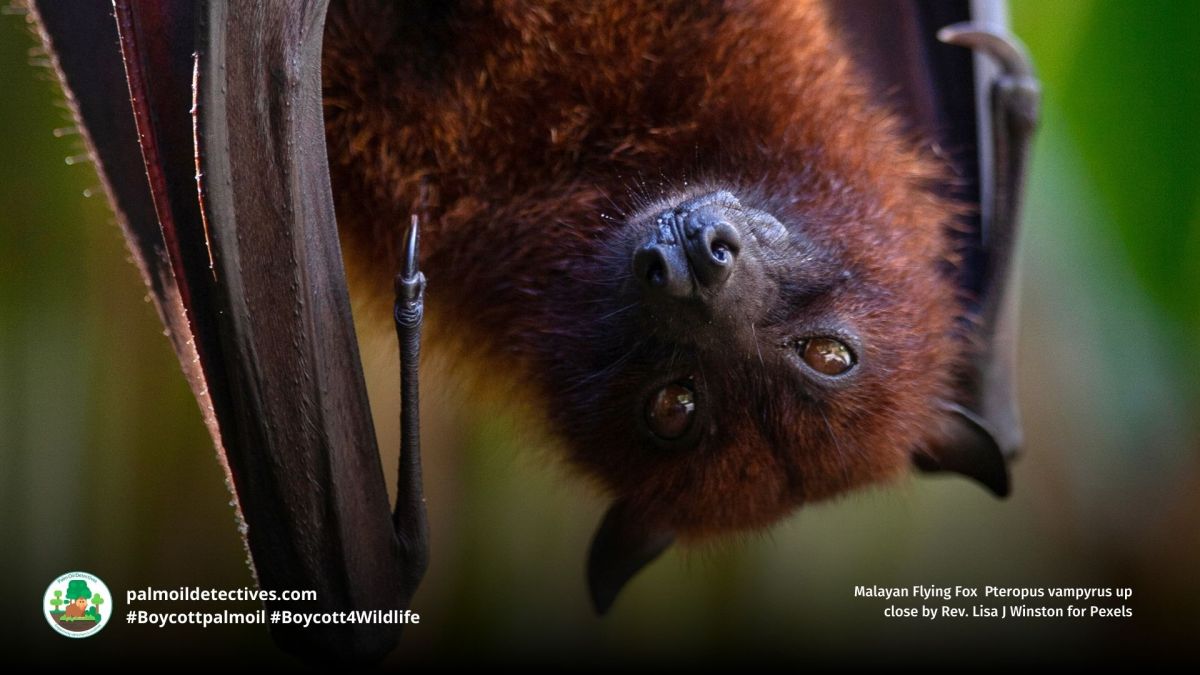

In an astonishing discovery, two marsupial species believed to be extinct for 6,000 years have been rediscovered alive and well in the remote rainforests of West Papua. The pygmy long-fingered possum and the ring-tailed glider were located with the crucial assistance of local indigenous Vogelkop clans. However, their survival remains precarious as their habitats are increasingly threatened by logging and the expansion of the palm oil colonialism in West Papua. Laws and native title to protect this region is essential for indigenous land defenders. We musn’t let them disappear again #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife

Two #extinct #marsupials in #WestPapua found alive! The #marsupials highlight the need to protect #Papuan forests or they are gone for good! Resist for them and #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife when you shop 🌴🙊🔥☠️🚫 @palmoildetect #Boycott4Wildlife https://wp.me/pcFhgU-iOH

Two #possums thought extinct for 6000 years are alive in #WestPapua! The pygmy #possum and sacred ring-tailed #glider deserve a break from #palmoil #ecocide. Stand with #indigenous defenders against #colonialism! 🌴🚫 @palmoildetect #BoycottPalmOil https://wp.me/pcFhgU-iOH

