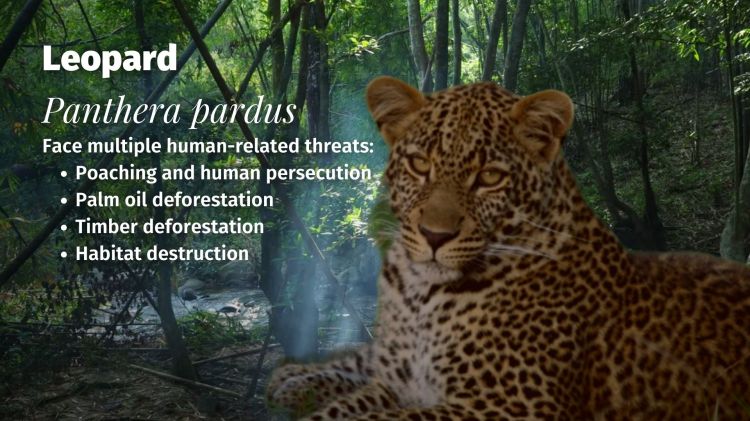

Leopard Panthera pardus

IUCN Status: Vulnerable

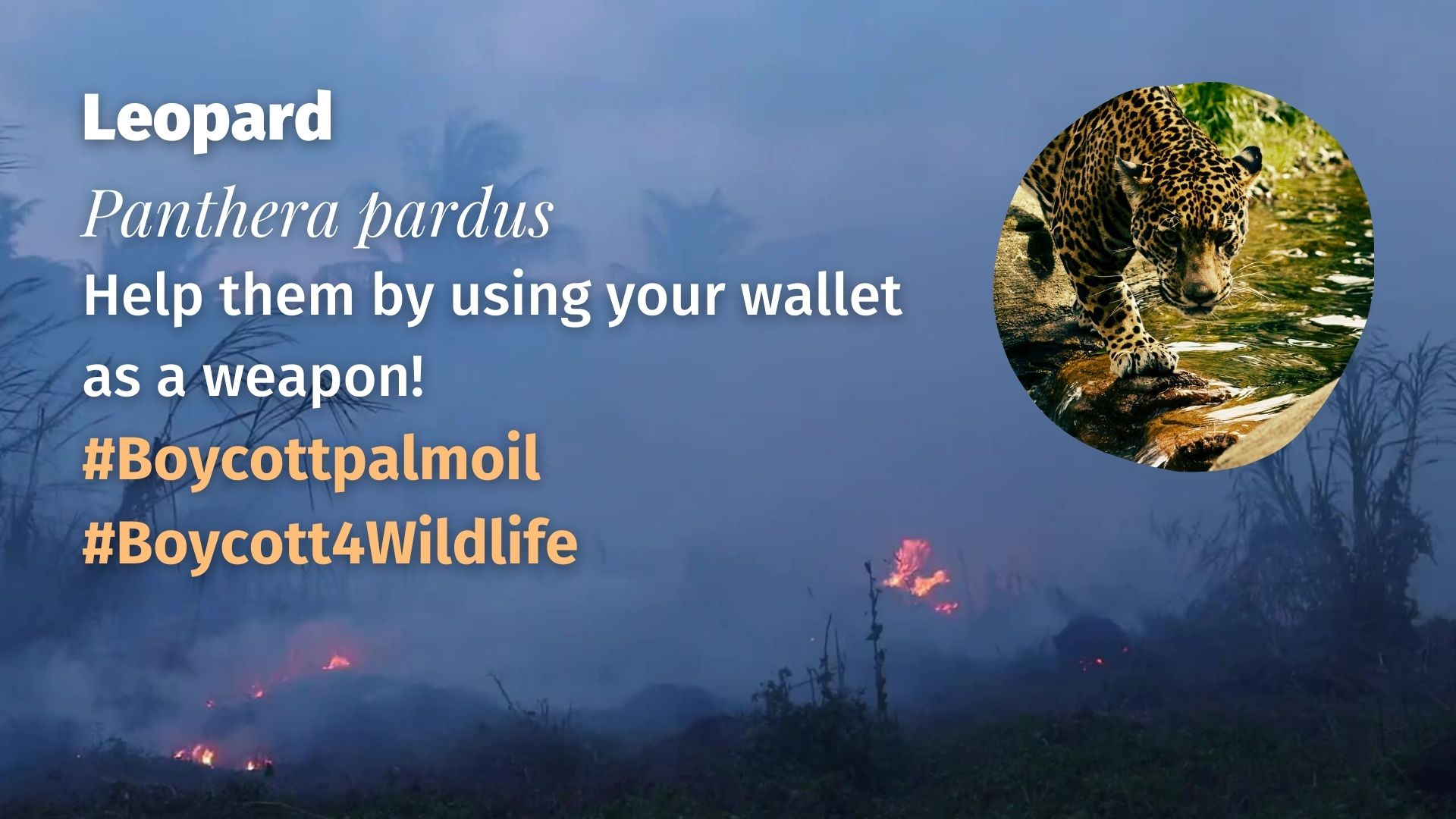

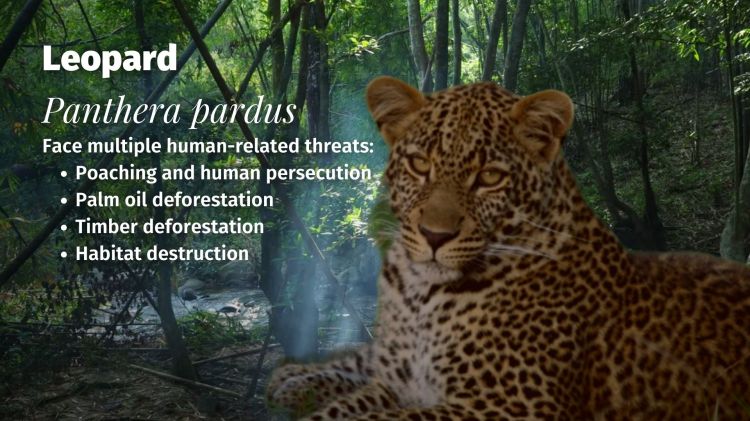

Of all the big cats prowling the wild, few inspire as much awe and fascination as the leopard Panthera pardus. Sleek, powerful, and enigmatic, leopards are found across a staggering range—from sub-Saharan Africa, forests of West Africa and the Middle East to Central Asia and the forests of Southeast Asia. Yet this extraordinary adaptability masks a disturbing truth. The leopard is currently listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List, with some subspecies such as the Amur, Arabian, and Javan leopard are on the very brink of extinction. Across their range, these elusive big cats are being driven into ever-shrinking patches of habitat, with populations decimated by deforestation, rampant poaching, prey depletion, and the relentless spread of palm oil plantations and other monoculture. Help leopards every time you shop and #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife

Sleek and splendid jungle royalty – #leopards 🐆💛 are adaptable, yet are now #extinct in places due to #palmoil #deforestation, #poaching and other threats. Fight for them in the supermarket and be #vegan #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://wp.me/pcFhgU-199

Majestic #leopards are adaptable and a range over several continents, yet they’re #extinct in places due to #palmoil #deforestation, #poaching and other threats. Help them every time you shop and #Boycottpalmoil 🌴🚫#Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://wp.me/pcFhgU-199

Living: (Parts of) Central and Southern Africa, The Middle East, Southern Asia, Indonesia, Malaysia.

