Doria’s Tree Kangaroo Dendrolagus dorianus

Location: Papua New Guinea (Central and Southeastern Highlands)

IUCN Status: Vulnerable

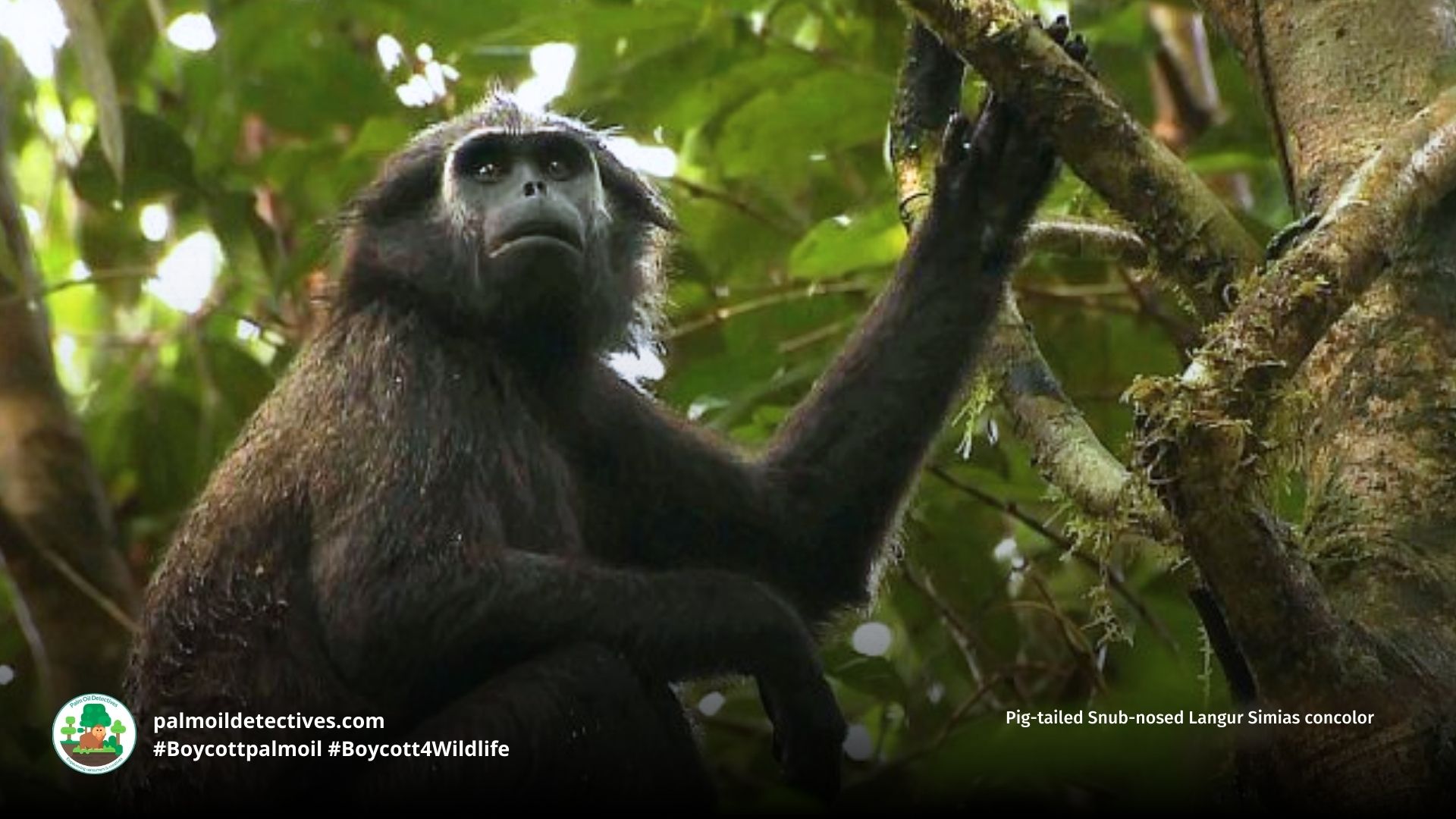

High in the misty mountain rainforests of Papua New Guinea, Doria’s Tree Kangaroo moves with deliberate agility through the dense canopy. With their thick brown fur, powerful limbs, and expressive dark eyes, these marsupials are a striking reminder of the ancient and unique wildlife of New Guinea. Unlike their terrestrial kangaroo cousins, Doria’s Tree Kangaroos have adapted to an arboreal life, leaping through tree canopies with ease and foraging among the leaves.

But their world is rapidly shrinking. Doria’s along with other tree kangaroos in the Dendrolagus genus are hunted mercilessly for bushmeat and threatened by palm oil deforestation, Gas mining and road infrastructure expansion, and land conversion, their numbers are in decline. Despite their elusiveness, they cannot escape the dangers encroaching on their rainforest home. Help them every time you shop and #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife

Doria’s Tree #Kangaroos 🦘🩷 are tree-dwelling #marsupials unique and endemic to #PapuaNewGuinea 🇵🇬 endangered by #palmoil 🌴 and #coffee ☕️ #deforestation #hunting 🔫 Support them when you #BoycottPalmOil 🌴🪔☠️🙊⛔️ #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2021/02/03/dorias-tree-kangaroo-dendrolagus-dorianus/

Appearance and Behaviour

Doria’s Tree Kangaroo is one of the largest of all tree kangaroo species, weighing between 6.5 to 14.5 kg and reaching up to 78 cm in body length, with a non-prehensile tail extending an additional 66 cm. Their thick, dense fur is a deep chocolate brown, with darker ears and lighter cream-coloured fur on their underside and tail. Their large, curved claws help them grip tree branches, giving them a bear-like appearance.