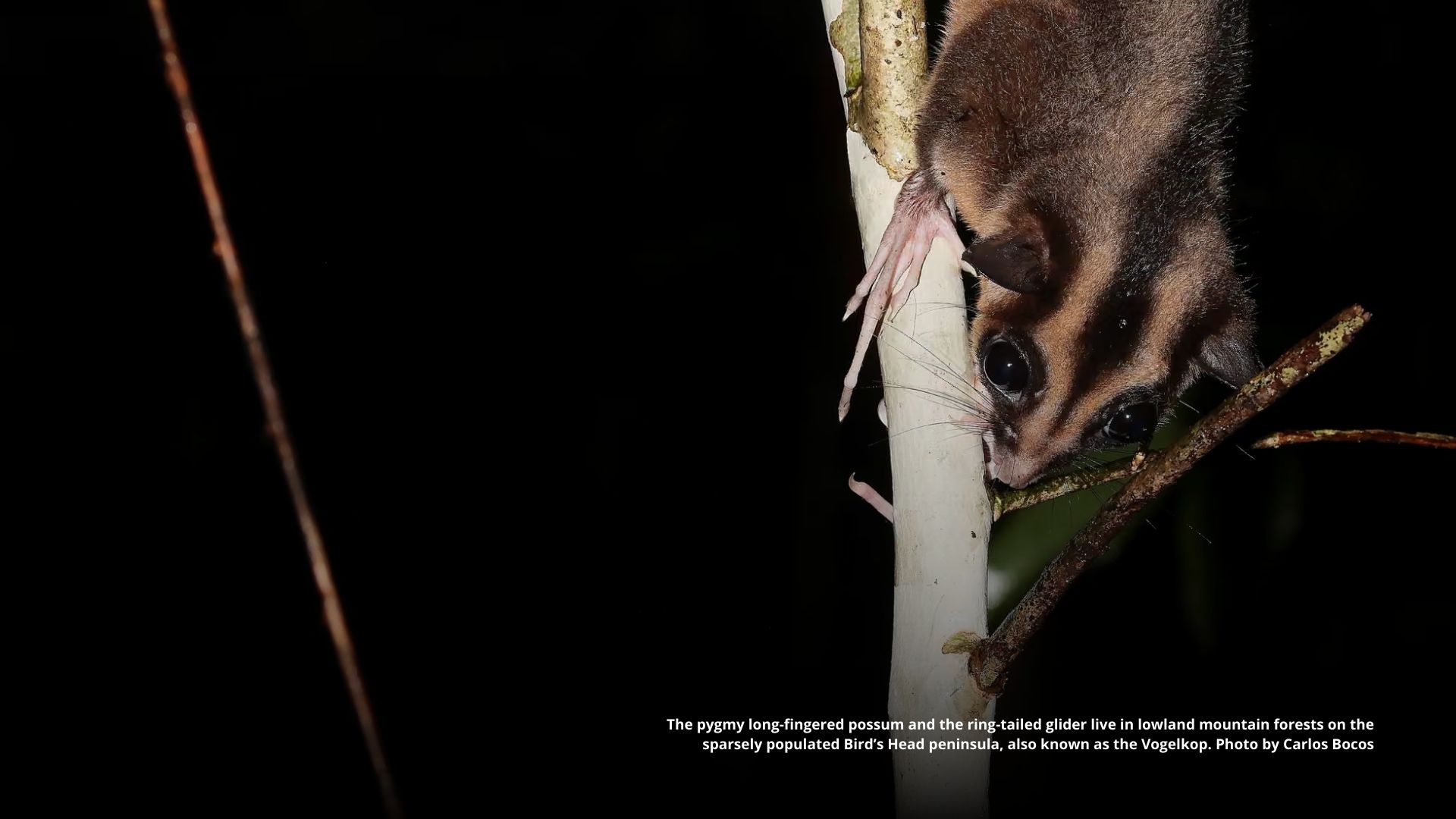

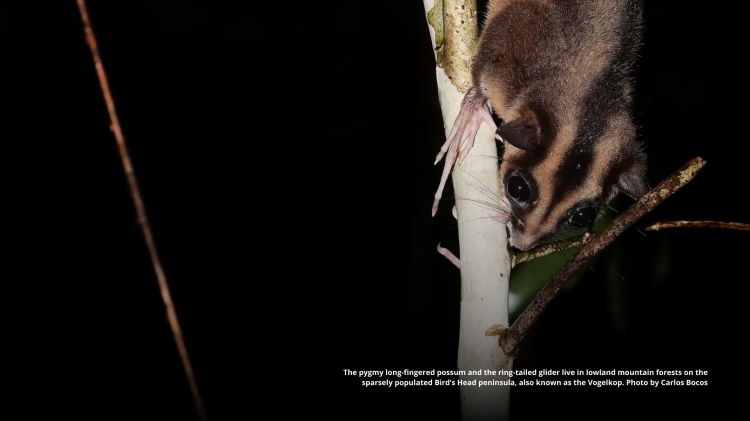

Two extraordinarily rare marsupials, entirely believed to have been extinct for over six thousand years, have been discovered alive in the remote, Vogelkop mountain forests of the Bird’s Head peninsula in West Papua. This remarkable rediscovery of the pygmy long-fingered possum and the ring-tailed glider was confirmed by Australian scientist Professor Tim Flannery, alongside a team of local indigenous experts and university researchers.

“More important than finding a living thylacine in Tasmania.”

Scott Hucknull from Central Queensland University describes the magnitude of the discovery.

These species are rare examples of “Lazarus taxa”. Animals who disappear from the fossil record only to be found alive centuries later. Flannery noted that the likelihood of finding even one lost mammal was almost zero, let alone two.

“It’s unprecedented and groundbreaking, really, to find two Lazarus taxa,” Flannery says. “We’ve been able to finalise two pieces of work that are incredibly important from a biological and a conservation perspective, documenting the existence of rare marsupials in an area under threat. It’s sort of a crowning glory in my career as a biologist.”

The first of the resurrected species is the pygmy long-fingered possum, Dactylonax kambuayai. This tiny, striped marsupial possesses an extraordinary evolutionary trait: an elongated fourth finger on each hand that is double the length of other digits. Flannery explains that they use this finger to extract grubs from timber.

“They’ve got a whole lot of specialisations in their ear region as well, which seem to be related to detection of low-frequency sound. So presumably they’re listening for wood-boring beetle larvae, and they then rip open the rotting wood and use that finger to fish out the grub,” Flannery says.

The second species, the ring-tailed glider (Tous ayamaruensis), features unfurred ears and a strong, prehensile tail used for gripping branches. Flannery calls it “one of the most photogenic animals, most beautiful marsupials you’ll ever see.”

