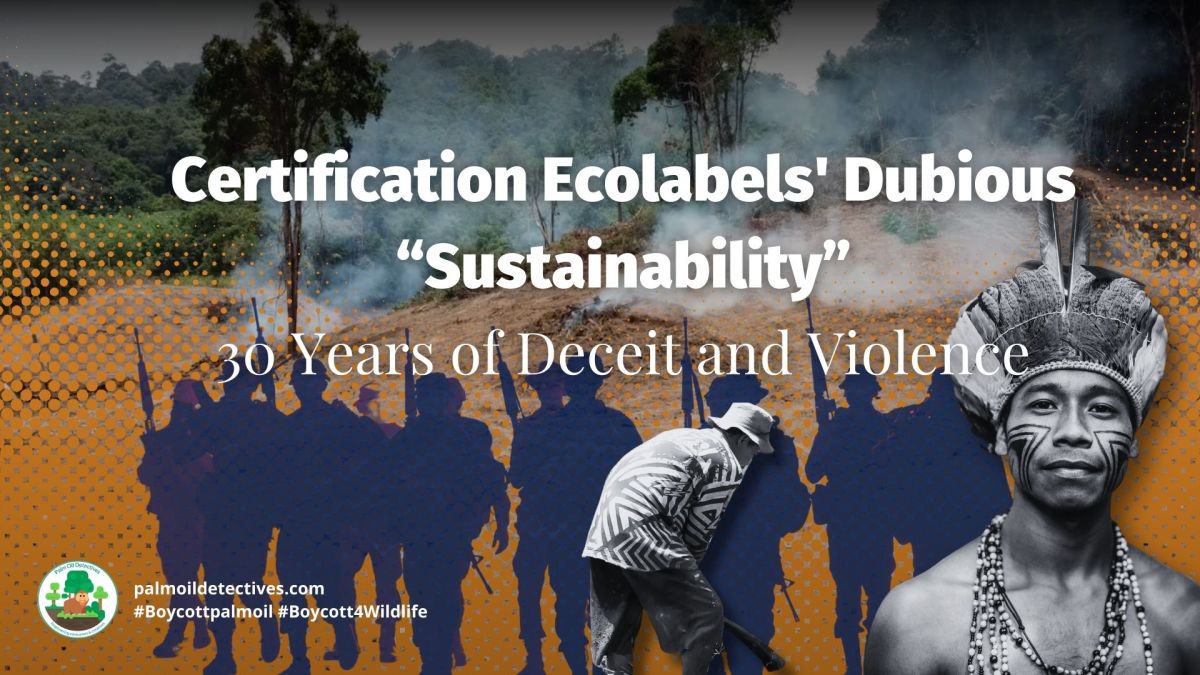

Read moreCertification Ecolabels’ Dubious “Sustainability”: 30 Years of Deceit and Violence

Ecolabels like RSPO and FSC are involved in networks of extensive greenwashing. They exist to conceal corporations’ environmental damage rather than fighting it. With three decades dubious promises from…

Read more‘Just the beginning’: dawn of greenwash era for journalism in Asia?

Curtailed press freedom in Asia makes the job of calling out greenwashing increasingly difficult – at a time when corporate accountability is critical in the fight against climate change.…

Read moreOligarchs weaken Indonesia’s fight against corruption

Indonesia’s efforts to fight government corruption are being corrupted from within parliament and backed by big palm oil, timber and mining businesses. Story via 360Info. Fight back every time…

Read moreRead more about RSPO greenwashing

Big brands using “sustainable” RSPO palm oil yet still causing deforestation (there are many others)

Colgate-Palmolive

Despite global retail giant Colgate-Palmolive forming a coalition with other brands in 2020, virtue-signalling that they will stop all deforestation, they continue to do this – destroying rainforest and releasing mega-tonnes of carbon…

Read moreProcter & Gamble

Despite decades of promises to end deforestation for palm oil Procter & Gamble or (P&G as they are also known) have continued sourcing palm oil that causes ecocide, indigenous landgrabbing, and the habitat…

Read moreKelloggs/Kellanova

In late 2023, Kelloggs became Kellanova for their US arm. Savvy consumers have been pressuring Kelloggs for decades to cease using deforestation palm oil. Yet they actually haven’t stopped this. From their website:…

Read moreJohnson & Johnson

Global mega-brand Johnson & Johnson have issued a position statement on palm oil in 2020. ‘At Johnson & Johnson, we are committed to doing our part to address the unsustainable rate of global…

Read morePZ Cussons

PZ Cussons is a British-owned global retail giant. They own well-known supermarket brands in personal care, cleaning, household goods and toiletries categories, such as Imperial Leather, Morning Fresh, Carex, Radiant laundry powder and…

Read moreContribute in five ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Thanks dear friend once again for the share

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Ned

LikeLike