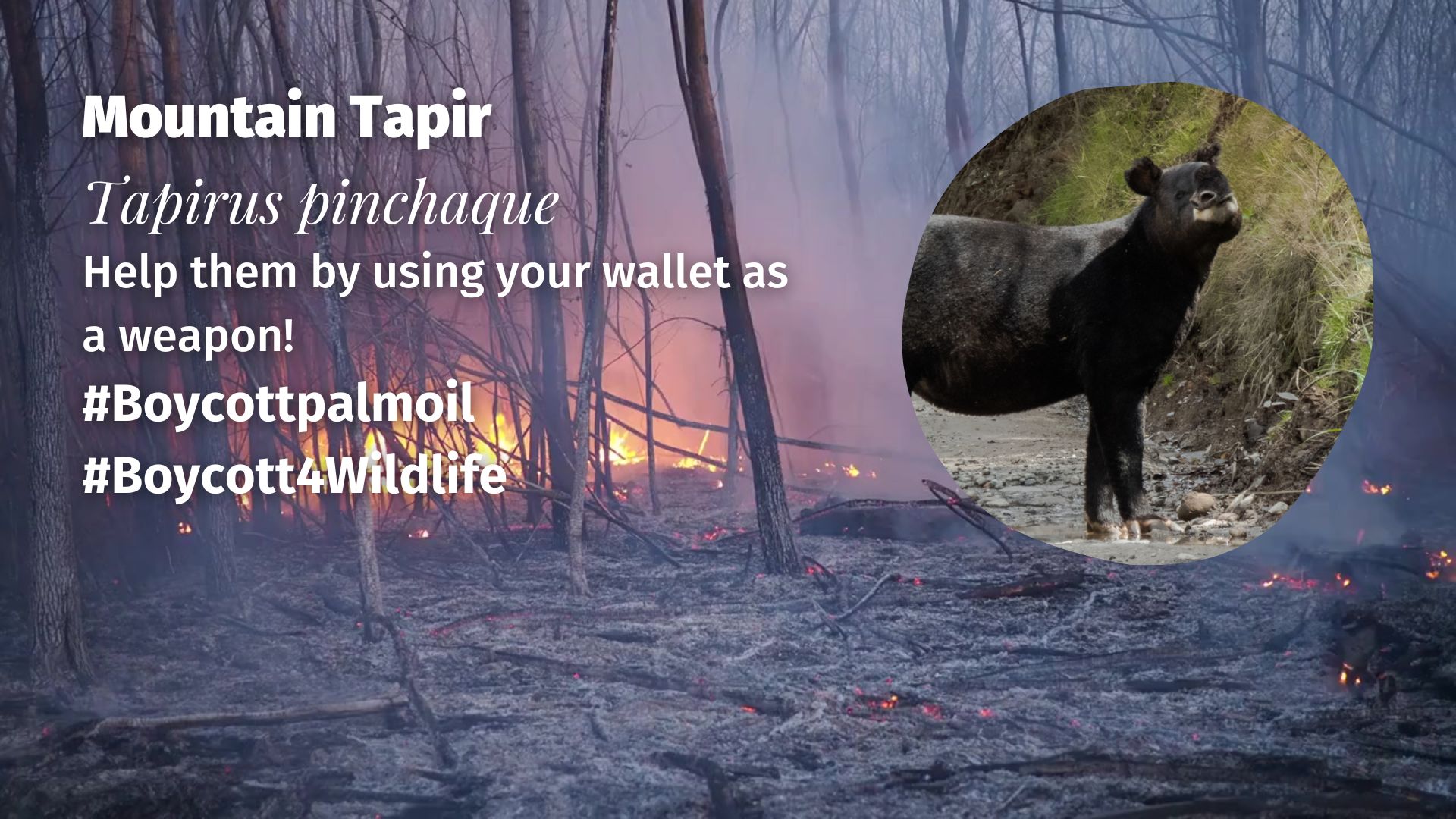

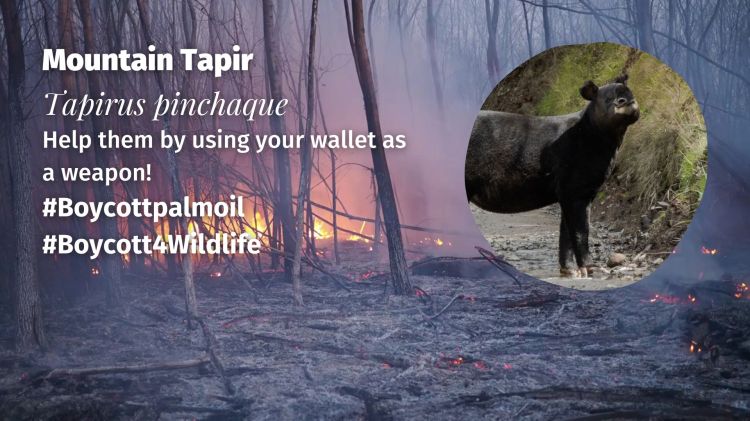

Mountain Tapir Tapirus pinchaque

IUCN Red List Status: Endangered

Location: Colombia, Ecuador, northern Peru

Mountain Tapirs inhabit the high Andean cloud forests and páramos above 2,000 metres in the northern Andes. They are found in Colombia’s Central and Eastern Cordilleras, throughout Ecuador including Sangay and Podocarpus National Parks, and into northern Peru, notably in Cajamarca and Lambayeque.

The Mountain Tapir Tapirus pinchaque is one of the most threatened large mammals in the northern Andes, currently listed as Endangered. Their populations have declined by over 50% in the past three decades due to habitat loss, illegal hunting, climate change, and rampant mining. With fewer than 2,500 mature individuals remaining, they are quietly disappearing from their mist-shrouded mountain homes. Human encroachment, infrastructure development, and cattle grazing now invade their last strongholds. Without urgent action, they may vanish forever. Use your wallet as a weapon and fight back when you shop #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife and be #BoycottGold

Sweet-natured Mountain #Tapirs of #Ecuador 🇪🇨 #Peru 🇵🇪 and #Colombia 🇨🇴 face serious threats incl. illegal crops, #gold #mining, #palmoil #deforestation and hunting. Help them survive #BoycottPalmOil 🌴⛔️#BoycottGold 🥇⛔️ #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2025/12/28/mountain-tapir-tapirus-pinchaque/

The Wooly #Tapir AKA Mountain Tapir gives birth to one calf at a time 🩷😻 They’re #endangered due to a many threats: #climatechange and #pollution from #gold mining. Resist for them! #BoycottPalmOil #BoycottGold 🥇☠️❌ #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2025/12/28/mountain-tapir-tapirus-pinchaque/

