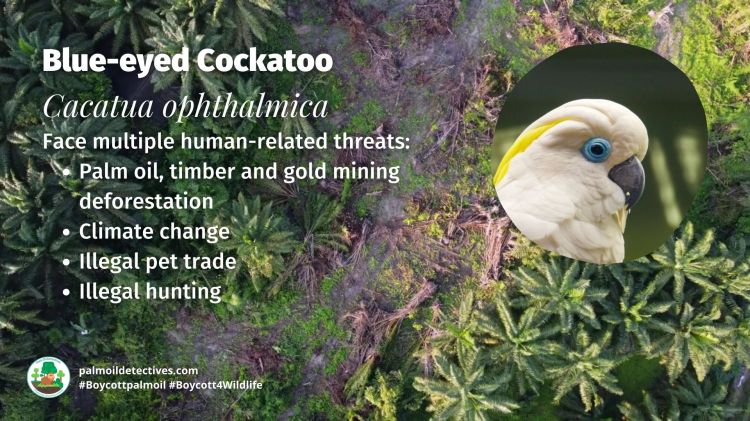

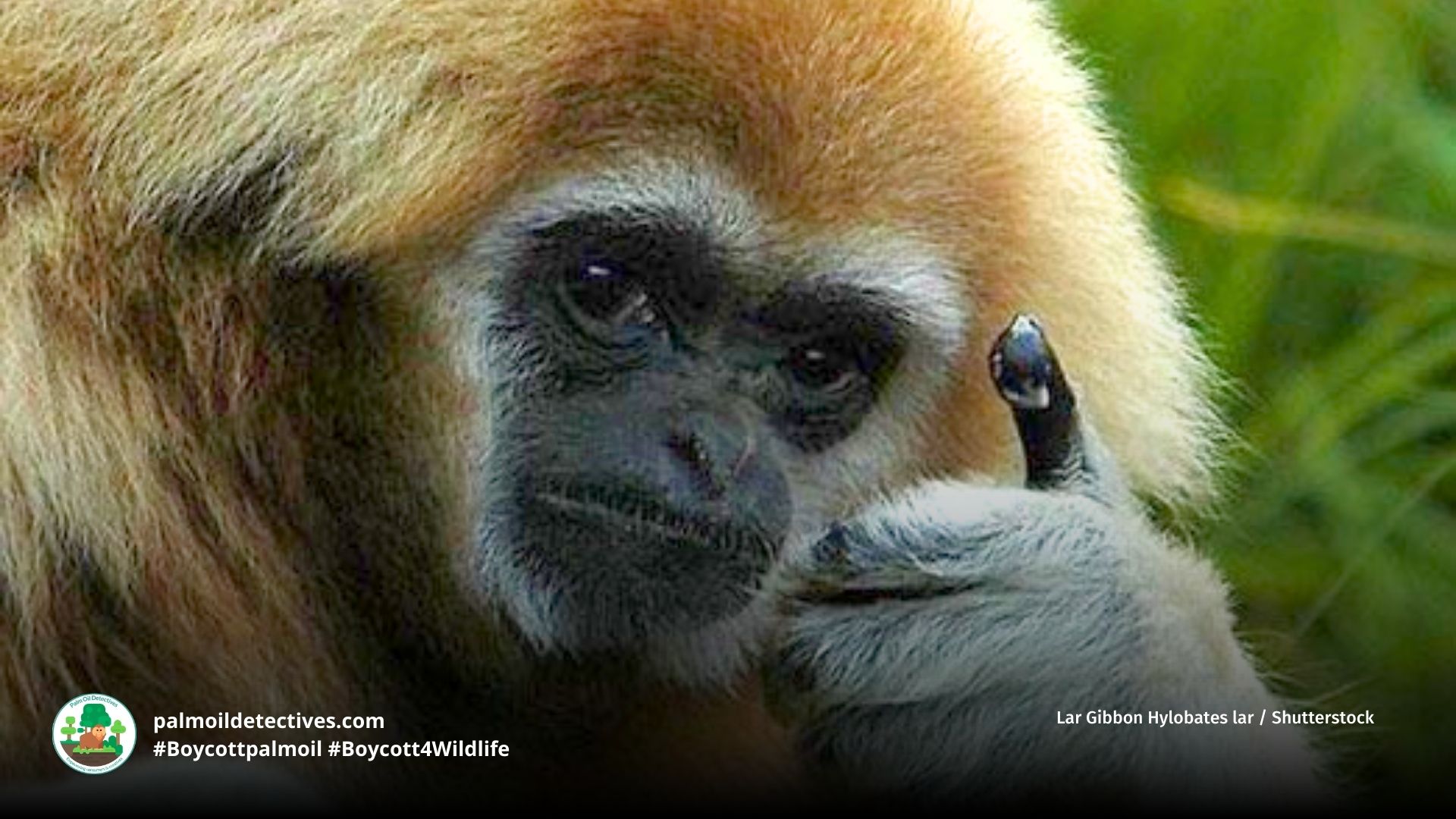

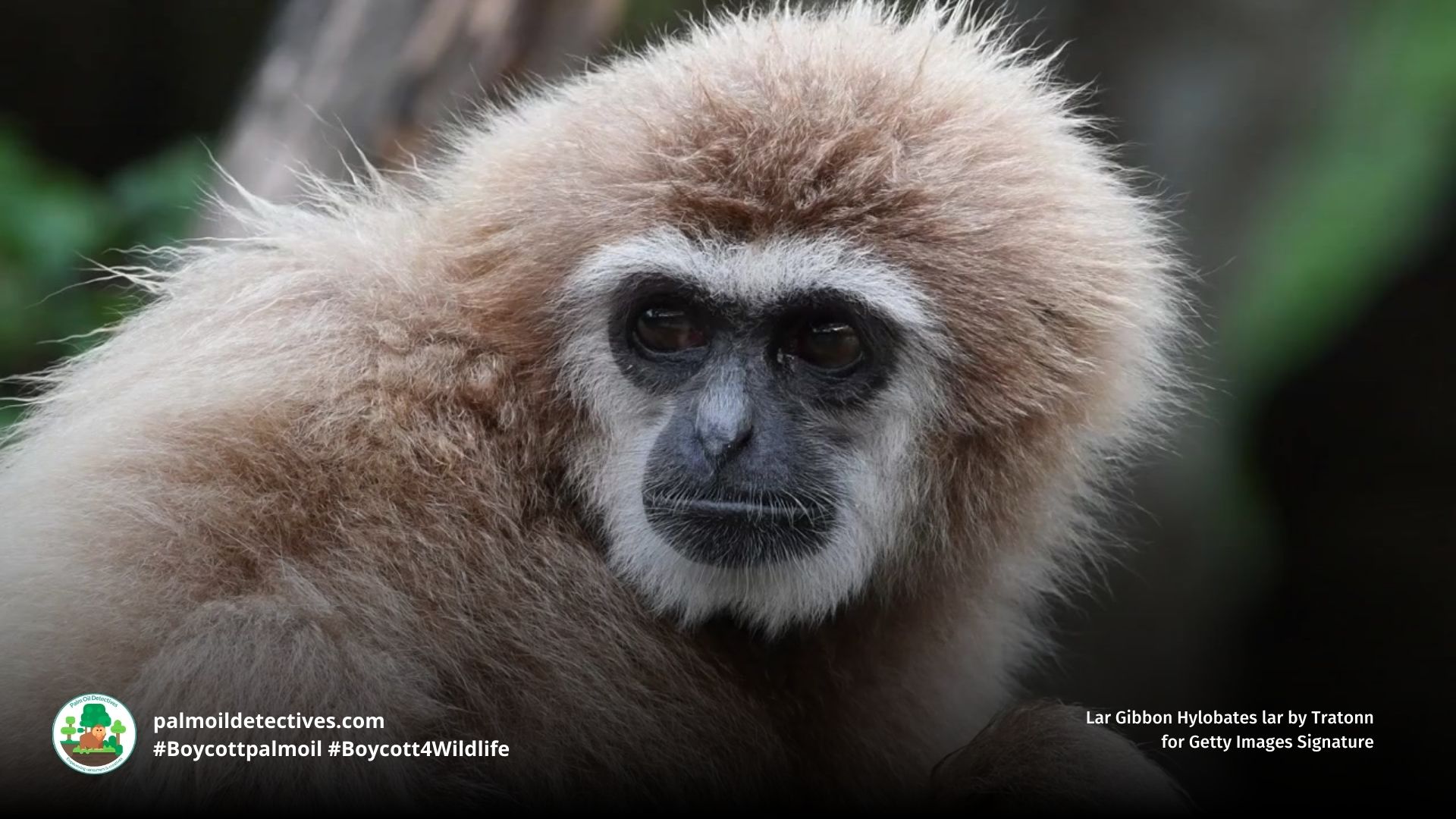

Lar Gibbon Hylobates lar

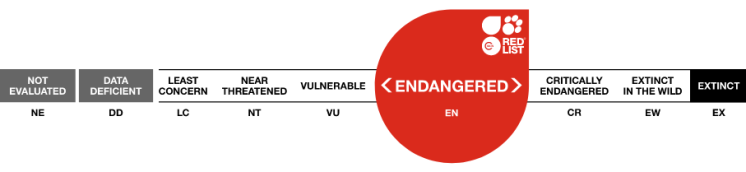

Endangered

Location: Found across the rainforests of Southeast Asia, including parts of Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Myanmar, and Laos.