Despite their size, they are incredibly agile, able to leap between trees with precision. They are mostly solitary, with minimal interaction outside of mating and rearing young. In the wild, these agile tree kangaroos are crepuscular and nocturnal, foraging in the early morning and evening for food.

Geographic Range

Doria’s Tree Kangaroo is endemic to New Guinea, inhabiting montane rainforests between 600 and 3,650 metres in elevation. They are mainly found in southeastern Papua New Guinea, particularly in the Central and Eastern Highlands, Sandaun, and Chimbu Provinces.

These tree-dwelling kangaroos are most often seen in mossy primary forests, where the dense canopy provides cover from predators. However, their range is shrinking due to land clearing, road construction, and hunting pressure.

Diet

As a folivore, Doria’s Tree Kangaroo feeds on a variety of rainforest plants, including epiphytic ferns, leaves, buds, flowers, and fruits. They are particularly fond of Asplenium ferns, as well as native tree leaves and mosses.

Unlike terrestrial kangaroos, Doria’s Tree Kangaroos and others in the Dendrolagus genus do not graze on grass but instead rely on the rainforest understory, climbing to reach fresh foliage and descending when necessary.

Reproduction & Mating

Little is known about their exact reproductive cycle in the wild, but akin to other #marsupial mammals in the Dendrolagus genus, they are believed to breed year-round, with females giving birth to one joey per year. After a 30-day gestation period, the tiny, underdeveloped joey crawls into the mother’s pouch, where they remain for up to 10 months before venturing out.

Joeys become fully independent at around two years old, though they may stay close to their mother for some time.

Threats

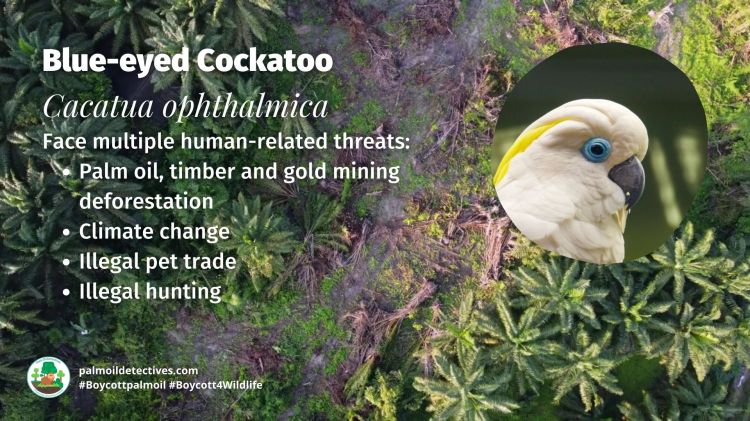

Doria’s Tree Kangaroo faces a barrage of threats, many of which are driven by human activity.

- #Hunting for #bushmeat: is the greatest threat to Doria’s Tree Kangaroo. These marsupials are heavily hunted using dogs, and as their numbers dwindle, they become even more vulnerable. Hunting is particularly intense in areas where traditional hunting practices continue unchecked. Local communities, particularly in Papua New Guinea, hunt these kangaroos using dogs, often for subsistence.

- Palm oil, coffee and timber deforestation: Habitat destruction for commercial agriculture, particularly coffee, palm oil, and subsistence farming, are fragmenting forests and forcing these tree kangaroos into smaller, isolated pockets.

- Infrastructure expansion: Deforestation for roads and and the expansion of liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects have decimated their range.

- Climate Change – As temperatures rise and weather patterns shift, high-altitude specialists like Doria’s Tree Kangaroo have nowhere left to go. Climate change is expected to alter the distribution of their food sources, further threatening their survival.

Without urgent conservation efforts, including the protection of their remaining habitat and an end to industrial deforestation, Doria’s Tree Kangaroo will continue its slow march toward extinction.

