Despite sustained and vigorous attempts by corporate FMCG giants and industry certification schemes like RSPO, MSC and FSC to downplay the impact and effectiveness of consumer boycotts, it turns out that boycotts are worthwhile and drive social change. They force profit-first and greedy corporations to change their ways and do better. Participating in boycotts creates a tangible sense of empowerment and agency for consumer-citizens who want to participate in civil society in a meaningful way. Ideal for those who want to unsettle the status quo to improve the world, both as individuals and in collective groups.

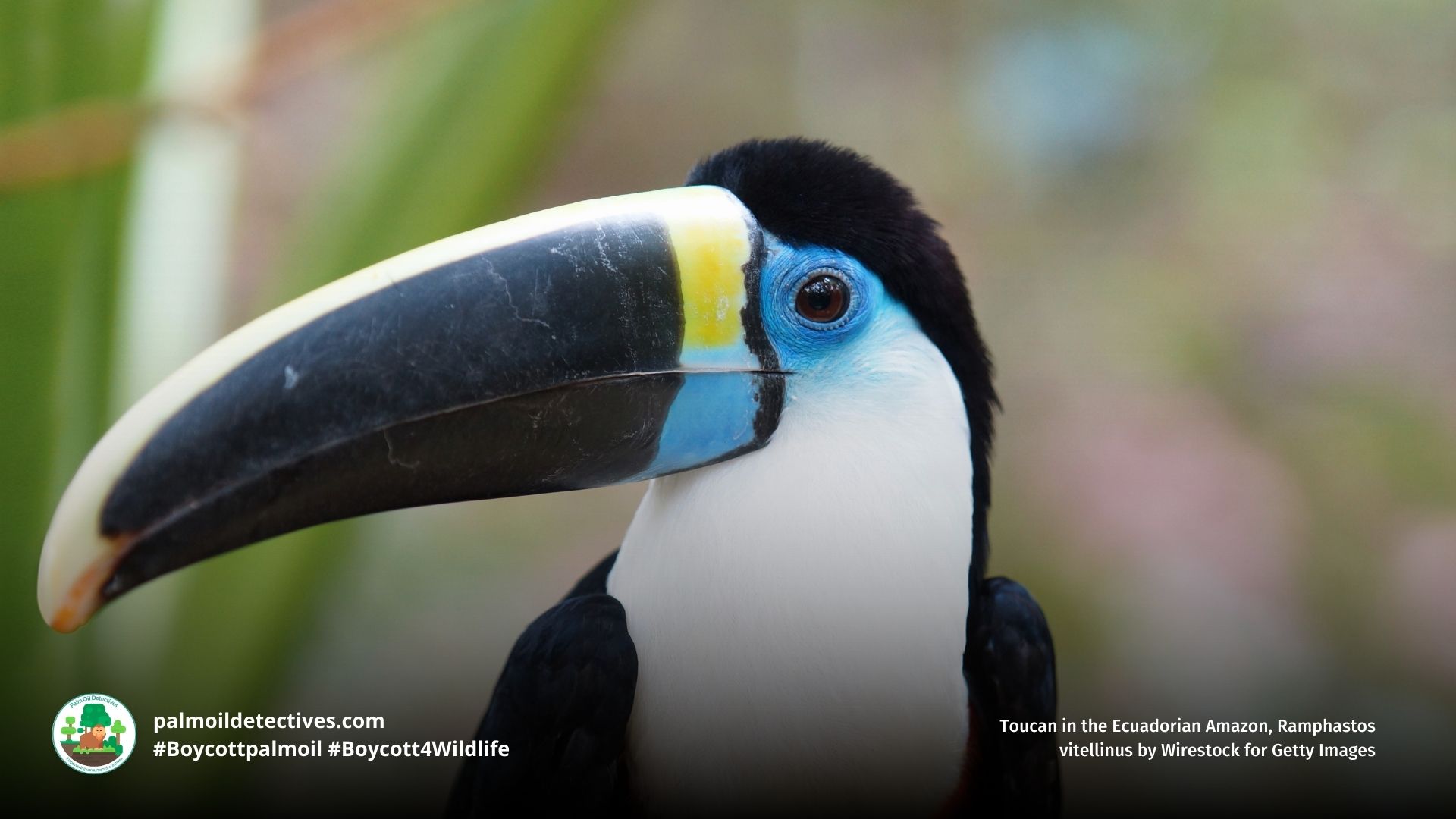

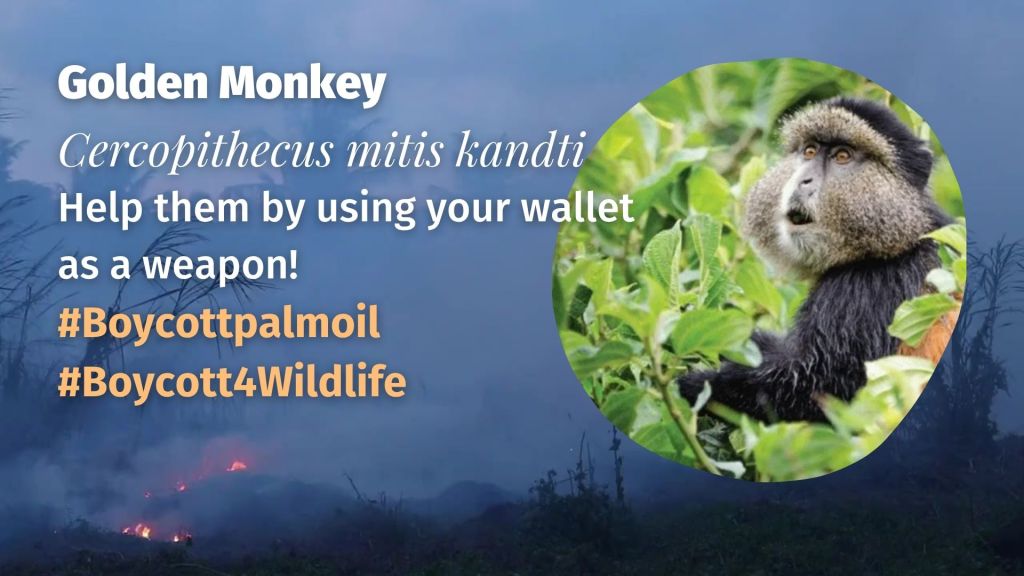

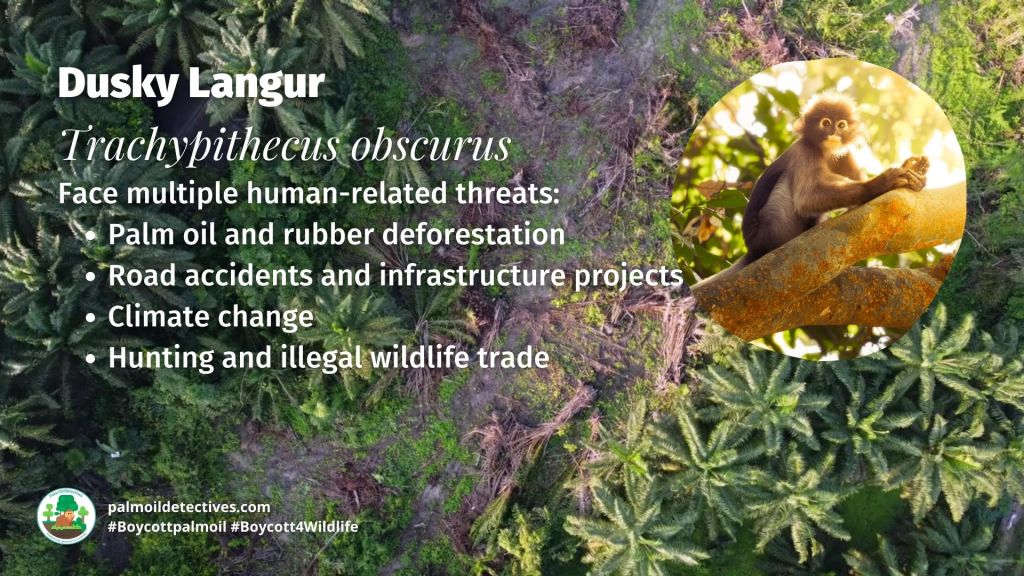

Consumer #boycotts are aggressively attacked by whole industries and #greenwashing #ecolabels like #RSPO as being ineffective. Yet a strong body of evidence shows they galvanise social change and empower citizens #BoycottPalmOil 🌴🚫 #Boycott4Wildlife https://wp.me/pcFhgU-2aA