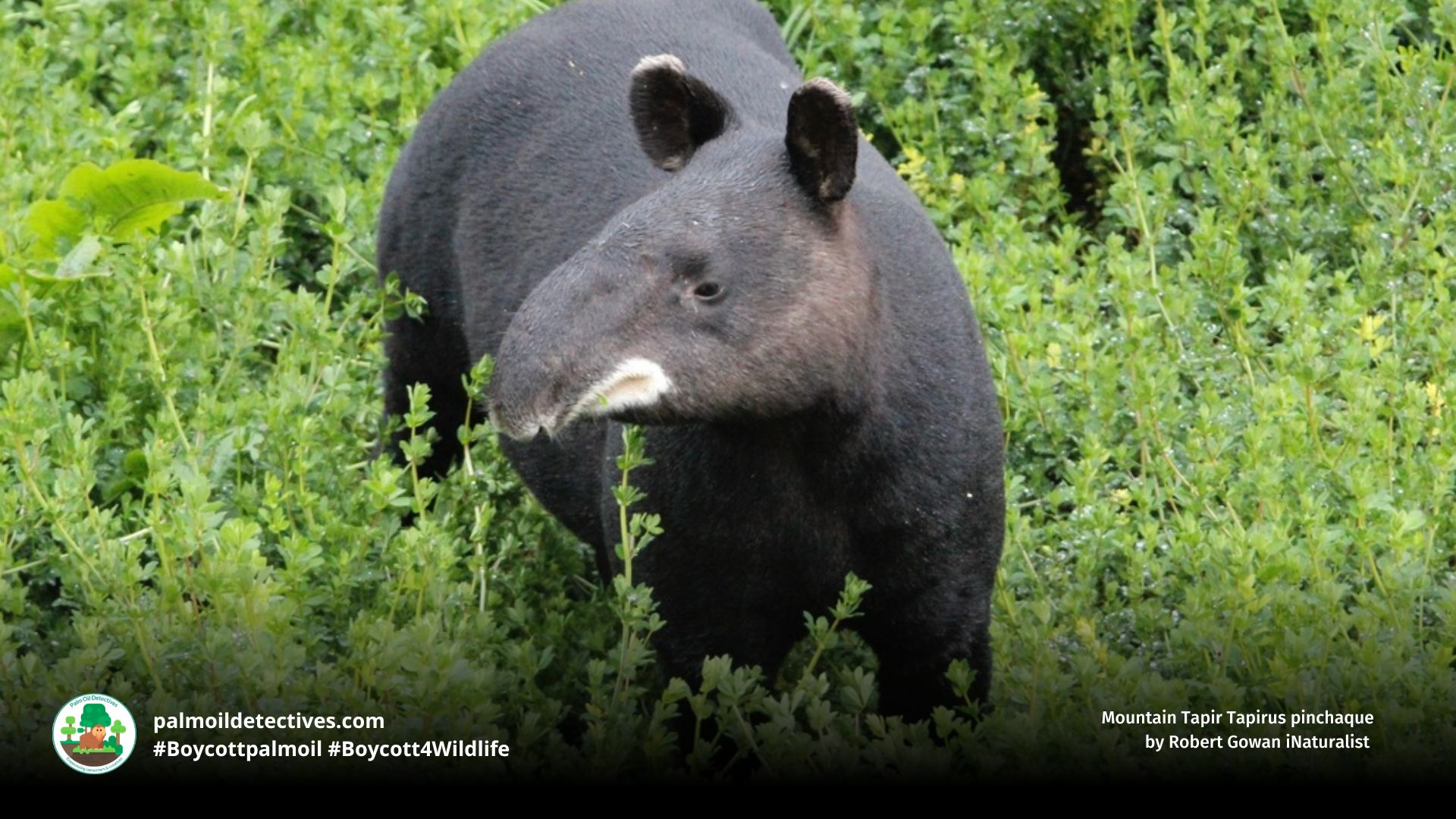

Appearance & Behaviour

Also known as the woolly tapir for their thick, dark, shaggy coat, Mountain Tapirs are built to survive in the cold, damp cloud forests and páramo grasslands. Their dense fur, white lips, and prehensile snout give them an almost prehistoric appearance. These solitary and elusive mammals are primarily nocturnal and crepuscular, navigating dense foliage with ease. Once thought to be loners, long-term studies in Ecuador have revealed that they form small, close-knit family groups, with calves gradually dispersing over several years (Castellanos et al., 2022).

Threats

Deforestation for palm oil, meat agriculture and illicit opium/coca cultivation

Large swathes of Andean cloud forest and páramo are being cleared to make way for palm oil agricultural expansion, cattle grazing, and opium or coca cultivation. These activities are not only destroying core habitat but also breaking up previously connected populations, leaving tapirs isolated and vulnerable to local extinctions. The introduction of cattle into remote tapir refuges has become increasingly common, even inside designated national parks such as Sangay in Ecuador. This leads to trampling of sensitive vegetation, direct competition for food, and destruction of the unique montane ecosystems that Mountain Tapirs rely on for survival.

Illegal hunting for meat, traditional medicine, and cultural uses

Although hunting pressure has declined slightly in Ecuador due to greater public awareness, it remains severe in Colombia and Peru. Tapirs are killed for their meat, and their skins are used to make traditional tools, horse gear, carpets, and bed covers. Additionally, body parts are sold in local markets or prescribed by shamans for use in traditional medicine. In many remote areas, Mountain Tapirs are still being actively poached, and it is now rare to find populations that are not affected by some form of overhunting.