Possibly Extinct: Gambia; Israel; Korea, Democratic People’s Republic of; Lao People’s Democratic Republic; Lesotho; Tajikistan; Viet Nam

Extinct: Hong Kong; Jordan; Korea, Republic of; Kuwait; Lebanon; Mauritania; Morocco; Singapore; Syrian Arab Republic; Togo; Tunisia; United Arab Emirates; Uzbekistan

The primary threats to Leopards are anthropogenic. Deforestation for agriculture and mining, reduced prey base and human conflict have reduced Leopard populations throughout most of their range (Nowell and Jackson 1996, Ray et al. 2005, Hunter et al. 2013).

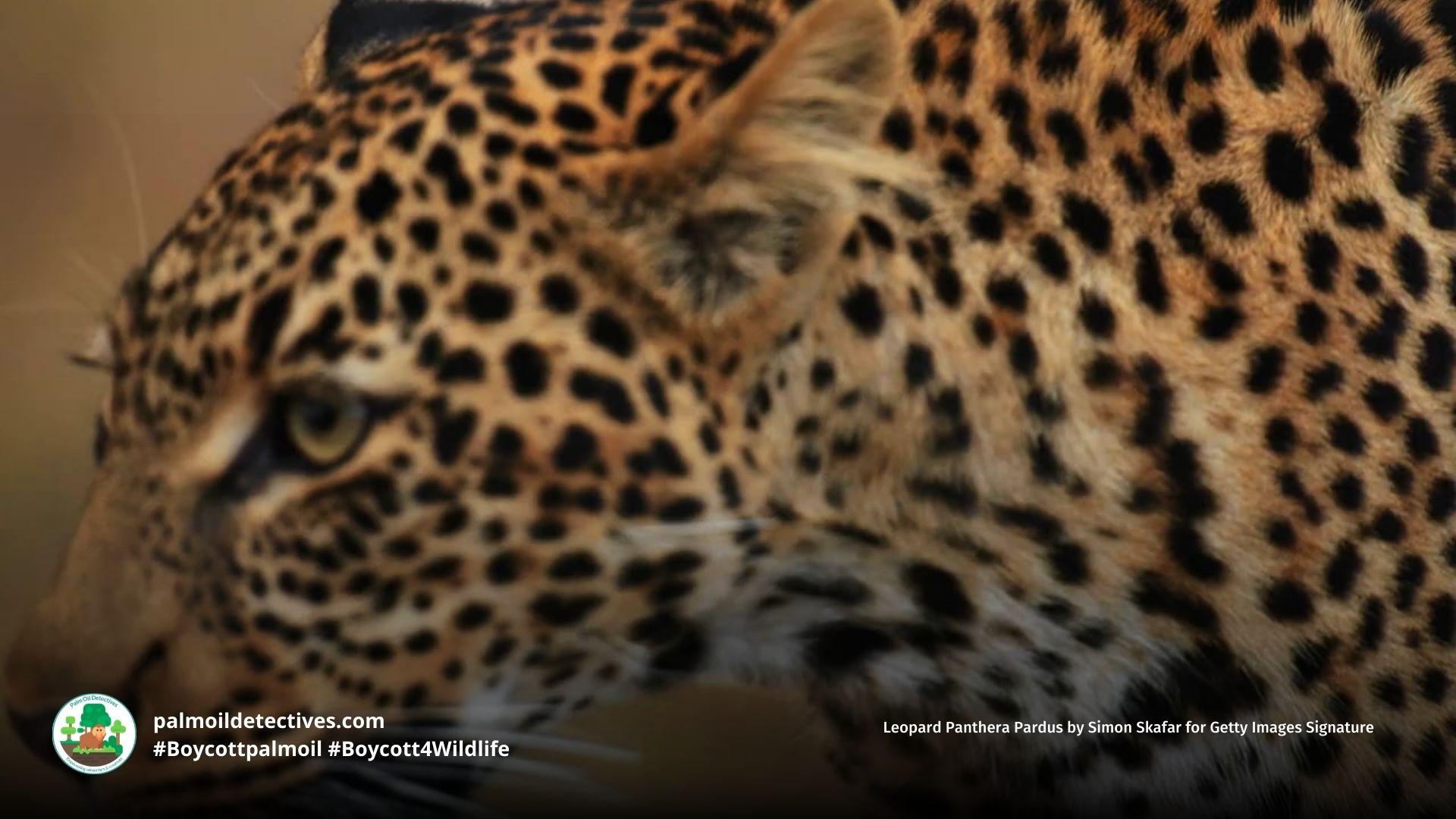

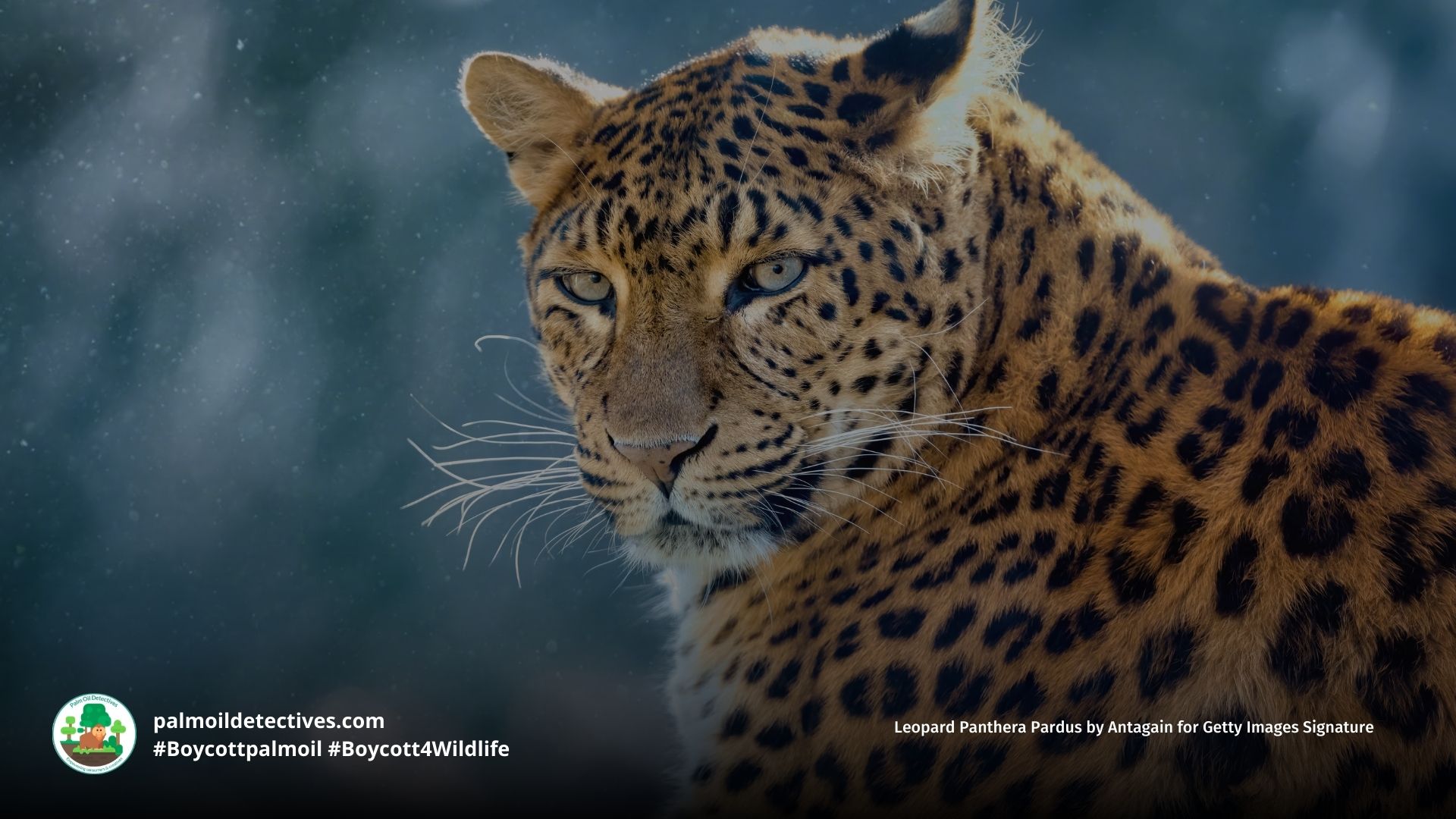

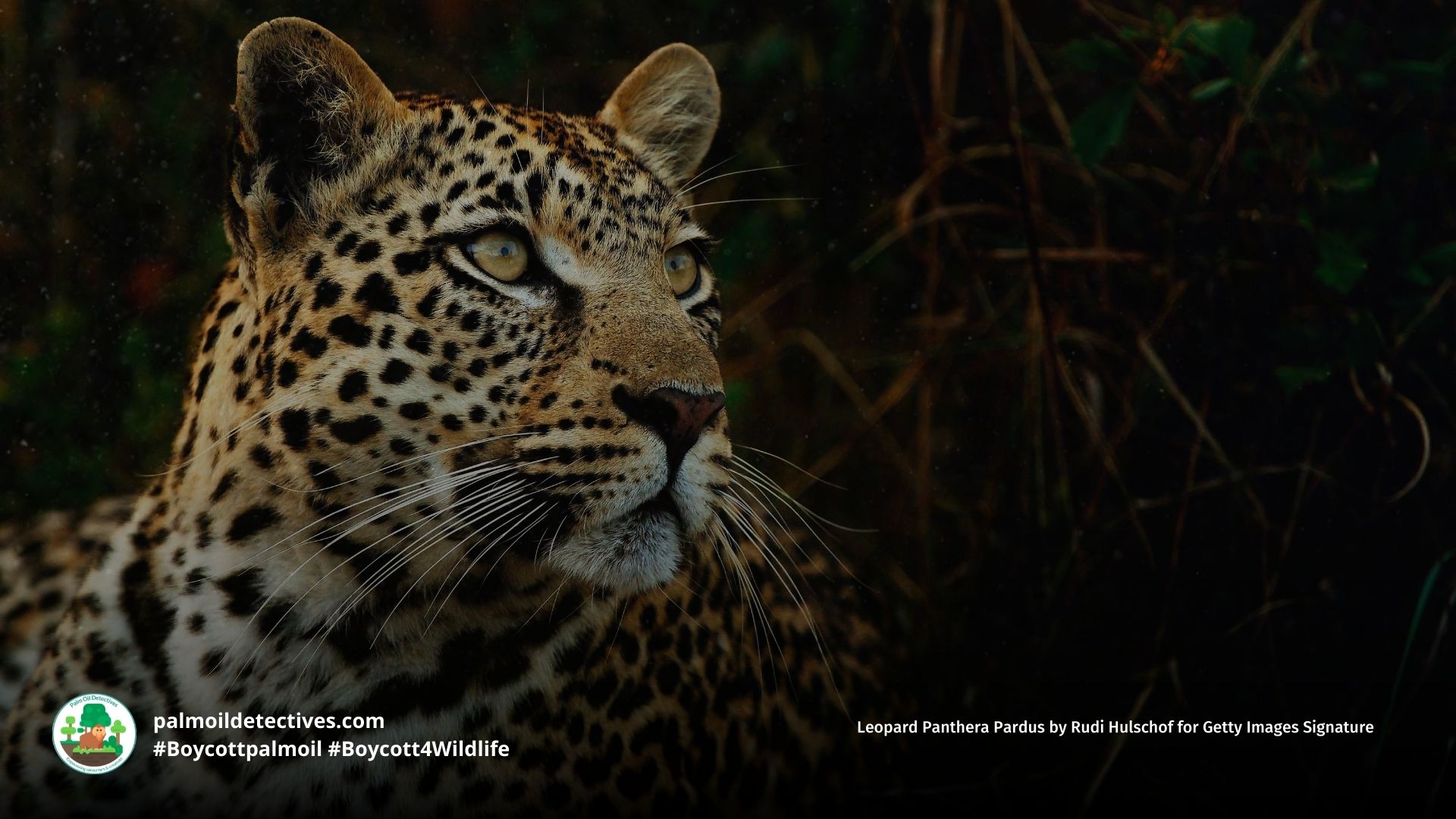

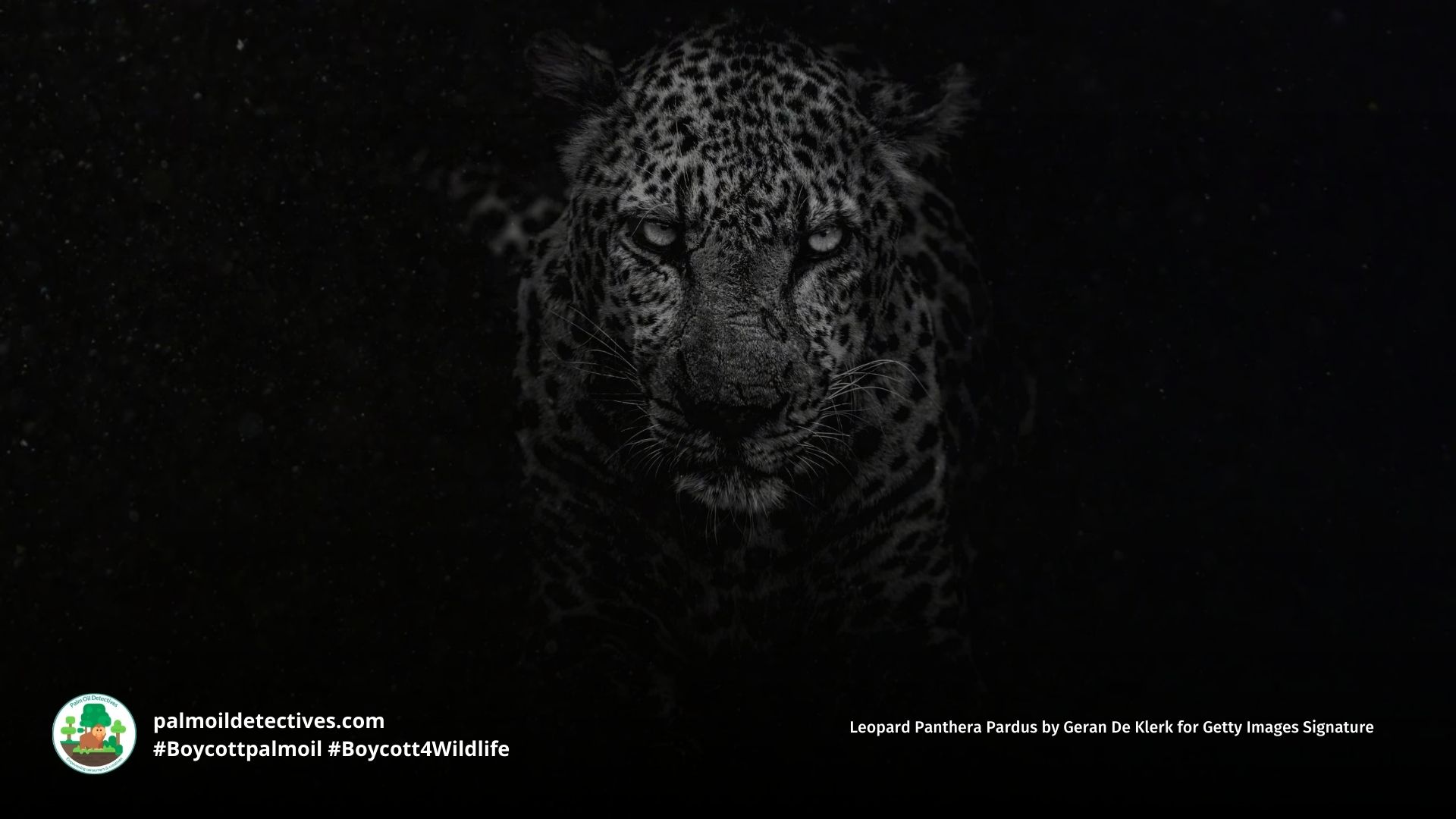

Appearance and Behaviour