There are now logging concessions over almost 75% of the species inferred range. There has presumably been significant habitat disturbance and reduction in habitat quality as a result of logging

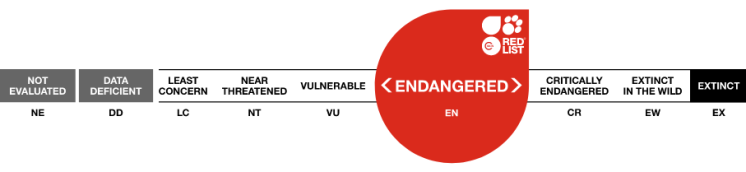

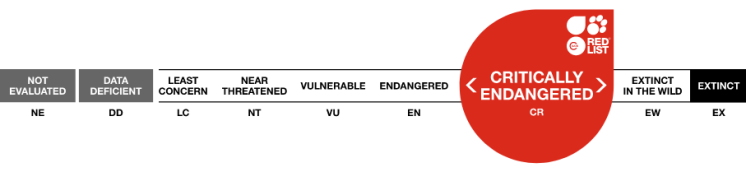

IUCN Red List

Take Action

Doria’s Tree Kangaroo is running out of time. Their home is vanishing under the relentless march of palm oil plantations, logging, and hunting. You can make a difference by refusing to buy products containing palm oil, supporting indigenous-led conservation efforts, and raising awareness of their plight. Every time you shop, choose 100% palm oil-free products to avoid contributing to deforestation and biodiversity loss. #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife

FAQs

How many Doria’s Tree Kangaroos are left in the wild?

There is no exact population estimate for Doria’s Tree Kangaroo, but researchers believe their numbers are declining rapidly due to hunting and habitat destruction. The species is classified as Vulnerable by the IUCN, meaning they are at significant risk of extinction if current threats continue (Leary et al., 2016). Tree kangaroos are difficult to study in the wild due to their remote habitat and elusive nature, but conservationists report that populations have become highly fragmented, with hunting pressure causing local extinctions in some areas. With increasing palm oil deforestation and infrastructure projects, their available habitat is shrinking, making long-term survival uncertain (Eldridge et al., 2018).

Are Doria’s Tree Kangaroos social animals?

Doria’s Tree Kangaroo is primarily solitary, interacting only during mating or when a mother is raising her joey. Unlike some tree kangaroo species, which form loose social groups, Doria’s Tree Kangaroo prefers to remain alone, moving quietly through the forest canopy. Studies on captive individuals suggest that tree kangaroos engage in social play when young, but adult interactions are limited (Martin, 2005). In the wild, they rely on their cryptic coloration and cautious movements to avoid predators and human hunters, making social interaction less practical for survival. However, mothers and joeys do maintain a strong bond, with joeys staying close to their mothers for up to two years before becoming fully independent (Flannery et al., 1996).

How do Doria’s Tree Kangaroos communicate?

Doria’s Tree Kangaroos use a variety of vocalisations, body language, and scent-marking to communicate. Researchers have documented at least six distinct vocal sounds, including soft chattering between mothers and joeys and deeper grunts or growls used to express alarm or territorial warnings (Eldridge et al., 2018). They also rely on scent-marking, rubbing their scent glands on tree trunks or branches to establish territories and signal their presence to others. These methods of communication are subtle compared to more social animals, but they play an essential role in navigating their environment and avoiding threats.

How high can Doria’s Tree Kangaroos jump?

Despite their large, stocky build, Doria’s Tree Kangaroos are remarkably agile, capable of leaping several metres between trees. Their powerful hind legs and sharp claws allow them to grip branches securely, while their strong, muscular forearms provide additional support when climbing (Martin, 2005). Unlike ground-dwelling kangaroos, which use their tail for balance when hopping, tree kangaroos rely more on their claws and limb strength to move through the canopy. They are also able to descend trees headfirst, a unique adaptation among macropods.

What are the main predators of Doria’s Tree Kangaroo?

Their primary predators include large pythons, raptors, and human hunters. While natural predators are a concern, humans pose the greatest threat, hunting tree kangaroos for bushmeat and using dogs to track them. As palm oil deforestation increases, tree kangaroos are forced into smaller patches of forest, making them easier targets for hunters. In some areas, habitat fragmentation has also made them more vulnerable to introduced predators such as feral dogs (Flannery, 1995).

What crops or types of agriculture are a threat to them?

Deforestation caused by palm oil, coffee plantations, and subsistence farming is a major threat to Doria’s Tree Kangaroo. These activities destroy their habitat, forcing them into isolated forest patches where food sources are scarce. Coffee and palm oil plantations, in particular, have expanded rapidly in Papua New Guinea, replacing large tracts of montane rainforest that these tree kangaroos rely on (Leary et al., 2016). The expansion of liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects and infrastructure development further compounds the issue, making it difficult for tree kangaroos to find suitable habitat.

You can support the conservation of this animal:

Further Information

Leary, T., Seri, L., Flannery, T., Wright, D., Hamilton, S., Helgen, K., Singadan, R., Menzies, J., Allison, A. & James, R. 2016. Dendrolagus dorianus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T6427A21957392. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T6427A21957392.en. Downloaded on 03 February 2021.

Tenkile Conservation Alliance. (2020). Tree Kangaroo Conservation in Papua New Guinea. Retrieved from https://tenkile.com/dorias-tree-kangaroo/

Valentine, P., Dabek, L., & Schwartz, K. R. (2021). What is a Tree Kangaroo? Evolutionary History, Adaptation to Life in the Trees, Taxonomy, Genetics, Biogeography, and Conservation Status. In Tree Kangaroos: Science and Conservation, Biodiversity of the World: Conservation from Genes to Landscapes (pp. 3-16). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-814675-0.00010-5

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Doria’s tree-kangaroo. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 13, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doria%27s_tree-kangaroo

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here