Gold mining and illegal mining causing deforestation and poisoning of ecosystems

Gold mining projects in the northern Peruvian Andes and central Colombia are rapidly destroying the last cloud forest headwaters and páramo ecosystems where tapirs persist. Both legal and illegal mining operations contaminate streams and watersheds with heavy metals and toxic runoff, which has severe consequences for both tapirs and the human communities downstream. Mining also brings roads, noise, and human settlements into previously inaccessible areas, increasing hunting pressure and reducing available habitat. In some parts of Peru, nearly 30% of the Mountain Tapir’s current range now overlaps with active or planned gold mining concessions (More et al., 2022).

Climate change pushing tapirs further uphill into shrinking habitat

As global temperatures rise, the high-elevation ecosystems where Mountain Tapirs live are shrinking. Suitable climate zones are shifting higher up the mountains, but because mountains have limited space at the top, this forces tapirs into ever smaller areas with fewer food resources. This phenomenon, known as “the escalator to extinction,” is especially dangerous for highland species like the Mountain Tapir, who cannot move downward into warmer zones. Climate change also alters rainfall patterns and vegetation cycles, further straining the species’ delicate habitat requirements.

Road construction and vehicle collisions within protected areas

Infrastructure development is rapidly cutting through mountainous areas, including roads that bisect national parks and reserves. This not only fragments tapir habitat but also leads to direct deaths through vehicle collisions. Once roads are completed, traffic speeds increase and tapirs crossing roads—especially at dawn and dusk—become highly vulnerable. Roads also make previously remote areas more accessible to poachers, settlers, and resource extractors, while local governments often lack sufficient ranger staff to monitor and protect these newly exposed areas.

Fumigation campaigns using toxic chemicals to eradicate drug crops

In Colombia, the government authorises aerial fumigation of coca and poppy fields using glyphosate-based herbicides like Round-Up. These chemicals are sprayed over wide areas, including forests and National Parks, contaminating soil, plants, and water sources. Mountain Tapirs can absorb these toxins through skin contact or ingestion, potentially leading to illness, reproductive failure, or death. Fumigation also destroys native plants that tapirs rely on for food, further decreasing habitat quality in affected areas.

Widespread introduction of cattle and the threat of disease transmission

Domestic cattle are increasingly being introduced into mountain tapir habitat, especially within protected areas where enforcement is weak. These animals not only compete with tapirs for forage but also carry diseases such as bovine tuberculosis and foot-and-mouth disease. Disease outbreaks have already been documented among tapirs in other parts of Latin America and pose a serious threat to small, isolated populations. In the Andes, cattle often form feral herds that reproduce and spread deep into cloud forests, further eroding habitat integrity and increasing the risk of tapir extinction.

Weak enforcement of environmental laws and lack of large protected areas in Peru

Although some Mountain Tapir habitat falls within designated protected areas, law enforcement in Peru is generally under-resourced and poorly coordinated. Rangers are too few to patrol vast mountainous regions effectively, and illegal activities such as mining, logging, and hunting continue within protected boundaries. Furthermore, most reserves are too small or fragmented to support viable tapir populations over the long term. Without stronger policies, larger protected zones, and meaningful binational cooperation with Ecuador and Colombia, tapirs in Peru face an uncertain future.

Low reproductive rate and slow population recovery

Mountain Tapirs have a long gestation period of around 13 months and typically produce only one calf at a time, meaning population growth is inherently slow. When combined with high mortality from hunting, roadkill, and disease, their populations cannot recover quickly from losses. Calves stay with their mothers for extended periods, further limiting reproductive output. This slow life cycle makes the species particularly vulnerable to sudden or sustained threats across their fragmented range.

Geographic Range

This species is found in the high Andes of Colombia, Ecuador, and northernmost Peru. In Colombia, they are present in the Central and Eastern Cordilleras but are absent from the Western Cordillera and Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. In Ecuador, they range from the central Andes down through Sangay National Park to Podocarpus, with new records emerging from previously unconnected areas in the western Andes. In Peru, they occur north and south of the Huancabamba River in Cajamarca and Lambayeque (More et al., 2022). The total range in Peru is estimated at 183,000 hectares, but mining concessions cover nearly 30% of this habitat.