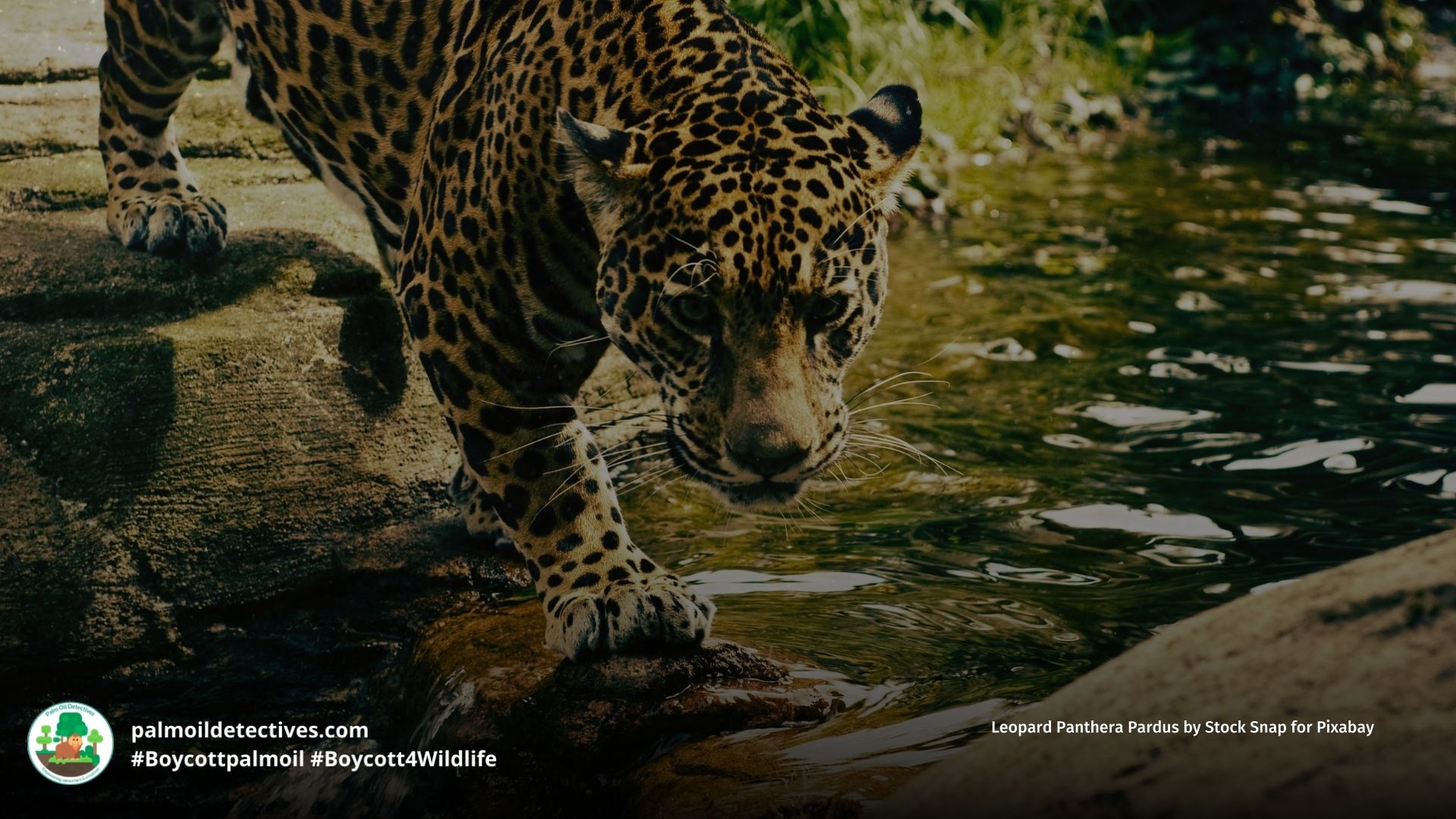

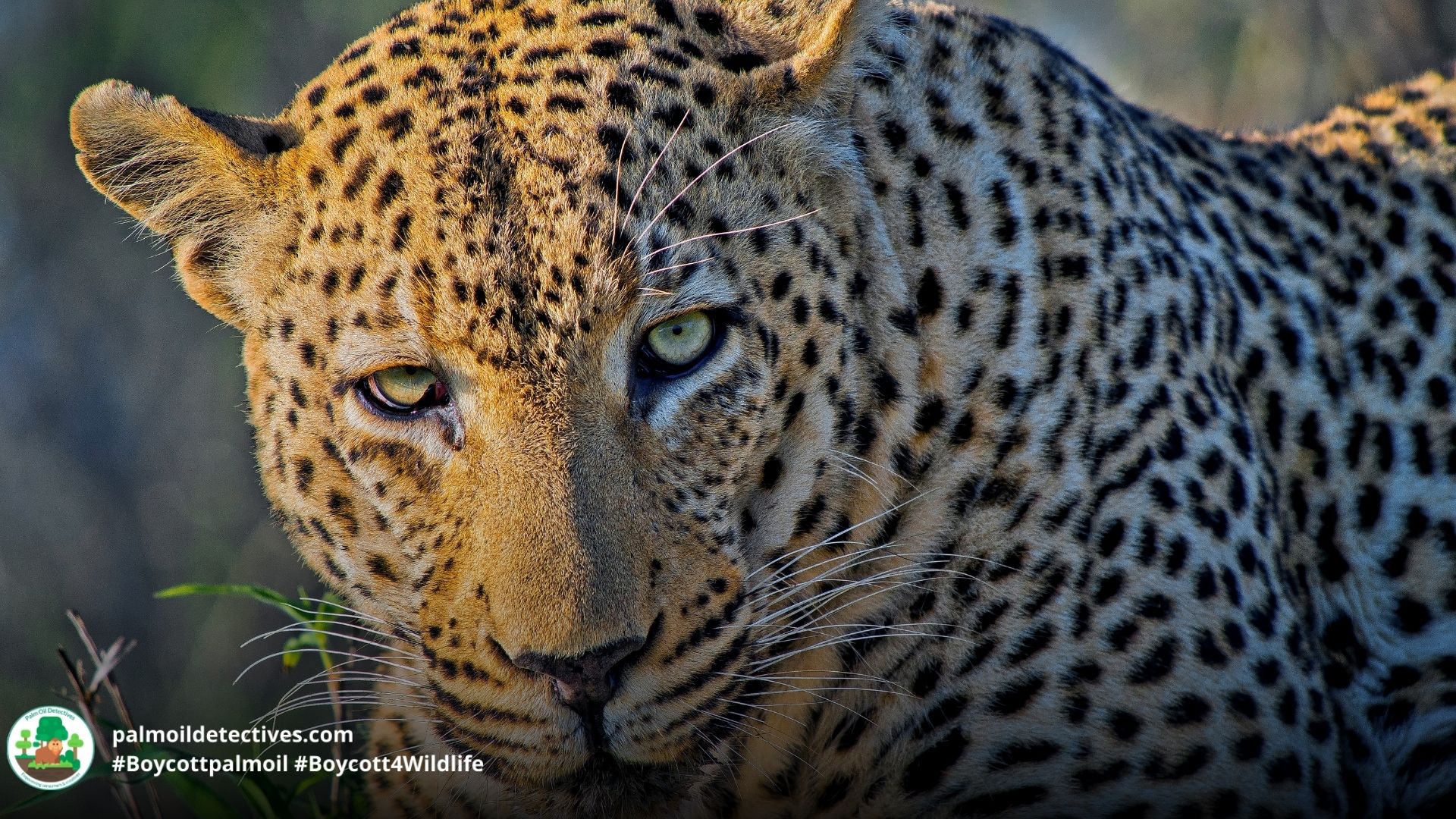

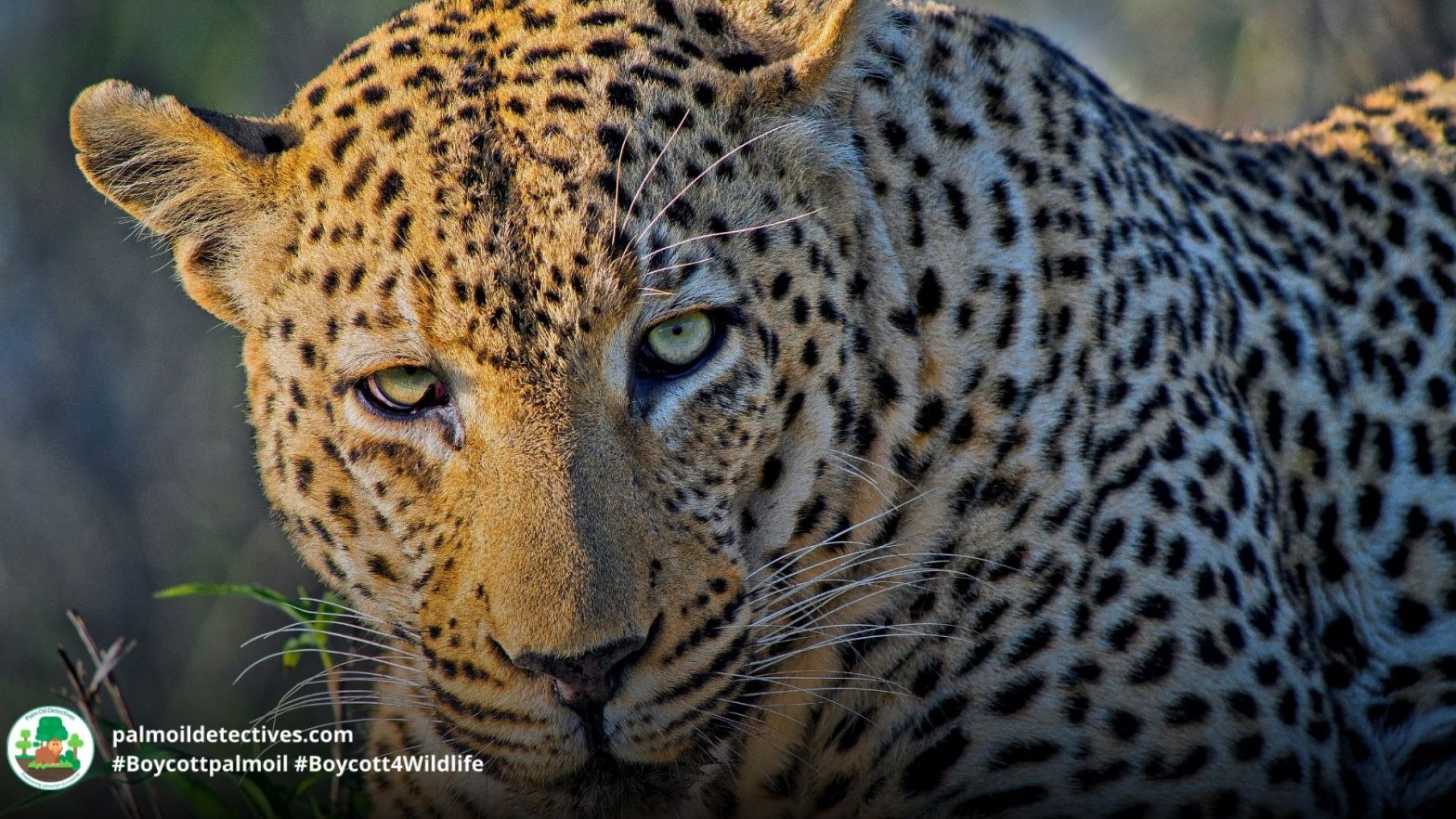

Every leopard wears a coat unlike any other— with their rosettes and spots forming a one-of-a-kind constellation across golden, ochre, or charcoal fur. The beauty of these big cats is captivating, their gaze watchful and calculating.

Built to blend in

Their golden-yellow to pale ochre fur blends seamlessly into grasslands and forests, while leopards in colder or wetter habitats often appear darker or more greyish. This camouflage is key to their stealthy hunting behaviour. Melanistic leopards—commonly called black leopards or erroneously called black panthers—also occur, especially in rainforest regions.