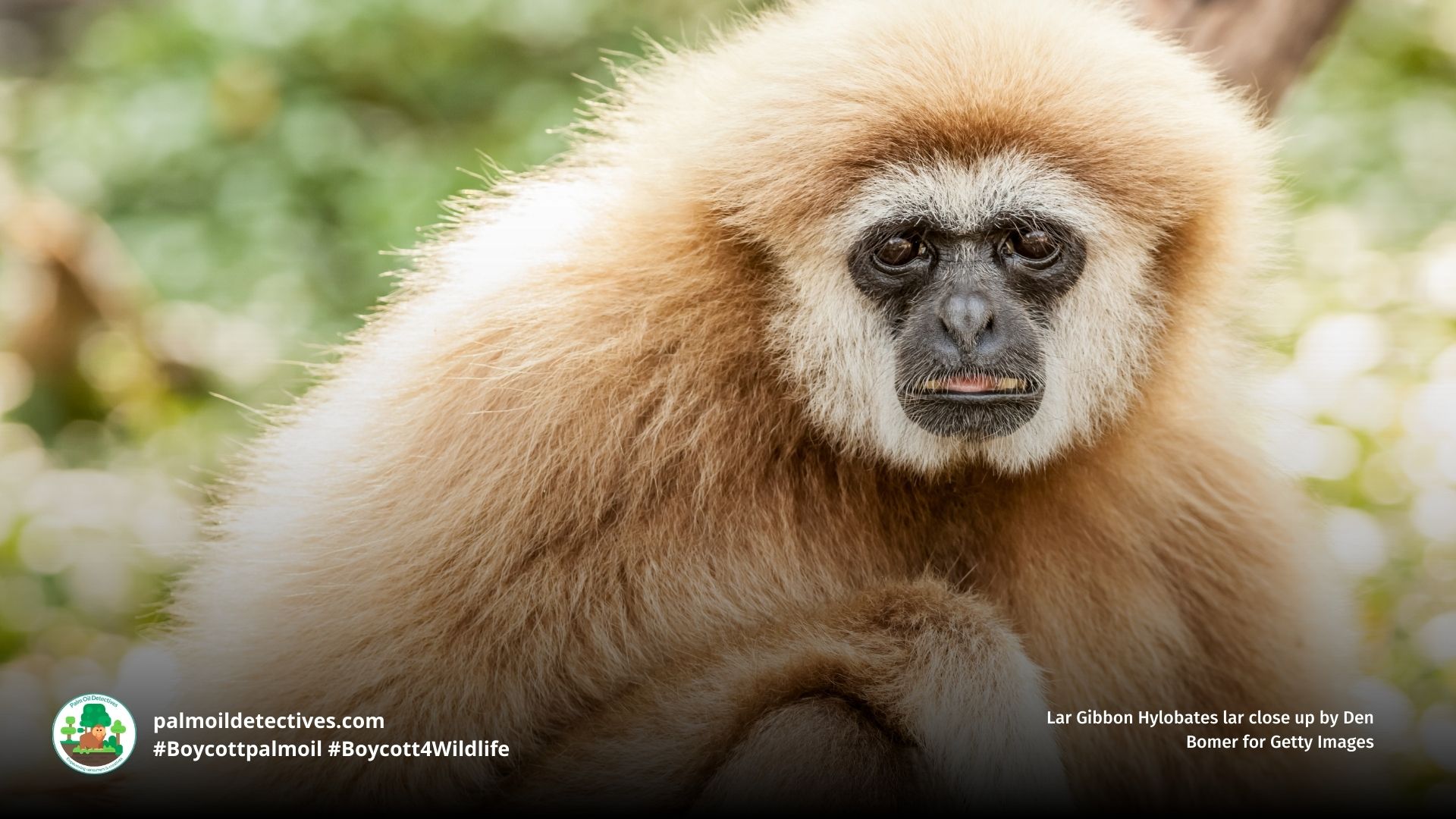

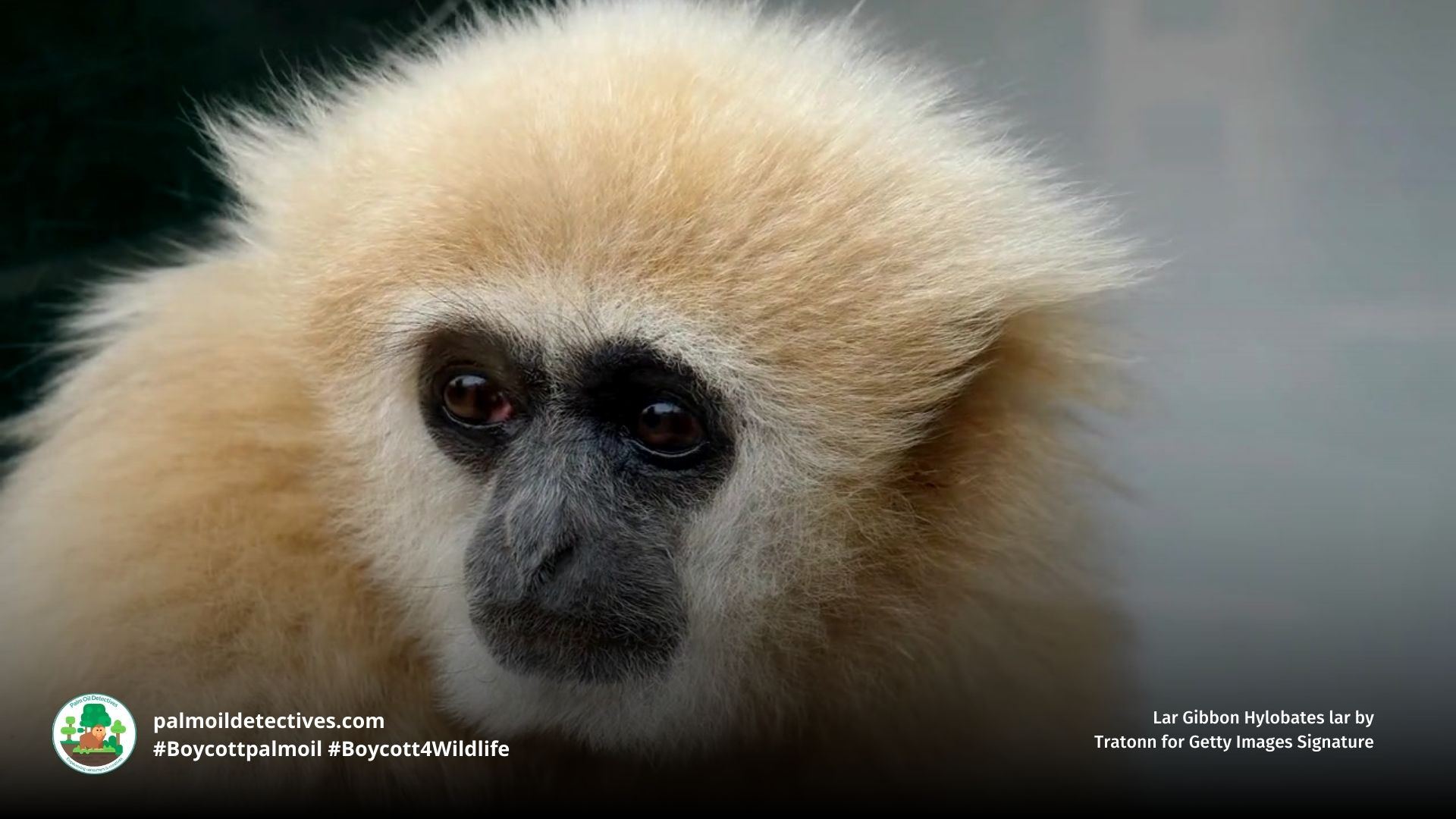

Gibbons, often called “lesser apes,” are no less than awesome! The Lar Gibbon Hylobates lar, also known as the white-handed gibbon, is a charismatic and acrobatic primate renowned for their incredible agility and melodic songs that echo through the rainforests of Southeast Asia. With their striking black or sandy-coloured fur and distinctive white markings on their hands and face, Lar Gibbons are both captivating and vital to their ecosystems.

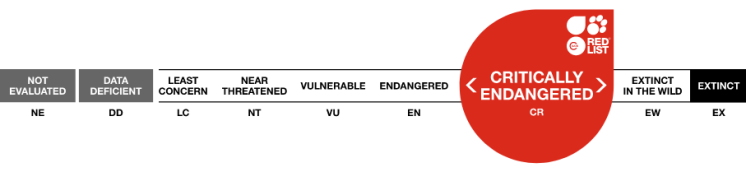

These gibbons are Endangered according to the IUCN Red List, facing rapid population declines due to habitat loss, poaching, and the illegal wildlife trade. Protecting these extraordinary primates means addressing deforestation, logging, and other threats head-on. Fight for their survival every time you shop. Use your wallet as a weapon, demand palm oil free and #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife.