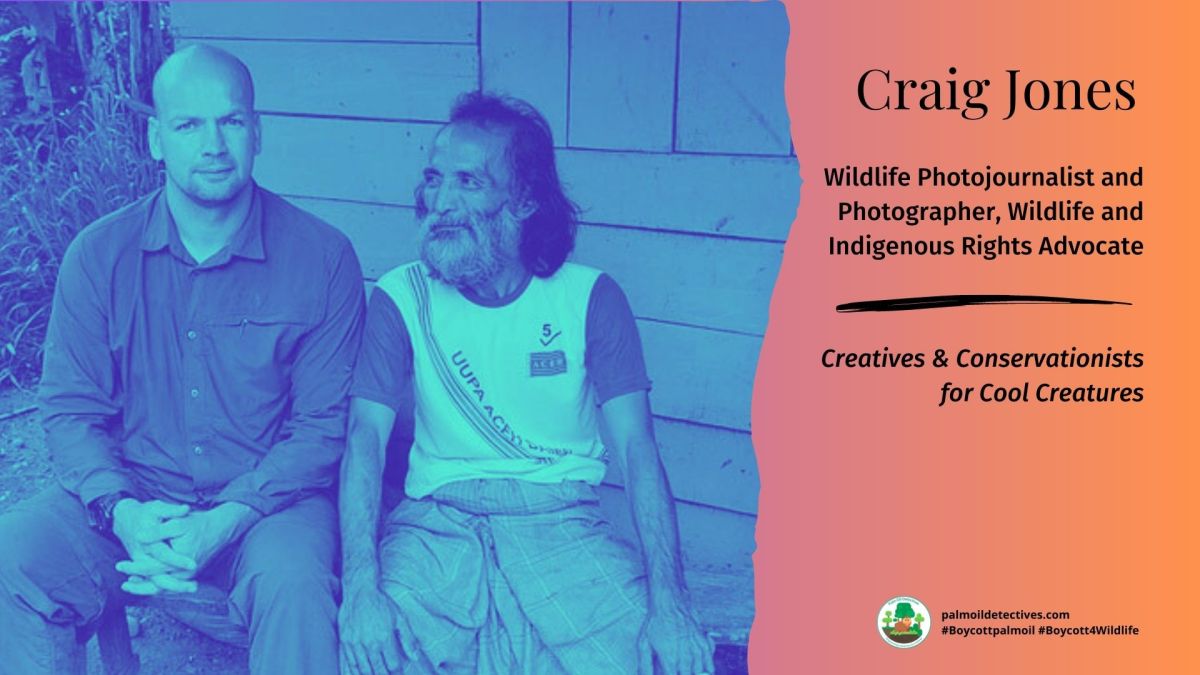

Crucially, the rediscovery of these elusive creatures was entirely dependent on the profound ecological knowledge of the local Tambrauw and Maybrat clans. These indigenous communities view the ring-tailed glider as deeply sacred, believing them to be manifestations of their ancestors’ spirits, and actively protect them from hunting. Rika Korain, a Maybrat woman and co-author of the research, emphasised that identifying the species relied entirely on traditional owners. “This connection has been essential,” she says.

“I’m very proud that Papuan researchers contributed to these landmark discoveries, and want to thank the people of the Misool, Maybrat and Tambrouw regions who supported us in the field,”

Dr Aksamina Yohanita of the University of Papua said.

“The Vogelkop is an ancient piece of the Australian continent that has become incorporated into the island of New Guinea. Its forests may shelter yet more hidden relics of a past Australia,”

Tim Flannery

To protect the remaining populations from the illegal wildlife trade, researchers are keeping their exact locations highly classified. Flannery delivered a stark warning to potential poachers regarding the animals’ survival in captivity: “They would be incredibly difficult to keep in captivity. because their diet is so highly specialised. Advanced warning for anyone who’s thinking of keeping one as a pet: it won’t live long,” he says.