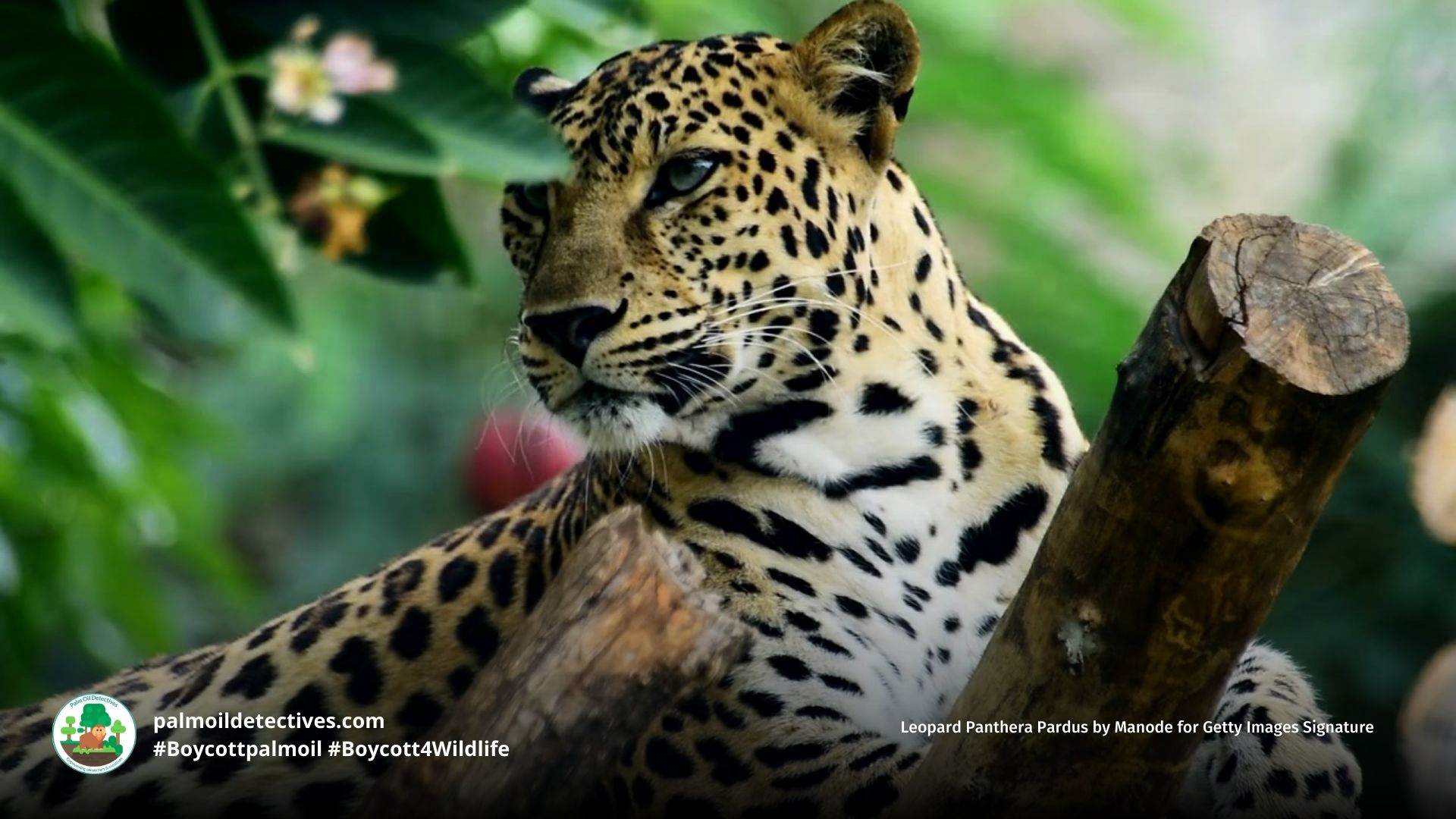

Built for explosive predatory power

Built for stealth, leopards possess a combination of muscular grace and explosive power that allows them to leap six metres horizontally or drag prey twice their weight into the boughs of trees. Males are typically larger, weighing between 60 to 90 kilograms, while females range from 35 to 45 kilograms. Their bodies are compact and athletic, crowned with a long tail that helps with balance when climbing or navigating rough terrain.

Highly complex social communities are important

Though often described as solitary, recent research reveals a surprisingly complex social life behind the scenes. A 2023 study by Verschueren et al. uncovered evidence of structured social networks in leopards, suggesting that even these famously aloof cats form stable social units. Within these, same-sex and opposite-sex interactions occur regularly, and individuals appear to engage in temporal segregation—essentially taking turns using the same spaces at different times. Some leopards, known as ‘central individuals,’ maintain connections within and outside of their group, playing a key role in keeping their small communities stable. When such individuals are killed—often by trophy hunters or in retaliation for livestock losses—the social fabric of an entire local population can unravel.

Solitary yet highly social

Territorial by nature, leopards scent-mark and vocalise with a characteristic sawing call to define and defend their domains. Females maintain smaller, overlapping ranges often adjacent to their mothers’, while males tend to roam over much larger areas that may overlap with several female territories. Mating encounters can be prolonged and intense—filled with dramatic vocalisations, flirtatious circling, and frequent couplings over several days.