The Lar Gibbon is one of the most outgoing and gregarious of the #gibbon species 🩷🤟🐵🐒 Endangered in SE #Asia from complex threats incl. #palmoil #deforestation, you can help them, every time you shop #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2021/02/05/lar-gibbon-hylobates-lar/

The true “party animals” of the jungle 🥳🪅🎉🐒🐵, Lar Gibbons are always up to something cheeky. They face serious threats from #palmoil #deforestation in South East Asia. Take action for them when you #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2021/02/05/lar-gibbon-hylobates-lar/

Ongoing localized forest loss due to shifting agriculture and commercial plantations of palm oil poses a threat.

IUCN Red List

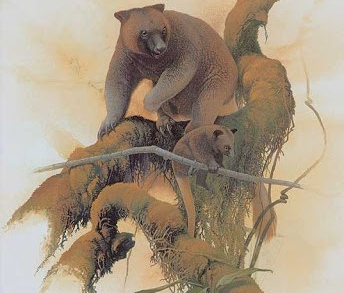

Appearance and Behaviour

Lar Gibbons are medium-sized primates, with adults weighing between 4–7 kilograms and measuring about 45–64 centimetres in height. They have dense fur ranging from black to sandy brown, with white fur encircling their faces and adorning their hands and feet. These markings give them their “white-handed” nickname.

Famous for their brachiation, Lar Gibbons swing effortlessly from branch to branch using their long arms, achieving speeds of up to 56 km/h and covering distances of up to 15 metres in a single leap. Their territorial calls are a hallmark of their behaviour, with males and females performing duet songs to communicate boundaries and strengthen pair bonds. These calls have been shown to exhibit structural complexity, akin to a form of primate “language” (Sci-News, 2015).

Threats

IUCN Status: Endangered

Habitat Loss for palm oil, timber and infrastructure:

Lar Gibbons face extensive habitat destruction due to logging, palm oil plantations, agriculture, and infrastructure development. Forest fragmentation isolates populations, making genetic exchange and survival more challenging (IUCN Red List, 2021).