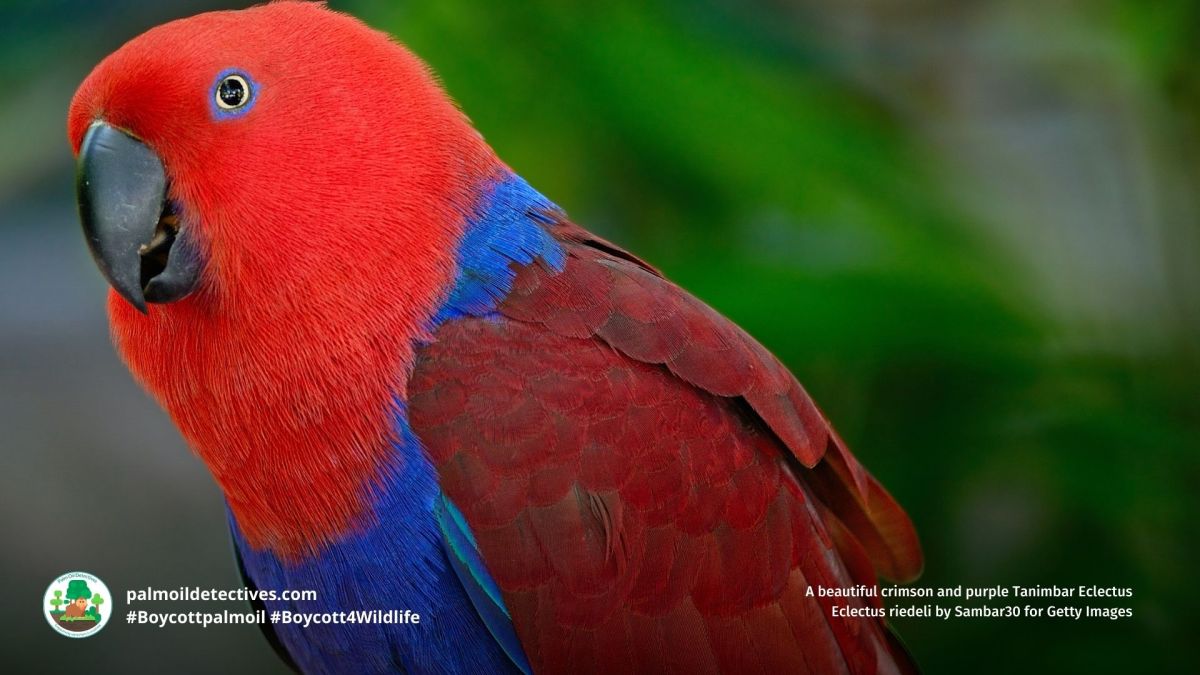

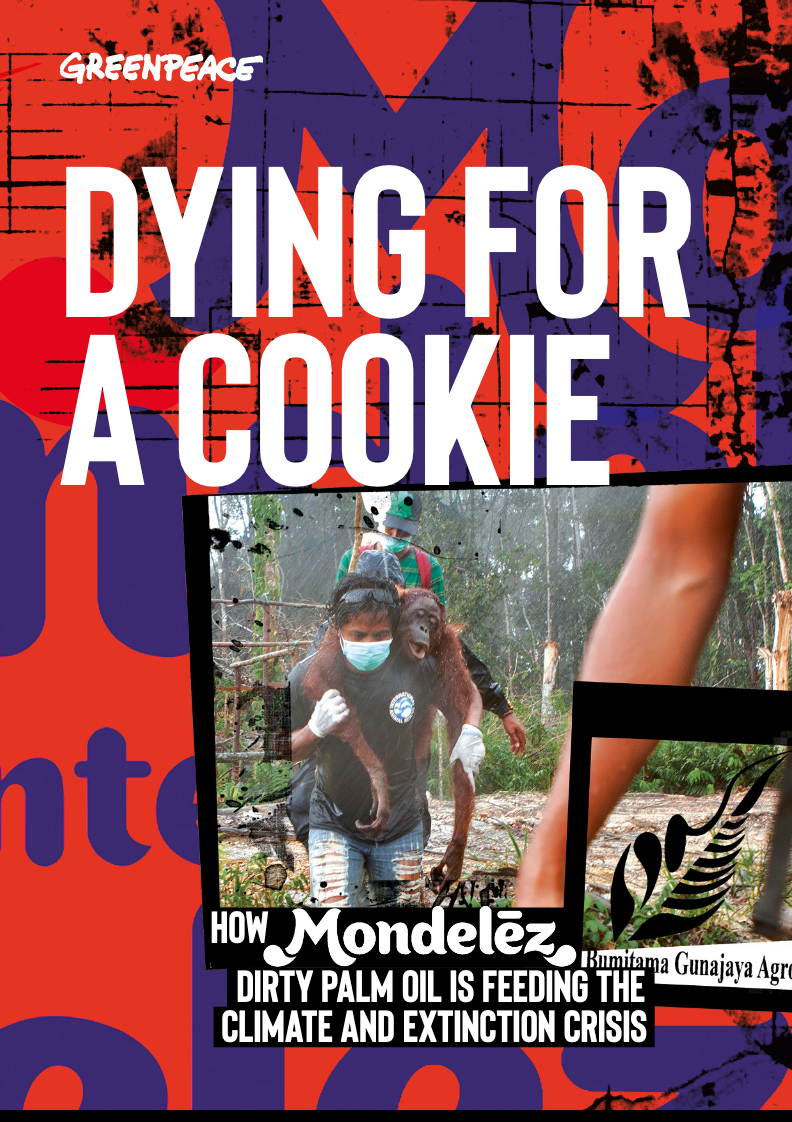

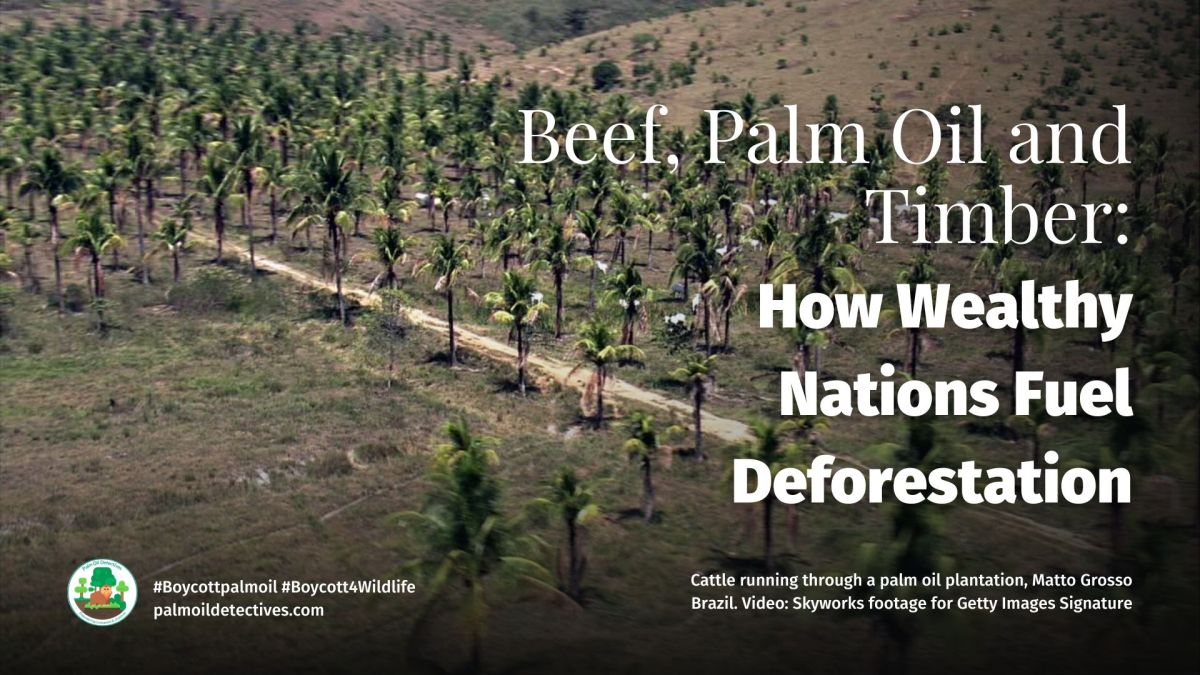

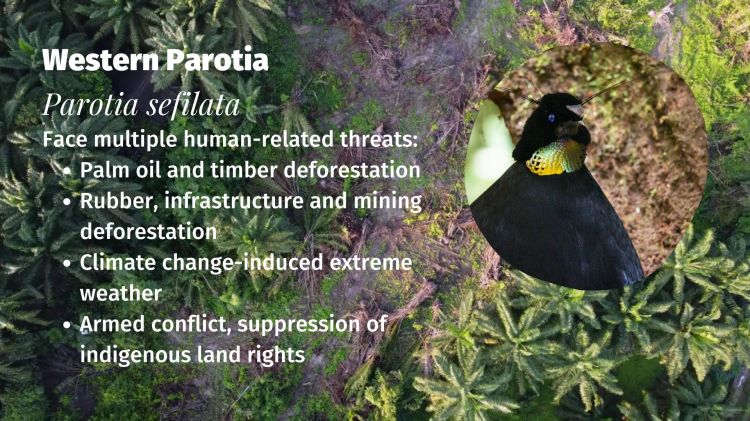

