Ecuadorian White-fronted Capuchin Cebus aequatorialis

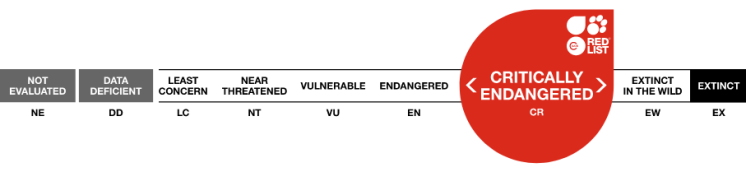

Red List status: Critically Endangered

Locations: Western lowland Ecuador (Esmeraldas, Manabí, Guayas, Los Ríos, Santa Elena provinces) and extreme north-west Peru (Tumbes, Piura). The Ecuadorian White-fronted Capuchin survives in fragments of coastal dry forest and humid foothill woodland.

The Ecuadorian White-fronted Capuchin is a clever, social monkey, once a common sight in Ecuador’s lush coastal forests. Today, their world is shattered—over 90% of their habitat has vanished to palm oil, cattle, and soy. Chainsaws, fire, and bulldozers have left only scattered islands of green. Farmers shoot capuchins for raiding crops, hunters snatch infants for the illegal pet trade, and #mining operations poison the streams where they once drank. Now, fewer than ten thousand remain. Stand with indigenous communities defending the last forests. Use your wallet as a weapon. #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife #Vegan

Ecuadorian White-fronted #Capuchins 🐒 are critically #endangered #monkeys of #Peru 🇵🇪 #Ecuador 🇪🇨. Threats: #palmoil and #meat #deforestation and hunting. Help them when you shop, be #vegan 🫑🍉#BoycottPalmOil 🌴🩸⛔️ #Boycott4Wildlife https://palmoildetectives.com/2021/10/23/ecuadorian-white-fronted-capuchin-cebus-aequatorialis/ @palmoildetect

Appearance and Behaviour

The Ecuadorian White-fronted #Capuchin is a medium sized monkey with light brown back and white underside, giving this species its alternative name of Ecuadorian White-fronted Capuchin. This species is very similar to other species of white-fronted capuchin, and was only classified as a separate species in 2013.

The Ecuadorian White-fronted Capuchin is a medium-sized primate, measuring 35–50 cm with a tail of equal length and weighing 2–4 kg. Their fur is warm brown above and creamy white on the face, chest, and inner limbs. Dark, expressive eyes scan for danger while nimble fingers probe bark crevices for insects. Troops of up to twenty individuals move through the canopy, led by experienced females who choose the day’s path. At dawn, males bark in chorus, warning rivals and claiming feeding rights. These capuchins are quick learners, using sticks to dig for insects and stones to crack open nuts. They are deeply social, grooming each other and forming strong family bonds.

Threats

The Ecuardorian White-fronted Capuchin is affected by deforestation and hunting for bushmeat and the pet trade. Forests in the western lowlands of Ecuador have been severely reduced in the past half-century (Dodson and Gentry 1991, Sierra 2013, Gonzalez-Jaramillo 2016). Where habitat loss has fragmented forests, Cebus aequatorialis forages in plantations of corn (maize), bananas, plantain and cacao, and is persecuted and hunted by farmers for this reason.

IUCN red list

Palm oil, timber, meat, and soy deforestation

The Ecuadorian White-fronted Capuchin is classified as Critically Endangered due to catastrophic habitat loss, with over 90% of their original forest destroyed since the 1970s. Palm oil plantations, cattle ranching, and soy fields have replaced ancient trees and dense canopies with monocultures that offer no food or shelter. Logging companies and ranchers burn the understory, while new roads slice through the last forest fragments, leaving capuchins trapped in shrinking islands.

Hunting, bushmeat, and illegal pet trade

When the forest is destroyed this exposes the capuchins to predatory birds, domestic dogs, and hunters. Farmers shoot Ecuadorian White-fronted Capuchins when they raid crops. Hunters target adults for bushmeat and capture infants for sale in local markets and border towns. The pet trade is especially brutal: infants are torn from mothers, who are often killed. Most captured juveniles die from stress, dehydration, and malnutrition before sale. Removing even a few breeding females from a small population can collapse an entire troop. Weak enforcement and low penalties mean illegal hunting and trade continue, even in protected areas. The trauma of captivity and the loss of family bonds cause extreme suffering and early death for capuchins in the illegal pet trade (Cervera et al., 2018; Guerrero-Casado et al., 2020).

Hunting, bushmeat, and illegal pet tradeMining, pollution, and fire

Mining operations in Esmeraldas and Manabí dump toxic sediment and chemicals into rivers and streams, killing the aquatic insects and crabs capuchins need for protein. Open-pit mines destroy entire watersheds, leaving behind barren land where forest once stood. Mining roads allow illegal loggers and hunters deeper access, accelerating destruction. Fires set for pasture or mining often escape, burning fruit trees and destroying nesting sites. Pesticides and herbicides sprayed on crops poison insects and contaminate streams, further reducing food sources for capuchins. The cumulative impact of mining, fire, and pollution leaves the remaining habitat degraded and dangerous for the Ecuadorian White-fronted Capuchin (González-Jaramillo et al., 2016; Sierra, 2013).

Fragmentation and population collapse

Many forest fragments are now too small to support a troop year-round. Deforestation continues even inside protected areas, with satellite data showing ongoing annual losses. Isolated groups face genetic bottlenecks and inbreeding, further threatening survival (Dodson & Gentry, 1991; González-Jaramillo et al., 2016; Sierra, 2013).