Ongoing forest loss due to shifting agriculture and commercial plantations of palm oil poses a threat. On northern Sumatra, most of the lowland forests have been logged out and the threat of Ladia Galaskar, a network to link the west and east coasts of Aceh province, means that much of the remaining forest is at risk.

Poaching and illegal wildlife trade:

These gibbons are often hunted for bushmeat or captured for the exotic pet trade. Their charismatic nature makes them a target for illegal wildlife markets, with many young gibbons taken after hunters kill their mothers (Barelli et al., 2008).

Human-induced climate change:

Human-induced climate change is shifting rainfall patterns and rising temperatures. This is a threat to their rainforest habitats, further diminishing food sources and shelter for these gibbons.

Diet

Lar Gibbons are primarily frugivorous, feeding on a variety of fruits, supplemented by leaves, flowers, and insects. Their feeding habits play a crucial role in seed dispersal, contributing to forest regeneration. Seasonal variations in fruit availability influence their foraging behaviours and movement patterns.

Reproduction and Mating

Lar Gibbons are monogamous primates that form lifelong pair bonds. Breeding occurs year-round, with females giving birth to a single infant after a gestation period of about seven months. Young gibbons stay with their parents for up to eight years, learning essential survival skills before becoming independent.

Parental care is evenly shared, with both males and females playing active roles in protecting and teaching their offspring.

Geographic Range

The Lar Gibbon inhabits the rainforests of Southeast Asia, including Thailand, Myanmar, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Laos. They prefer dense, undisturbed primary forests but can sometimes be found in degraded habitats if food is available. However, their range is shrinking rapidly due to deforestation and habitat fragmentation.

FAQ

What are some interesting facts about the Lar Gibbon?

Lar Gibbons are masters of the treetops, using their long arms for brachiation, a form of swinging locomotion that allows them to travel efficiently through the forest canopy. They are one of the fastest arboreal mammals, capable of reaching speeds of 56 km/h. Their calls are not just territorial but have been likened to a form of “song” that contains unique structural patterns (Sci-News, 2015).

Why are Hylobates lar endangered species?

Lar Gibbons are endangered due to extensive habitat loss from logging, palm oil plantations, and agricultural expansion. Poaching for the illegal pet trade and hunting also significantly impact their populations. With forests disappearing at alarming rates, their survival depends on urgent conservation action (IUCN Red List, 2021).

Are Lar Gibbons aggressive?

Lar Gibbons are generally non-aggressive and shy towards humans. However, they can display territorial aggression within their own species. These confrontations are usually vocal and rarely involve physical altercations. Their vocalisations play a crucial role in asserting territorial boundaries (Barelli et al., 2008).

What are some facts about gibbons?

Gibbons, often called “lesser apes,” are no less than awesome! They are highly intelligent primates with complex social behaviours. They are known for their long arms and acrobatic abilities, allowing them to navigate forest canopies efficiently. Gibbons are unique among primates for their vocal duets, which are used to maintain pair bonds and communicate with neighbouring groups (PubMed, 2015).

Take Action!

The Lar Gibbon is a symbol of Southeast Asia’s fragile ecosystems, and their survival depends on the preservation of their rainforest homes. Join the fight against deforestation, support indigenous-led conservation, and boycott palm oil to protect their future. #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife

Support the conservation of this species

Numerous conservation efforts of these rarest of small primates are ongoing. Sponsor a gibbon at a rescue centre here.

Endangered Primate Rescue Centre

Further Information

Barelli, C., Boesch, C., Heistermann, M., & Reichard, U. H. (2008). Female white-handed gibbons (Hylobates lar) lead group movements and have priority of access to food resources. Behaviour, 145(5), 641–665.

Brockelman, W & Geissmann, T. 2020. Hylobates lar. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T10548A17967253. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T10548A17967253.en. Downloaded on 05 February 2021.

News Staff. (2015, April 10). Scientists decode ‘language’ of Lar Gibbons. Sci-News. Retrieved from https://www.sci.news/biology/science-language-lar-gibbons-02683.html

Terleph, T. A., Malaivijitnond, S., & Reichard, U. H. (2015). Lar gibbon (Hylobates lar) great call reveals individual caller identity. American Journal of Primatology, 77(7), 811–821. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.22406

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here