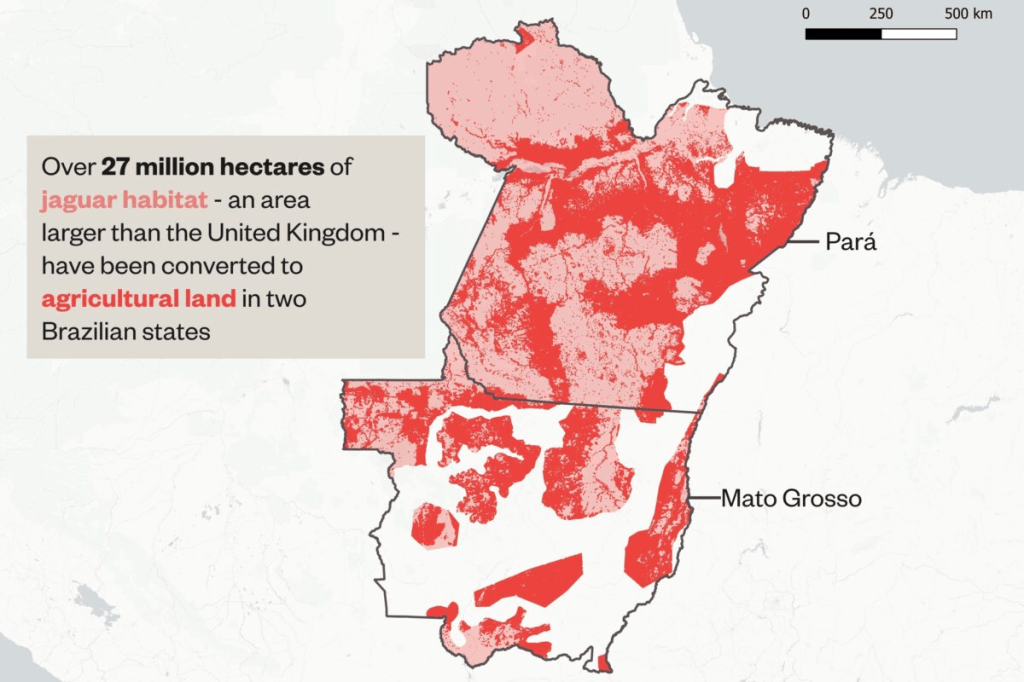

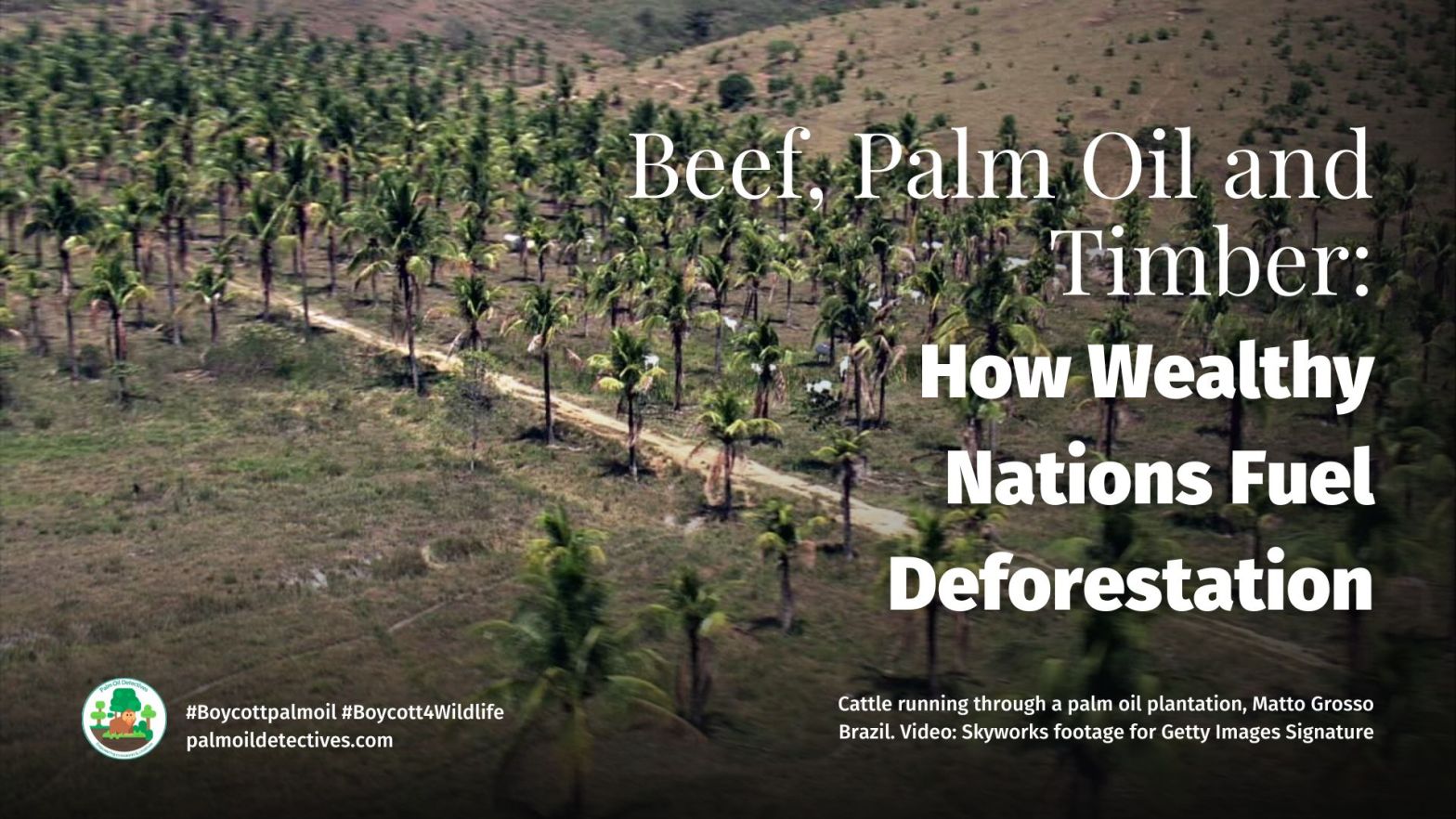

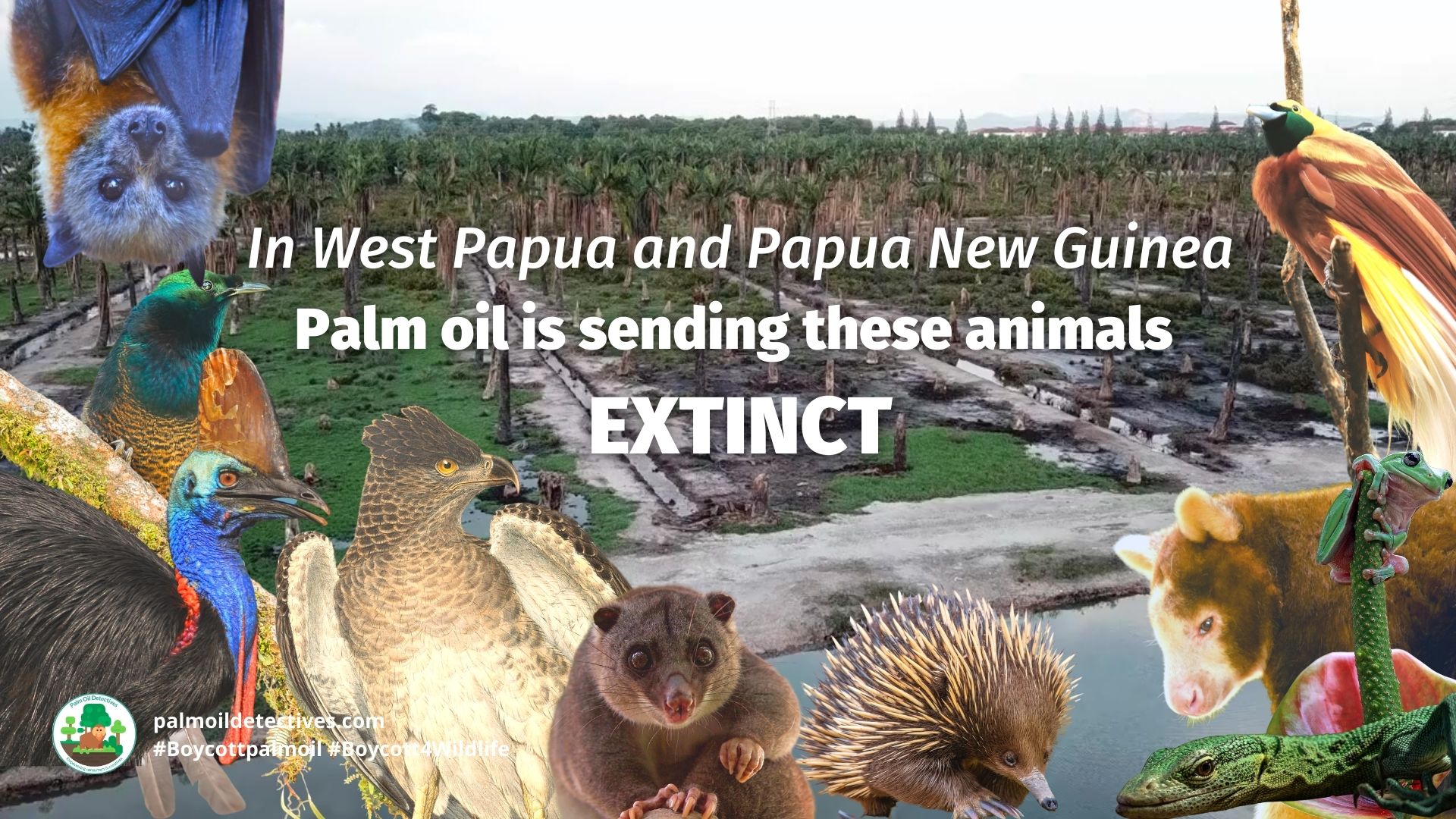

While their rediscovery is a triumph, their future is highly uncertain. The proximity of power-hungry corporates intent on razing the rainforest for palm oil and timber casts a dark shadow over the region.