Field surveys at 83 forest fragments found capuchins at only 13 sites, many with encounter rates below one animal per kilometre walked. Camera traps in Pacoche and Punta Gorda record fewer than two capuchins per thousand trap-days. The population is now so small and scattered that inbreeding, disease, and local extinction are constant risks. Suitable habitat in Peru is confined to just 611 km² inside two reserves, both threatened by illegal logging and fire. Even a small increase in adult deaths could push the species beyond recovery (Guerrero-Casado et al., 2020; Jack & Campos, 2012).

Diet

Ecuadorian White-fronted Capuchins are omnivores, feasting on figs, guavas, palm nuts, beetles, spiders, and small lizards. They dig into rotten logs and leaf litter with agile hands, and wade into streams to catch freshwater crabs. When wild fruit is scarce, they raid maize, banana, and cacao plantations, bringing them into conflict with farmers (Campos & Jack, 2013). Ecuadorian White-fronted Capuchins are the prey animals of large raptors, small cat carnivores such as margays and snakes.

Reproduction and Mating

Females give birth every two to three years after a gestation of about 160 days. A single infant clings to their mother’s back for five months and nurses for up to a year. Youngsters practise tool use and foraging skills by eight months, watched by older siblings and aunts. Males leave their birth troop at four to five years, while females often stay and form the core of the group. In undisturbed forest, capuchins can live for 25 years or more, but hunting and habitat stress cut most lives short (Campos & Jack, 2013).

Geographic Range

The Ecuadorian White-fronted Capuchin once ranged from the Guayllabamba–Esmeraldas river system in Ecuador south to Tumbes and Piura in Peru. Today, they survive in a handful of protected areas and private reserves: Cerro Blanco, Mache-Chindul, Chongón-Colonche, Jama-Coaque, Pacoche, and the Noroeste Biosphere Reserve. Their range has shrunk by more than 90%, and the remaining fragments are separated by farmland and pasture (Guerrero-Casado et al., 2020; Jack & Campos, 2012).

FAQs

How many Ecuadorian White-fronted Capuchins remain in the wild?

Population estimates suggest fewer than ten thousand Ecuadorian White-fronted Capuchins remain, with some sources placing the number below five thousand. Habitat suitability modelling once projected a carrying capacity of 12,500 individuals if all remaining forest fragments were occupied at median density, but field surveys show many of these areas are now empty. The population has declined by more than 80% over the last three generations, meeting IUCN criteria for Critically Endangered status. Camera trap studies in protected areas record encounter rates of less than one capuchin per 1,000 trap-days, indicating extremely low population densities (Campos & Jack, 2013; Cervera et al., 2018).

Why is the Ecuadorian White-fronted Capuchin classed as Critically Endangered?

The Ecuadorian White-fronted Capuchin has lost over 90% of their original forest habitat to palm oil, cattle, and soy. Ongoing hunting and the illegal pet trade further reduce numbers. Even inside reserves, illegal logging, mining, and fires persist, preventing population recovery. The combination of these threats meets the Red List criteria for Critically Endangered. The species is at risk of extinction within a generation unless urgent action is taken (Dodson & Gentry, 1991; Sierra, 2013).

Do Ecuadorian White-fronted Capuchins make good pets?

No. Captive capuchins develop bone disease, dental problems, and severe stress. The pet trade drives hunters to kill mothers and seize infants, accelerating extinction. Keeping these monkeys as pets is illegal and causes immense suffering. The pet trade is immensely cruel, rips families of monkeys apart and fuels extinction (Cervera et al., 2018).

Take Action!

Use your wallet as a weapon and #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife. Support indigenous-led conservation and agroecology. Adopt a #vegan lifestyle and #BoycottMeat to protect wild and farmed animals alike.

You can support this beautiful animal

There are no known conservation activities for this animal. Share out this post to social media and join the #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife on social media to raise awareness

Further Information

Donate to help orphaned capuchins at Merazonia

Campos, F. A., & Jack, K. M. (2013). A potential distribution model and conservation plan for the critically endangered Ecuadorian capuchin, Cebus albifrons aequatorialis. International Journal of Primatology, 34(5), 899–916. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-013-9704-x

Guerrero-Casado, J., Vega Guarderas, Z., & Cabrera, J. (2020). New records of the critically endangered Ecuadorian white-fronted capuchin (Cebus aequatorialis) in western Ecuador. Neotropical Primates, 26(1), 1–5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31915955/

Jack, K. M., & Campos, F. A. (2012). Distribution, abundance, and spatial ecology of the critically endangered Ecuadorian capuchin (Cebus albifrons aequatorialis). Tropical Conservation Science, 5(2), 173–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/194008291200500207

Moscoso, P., de la Torre, S., Cornejo, F.M., Mittermeier, R.A., Lynch, J.W. & Heymann, E.W. 2021. Cebus aequatorialis (amended version of 2020 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: e.T4081A191702052. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T4081A191702052.en. Downloaded on 06 June 2021.

Sierra, R. (2013). Patrones y factores de deforestación en el Ecuador continental, 1990–2010: Y un acercamiento a los próximos 10 años. Conservación Internacional Ecuador and Forest Trends. https://www.forest-trends.org/publications/patrones-y-factores-de-deforestacion-en-el-ecuador-continental-1990-2010/

New investigation in the Amazon documents impact of palm oil plantations on Indigenous communities – Mongabay Newscast

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Discover more from Palm Oil Detectives

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

2 thoughts on “Ecuadorian White-fronted Capuchin Cebus aequatorialis”