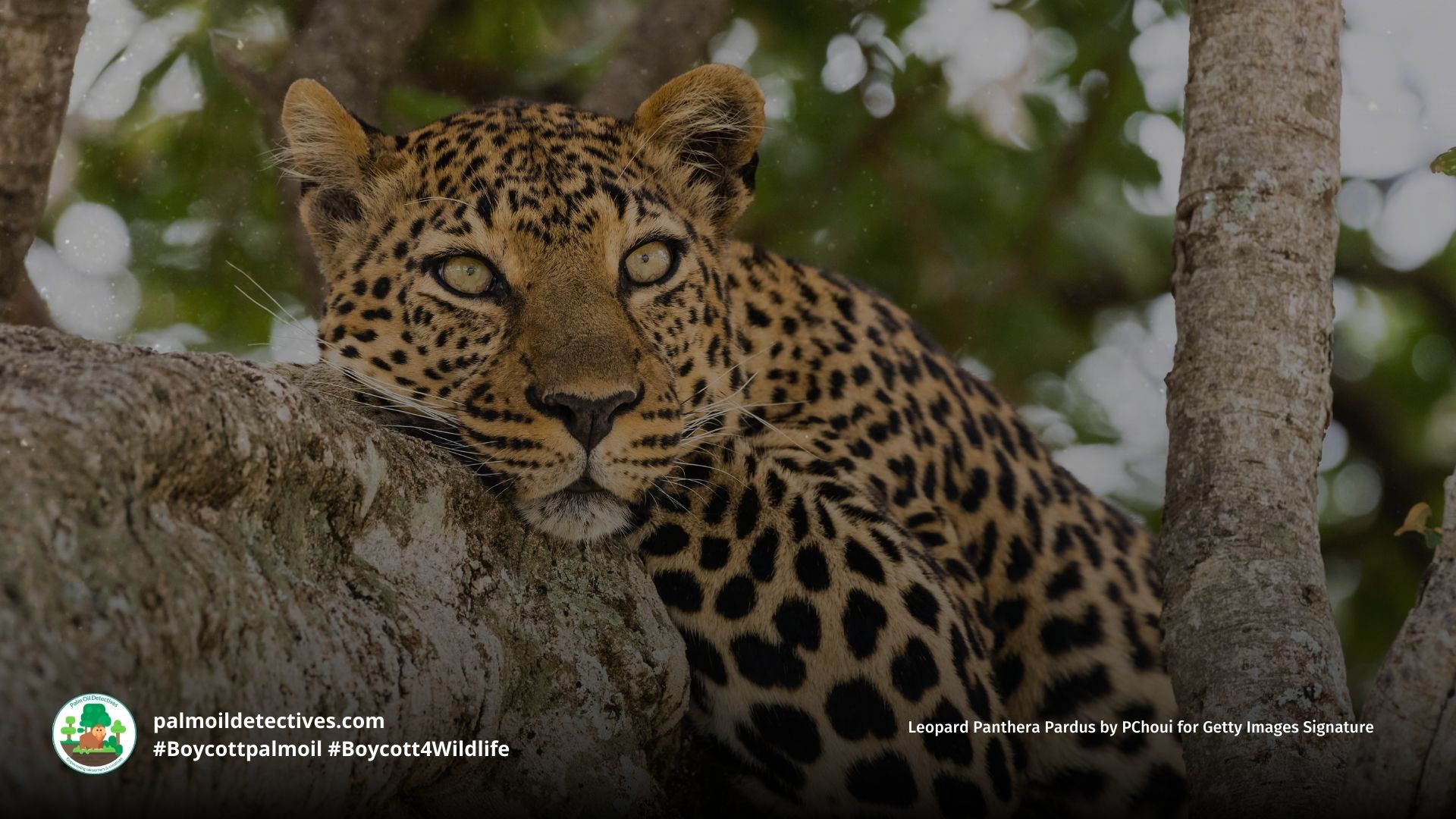

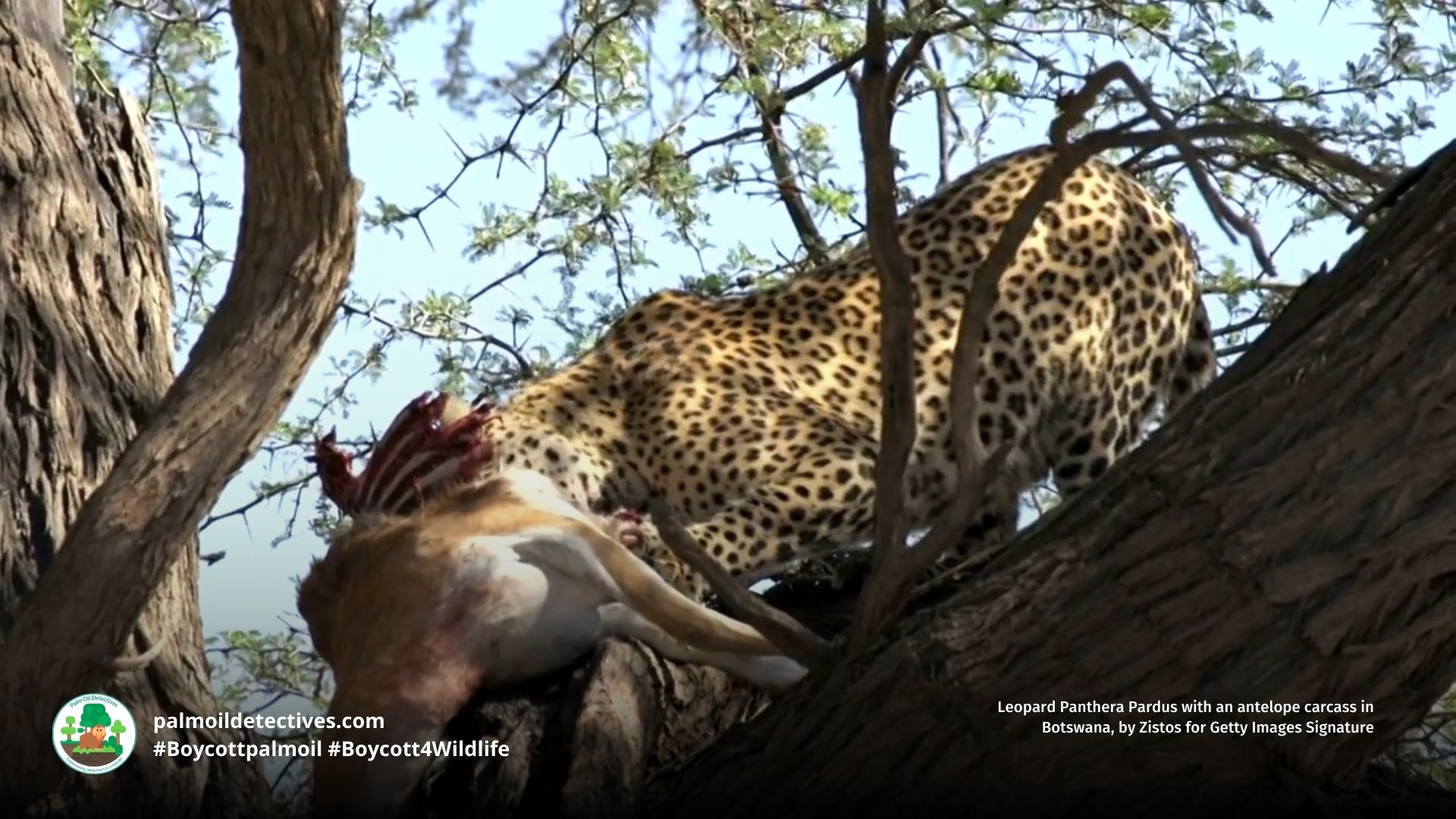

Hoisting prey into trees helps them avoid scavengers

Highly solitary and territorial, leopards are typically nocturnal but can be active at any time of day. They are agile climbers, often hoisting their prey into trees to avoid scavengers. They communicate through scent-marking, vocalisations like sawing calls, and claw scraping. Remarkably adaptive, leopards can survive in urban fringes, deserts, alpine zones, and tropical forests.

Leopard Photography below by Dalida Innes

Diet

Leopards are opportunistic carnivores with the broadest diet among large cats, consuming over 100 prey species. These include medium-sized ungulates such as impala, bushbuck, chital, wild boar, and livestock. They also eat primates, birds, reptiles, small mammals, and even insects. In human-dominated areas, dogs and goats become common prey, often exacerbating conflict.

Caching kills in trees or dense vegetation is common, particularly in regions where competition with lions, hyenas, or tigers is high. This strategy allows leopards to return to large carcasses over several days, safe from scavengers. Their hunting relies on stealth and powerful ambush attacks.

Reproduction and Mating

Leopards are polygynous, with mating possible year-round in most regions. Gestation lasts 90–105 days, after which females give birth to 2–4 cubs in secluded dens. Cubs stay with their mother for up to two years, learning to hunt and survive.

Infanticide by rival males is a major cause of cub mortality, along with predation by lions, hyenas, and other carnivores. Reproductive age begins around 2.5 years, and the average generation length is estimated at 9.3 years. In captivity, leopards can live over 20 years, though the average wild lifespan is 12–17 years.

Geographic Range

Leopards once roamed across nearly all of Africa and much of Asia, but now occupy only 25–37% of their historic range. Subspecies distributions vary:

- African leopard (P. p. pardus) – Found across Sub-Saharan Africa; declining due to prey depletion and conflict.

- Indian leopard (P. p. fusca) – Widely spread in India; frequent conflict with humans and poaching.

- Javan leopard (P. p. melas) – Endemic to Java; fewer than 250 breeding adults remain.

- Amur leopard (P. p. orientalis) – Russian Far East; under 60 individuals remain.

- Arabian leopard (P. p. nimr) – Oman and Yemen; 100–120 individuals remain.

- Persian leopard (P. p. saxicolor) – Iran, Turkey, Caucasus; <1,000 individuals.

- Sri Lankan leopard (P. p. kotiya) – 700–950 estimated.

- Indochinese leopard (P. p. delacouri) – Southeast Asia; heavily impacted by poaching.

- North Chinese leopard (P. p. japonensis) – Fewer than 500 individuals remain.

Populations are highly fragmented and often isolated, with extirpations in North Africa, Singapore, much of the Middle East, and large parts of Southeast Asia.

Threats

Deforestation in South-east Asia has increased for palm oil and rubber plantations (Sodhi et al. 2010, Miettinen et al. 2011). These factors were not incorporated in the previous assessment and likely have a substantial impact on suitable Leopard range.

IUCN red LIst

Habitat Loss and Fragmentation

Leopard habitats are being rapidly converted to agriculture, livestock grazing, roads, and urban expansion. From 1975 to 2000, potential leopard habitat declined by 57% in Africa, particularly in West Africa and North Africa. In Southeast Asia, palm oil and rubber plantations have erased vast tracts of forest. Leopards in India, though still widespread, are often confined to forest islands amid human settlements.

Prey Depletion

Bushmeat hunting has decimated prey populations. Between 1970 and 2005, prey species declined by 59% in 78 African protected areas (Craigie et al., 2010). West and East Africa have seen the worst collapses. In Asia, wild ungulates like Sambar deer are disappearing across tropical forest systems, further threatening leopard survival.

Illegal Wildlife Trade

Leopards are poached for their skins and body parts, often for traditional ceremonies or as tiger substitutes in traditional medicine. In India, at least four leopards per week were poached between 2002 and 2012. In southern Africa, up to 7,000 leopards may be killed annually to supply leopard skins to the Shembe Church (Balme, unpub. data). In Morocco, dozens of skins were found in just two surveys.