David Lindenmayer, an ecologist at the Australian National University, who was not involved in the study said “I am also hugely concerned about the extent of logging and land clearing happening in New Guinea,” he says. “It also makes me wonder what might have been lost in Australia as a result of all of the land clearing that has taken place here.”

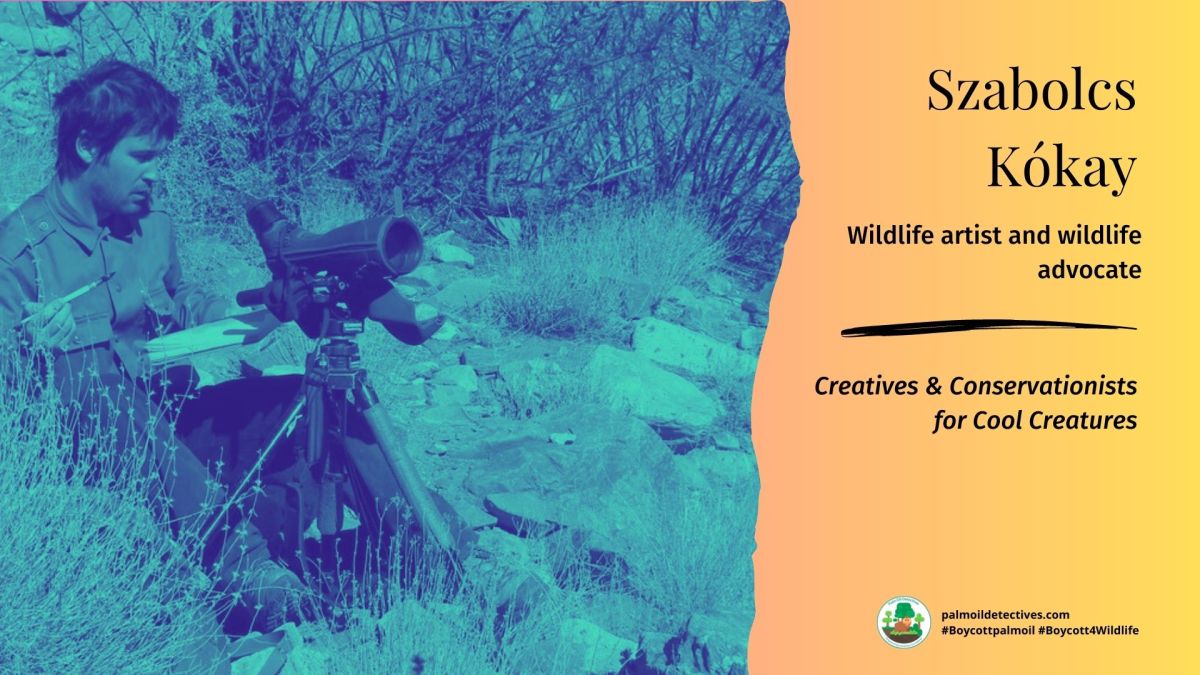

The findings underline strong calls from scientists, environmentalists and indigenous rights advocates for Native Title legal land rights and indigenous-led protections of West Papua and its imperilled Vogelkop rainforest where these delightful marsupials are found.

Further information

Lam, L. (2026, March 6). Tiny possum and glider thought extinct for 6,000 years found in remote West Papua. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cwyg6p8g6yjo

Morton, A. (2026, March 6). Marsupials previously thought extinct for millennia discovered in New Guinea. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2026/mar/05/marsupials-discovered-new-guinea

Woodford, J. (2026, March 5). Two marsupials believed extinct for 6000 years found alive. New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2518082-two-marsupials-believed-extinct-for-6000-years-found-alive/