Diet

Mountain Tapirs are browsers, feeding on a wide variety of vegetation including leaves, shoots, fruits, and bromeliads. Their diet varies depending on the availability of plants within their high-altitude habitats, playing an important role as seed dispersers within these fragile ecosystems.

Mating and Reproduction

Mountain Tapirs have a slow reproductive rate, with a gestation period of approximately 13 months. Females typically give birth to a single calf, which stays with them for several months or even years before dispersing. Calves are born with white stripes and spots that fade as they mature. Their slow breeding cycle makes it difficult for populations to recover from hunting and habitat loss.

FAQs

How many Mountain Tapirs are left in the wild?

Fewer than 2,500 mature individuals remain in the wild, and the population is continuing to decline by at least 20% every two decades due to ongoing threats like habitat destruction, hunting, and climate change (IUCN, 2015).

What is the average lifespan of a Mountain Tapir?

In the wild, Mountain Tapirs may live up to 25 years, though this is significantly affected by environmental threats. Captive individuals can live slightly longer under safe and controlled conditions.

What are the biggest challenges to conserving Mountain Tapirs?

Major challenges include habitat fragmentation due to road construction, agriculture, and mining; the presence of armed conflict zones that hinder research and protection; and the slow reproduction rate of the species, which makes population recovery difficult (Guzmán-Valencia et al., 2024; More et al., 2022).

Do Mountain Tapirs make good pets?

No. Keeping a Mountain Tapir as a pet is unethical and illegal. These intelligent, solitary animals require large, wild habitats to survive. Capturing and trading them causes immense suffering and drives the species further toward extinction. Advocating against the exotic pet trade is vital to their survival.

Take Action!

Boycott palm oil and products linked to Andean deforestation. Support indigenous-led conservation and agroecology initiatives in the Andes. Call for stronger protections against mining and deforestation in Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. Refuse to buy exotic animal products, including those used in folk medicine. #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife #Vegan #BoycottMeat

Support Mountain Tapirs by going vegan and boycotting palm oil in the supermarket, it’s the #Boycott4Wildlife

Support the conservation of this species

This animal has no protections in place. Read about other forgotten species here. Create art to support this forgotten animal or raise awareness about them by sharing this post and using the #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife hashtags on social media. Also you can boycott palm oil in the supermarket.

Further Information

Castellanos, A., Dadone, L., Ascanta, M., & Pukazhenthi, B. (2022). Andean tapir (Tapirus pinchaque) social groups and calf dispersal patterns in Ecuador. Boletín Técnico, Serie Zoológica, 17, 9–14. Retrieved from https://journal.espe.edu.ec/ojs/index.php/revista-serie-zoologica/article/view/2858

Delborgo Abra, F., Medici, P., Brenes-Mora, E., & Castelhanos, A. (2024). The Impact of Roads and Traffic on Tapir Species. In Tapirs of the World (pp. 157–165). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-65311-7_10

Guzmán-Valencia, C., Castrillón, L., Roncancio Duque, N., & Márquez, R. (2024). Co-Occurrence, Occupancy and Habitat Use of the Andean Bear and Mountain Tapir: Insights for Conservation Management in the Colombian Andes. SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5061561

Lizcano, D.J., Amanzo, J., Castellanos, A., Tapia, A. & Lopez-Malaga, C.M. 2016. Tapirus pinchaque. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T21473A45173922. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T21473A45173922.en. Accessed on 06 April 2025.

More, A., Devenish, C., Carrillo-Tavara, K., Piana, R. P., Lopez-Malaga, C., Vega-Guarderas, Z., & Nuñez-Cortez, E. (2022). Distribution and conservation status of the mountain tapir (Tapirus pinchaque) in Peru. Journal for Nature Conservation, 66, 126130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2022.126130

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Learn about other animals endangered by palm oil and other agriculture

Learn about “sustainable” palm oil greenwashing

Read more about RSPO greenwashing

A 2019 World Health Organisation (WHO) report into the palm oil industry and RSPO finds extensive greenwashing of palm oil deforestation and the murder of endangered animals (i.e. biodiversity loss)

Discover more from Palm Oil Detectives

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.