Trophy Hunting

Though regulated under CITES, trophy hunting quotas are often based on outdated models. In Zimbabwe, poorly managed trophy hunting, bushmeat snares, and high lion densities (>6/100km2) significantly lowered leopard densities to as few as 0.7 leopards/100km2 in some areas (Loveridge et al., 2022). South Africa temporarily banned leopard trophy hunting in 2016 due to poor population data.

Conflict with Humans

Leopards are frequently killed in retaliation for livestock attacks. Conflict is especially high in India, where leopards often venture into human settlements. In northern Iraq and parts of Iran, unsustainable leopard killing continues in retribution for livestock depredation (Raza et al., 2012).

Subspecies-Specific Threats

- Amur leopard: <60 individuals, impacted by forest fragmentation, poaching, and low genetic diversity.

- Arabian leopard: Endemic to Oman and Yemen; threatened by poaching and habitat degradation.

- Indochinese leopard: Functionally extinct in Laos and Vietnam due to poaching and deforestation.

- Javan leopard: Critically Endangered; primary threats are habitat loss and illegal trade.

- North Chinese leopard: <500 individuals remain, fragmented across reserves.

Take Action!

The leopard’s survival depends on our choices. Avoid products linked to deforestation—especially palm oil. Support indigenous-led conservation and efforts to protect habitat and prey species. Oppose trophy hunting and illegal wildlife trade and actively campaign online against this. Advocate for wildlife corridors and coexistence strategies.

Use your wallet as a weapon for vulnerable leopards and for big cats all over the world. Every time you shop make sure you #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife adopt a #Vegan lifestyle and actively join the online campaign to #BanTrophyHunting

FAQs

How many leopards are left in the wild?

No global population estimate exists for leopards due to significant data gaps and their elusive natures. However, detailed studies of specific subspecies highlight an alarming trend. The Amur leopard (Panthera pardus orientalis), for example, is critically endangered with fewer than 60 individuals left in the wild. The Arabian leopard (P. p. nimr) has only 100 to 120 individuals in isolated populations across Oman and Yemen. The Javan leopard (P. p. melas), endemic to Indonesia, is estimated to have fewer than 250 wild individuals remaining. In contrast, the Indian leopard (P. p. fusca) has a relatively larger population of around 12,000 to 14,000 individuals, yet even they are under constant threat. Overall, leopards now occupy just 25% of their historical range, and localised extinctions are accelerating across Africa and Asia.

How long do leopards live?

Leopards generally live between 12 and 17 years in the wild, depending on factors such as prey availability, conflict with humans, and the presence of rival predators. In captivity, where threats are minimised, leopards can live up to 24 years. However, captivity cannot replicate the ecological complexity or the freedom of their wild habitats, which are vital for their well-being and natural behaviours.

Why are leopards disappearing?

Leopards are vanishing due to a toxic mix of human pressures. Habitat loss from deforestation, agriculture, and urban expansion is the single most significant threat. Leopards also suffer from prey depletion caused by unsustainable bushmeat hunting, especially in Africa where prey species in protected areas have declined by an average of 59%. Poaching for the illegal wildlife trade is rampant—leopards are killed for their skins, bones, and teeth. In India, an average of four leopards are poached each week. In Africa, ceremonial skin use, particularly among the Shembe Church in southern Africa, results in the deaths of thousands annually (Balme et al., unpublished data). Poorly managed trophy hunting has also devastated local populations, especially where outdated population models continue to inform CITES quotas.

Are leopards affected by palm oil plantations?

Yes, and the impact is devastating. The rapid spread of palm oil and rubber plantations in Southeast Asia has destroyed vast tracts of primary rainforest—habitats critical to the survival of Javan and Indochinese leopards. These forest-specialist subspecies rely on dense, biodiverse ecosystems for hunting, breeding, and shelter. Studies have shown that over 70% of native forests in parts of Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand have been cleared, largely to make way for monoculture plantations. With their habitat fragmented and prey vanishing, these leopards face extinction. #BoycottPalmOil and support indigenous-led conservation to protect what remains.

Is leopard poaching still happening?

Yes—on a staggering scale. Despite CITES Appendix I protections, illegal trafficking continues unabated. Skins are sold for ceremonial use, particularly in parts of southern Africa and Asia. Bones and claws are used in traditional medicine or as trophies. According to studies, India loses at least four leopards a week to poaching (Raza et al., 2012), while surveys in Morocco have documented leopard skins openly sold in urban markets (Kumar et al., 2017). Seizures of leopard parts are common across Asia, and online trade remains widespread. In sub-Saharan Africa, particularly South Africa, Botswana, and Zimbabwe, the trade in leopard skins for cultural regalia contributes heavily to the pressure on already-declining populations. With few deterrents and weak enforcement, poaching remains a major threat across the leopard’s global range.

Do leopards make good pets?

No. Leopards are wild apex predators, not domesticated animals. They have complex behavioural needs, vast territorial ranges, and require solitude. Keeping a leopard as a pet not only leads to severe psychological and physical distress for the animal but also fuels the illegal pet trade and pushes wild populations further toward extinction. Many so-called ‘pet’ leopards are stolen as cubs after their mothers are killed. These cubs are then sold into the exotic animal trade, where they are confined, abused, and deprived of everything natural to them. Keeping leopards as pets is a form of cruelty and exploitation—one that contributes directly to the collapse of wild populations. Advocate against exotic pet ownership and support efforts to keep wild animals in the wild where they belong.

There is no global population estimate due to data gaps, but some subspecies are critically endangered with populations under 100. The Indian leopard is estimated at 12,000–14,000 individuals (Bhattacharya, 2015). Amur leopards number fewer than 60.

Support the conservation of this species

Stein, A.B., Athreya, V., Gerngross, P., Balme, G., Henschel, P., Karanth, U., Miquelle, D., Rostro-Garcia, S., Kamler, J.F., Laguardia, A., Khorozyan, I. & Ghoddousi, A. 2020. Panthera pardus (amended version of 2019 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T15954A163991139. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-1.RLTS.T15954A163991139.en. Downloaded on 09 March 2021.

Further Information

Africa Geographic. (n.d.). Leopards – Silent, secretive and full of surprises. Africa Geographic. Retrieved April 19, 2025, from

https://africageographic.com/stories/leopards-silent-secretive-and-full-of-surprises/

Dalida Innes Wildlife Photography

Jacobson, A. P., et al. (2016). Leopard (Panthera pardus) status, distribution, and the research efforts across its range. PeerJ, 4, e1974. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1974

Mitchell, C., Bolam, J., Bertola, L. D., Naude, V. N., Gonçalves da Silva, L., & Razgour, O. (2024). Leopard subspecies conservation under climate and land‐use change. Ecology and Evolution, 14(5), e11391. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.11391

Loveridge, A. J., et al. (2022). Environmental and anthropogenic drivers of African leopard Panthera pardus population density. Biological Conservation, 272, 109641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109641

Raza, R. H., et al. (2012). Illuminating the blind spot: A study on illegal trade in leopard parts in India. TRAFFIC India Report. https://www.traffic.org/publications/reports/illuminating-the-blind-spot-a-study-on-illegal-trade-in-leopard-parts-in-india/

Verschueren, S., Fabiano, E. C., Nghipunya, E. N., Cristescu, B., & Marker, L. (2023). Social organization of a solitary carnivore, the leopard, inferred from behavioural interactions at marking sites. Animal Behaviour, 200, 115–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2023.03.019

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Leopard. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leopard

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Discover more from Palm Oil Detectives

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Leopard Panthera pardus”