ENDS

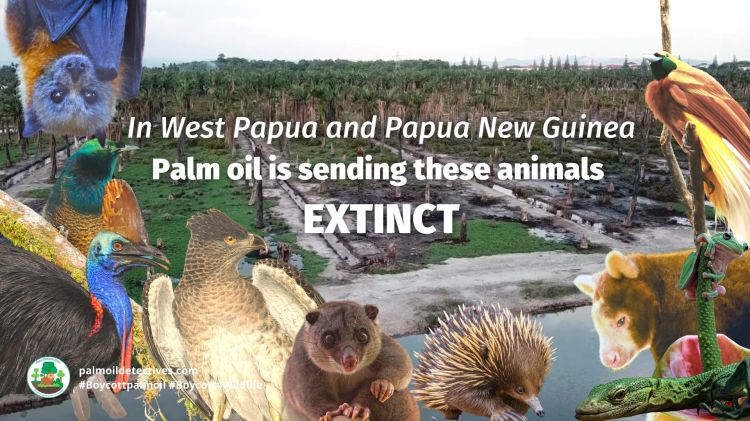

Learn about other animals endangered by palm oil and other agriculture

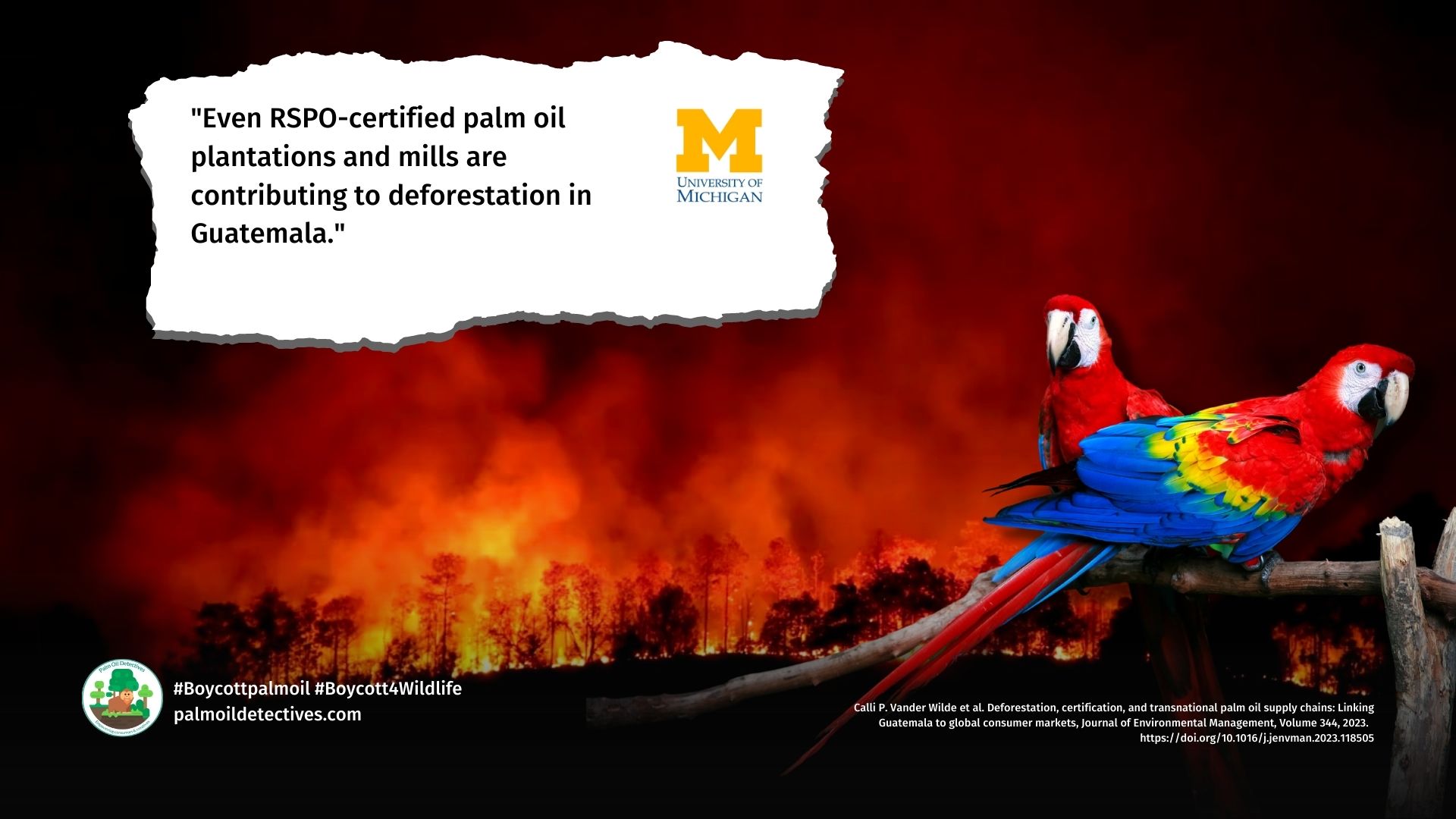

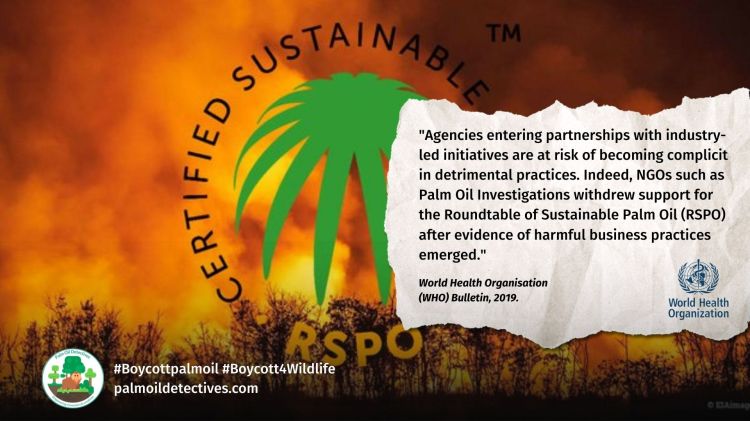

Learn about “sustainable” palm oil greenwashing

Read more about RSPO greenwashing

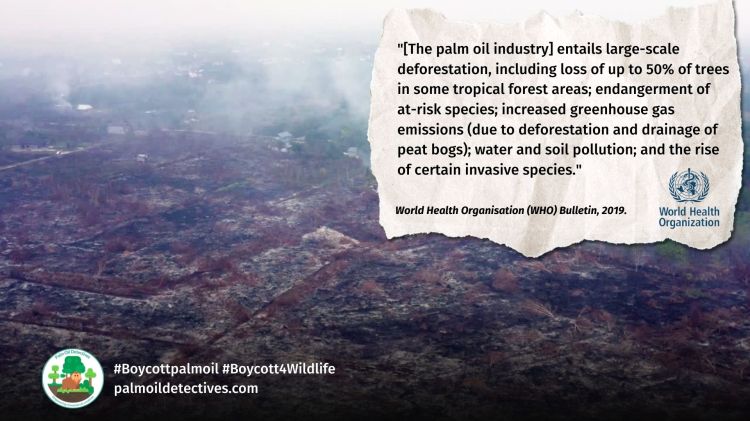

A 2019 World Health Organisation (WHO) report into the palm oil industry and RSPO finds extensive greenwashing of palm oil deforestation and the murder of endangered animals (i.e. biodiversity loss)

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here