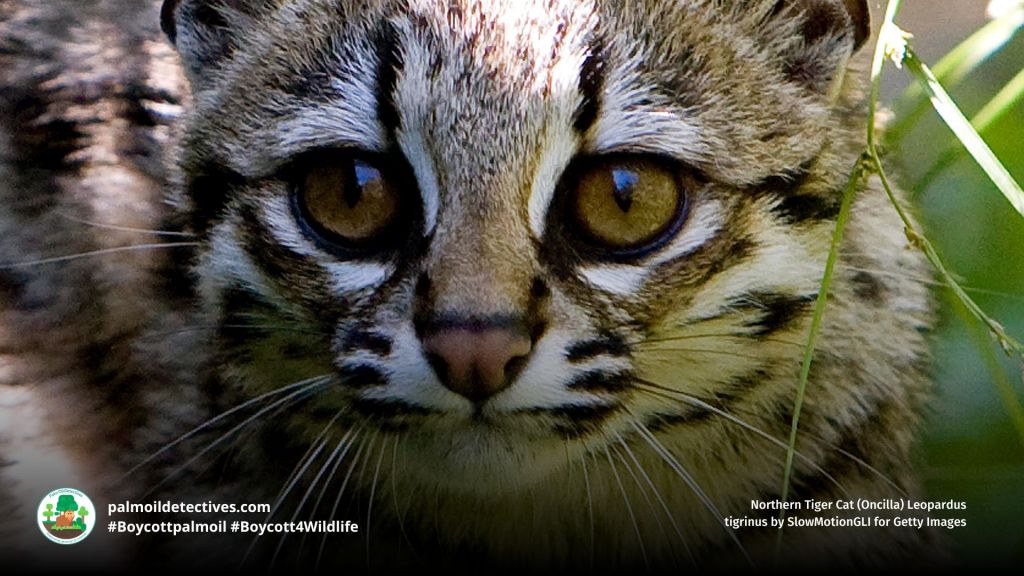

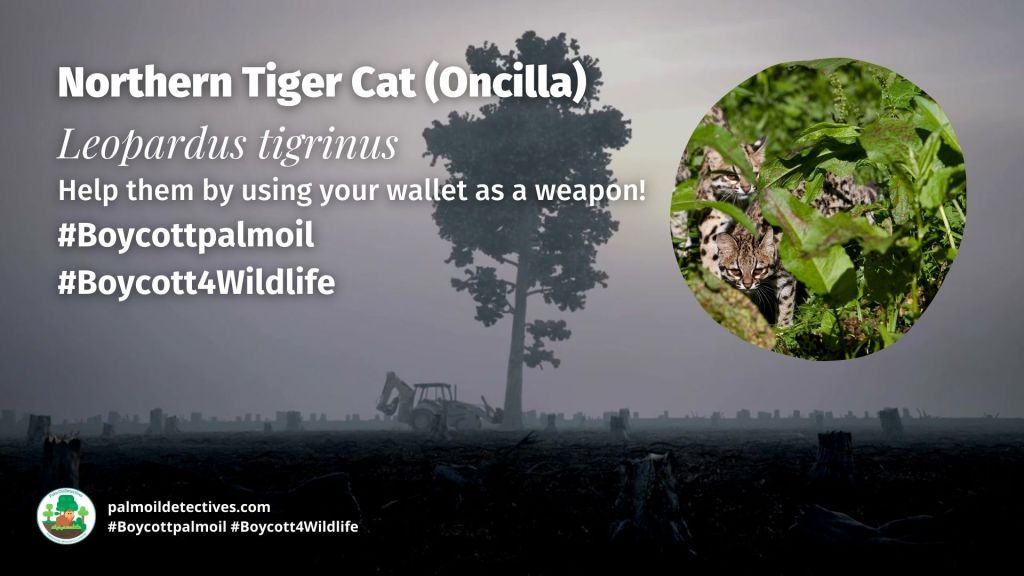

Cast as ‘rabble-rousers’ or ‘trouble-makers’, citizens who vote with their wallets and choose to #Boycott #palmoil and #meat are the vanguard protectors of our fragile future on earth! 🌿🫶 #Vegan #BoycottMeat #BoycottPalmOil🌴⛔️ #Boycott4Wildlife https://wp.me/pcFhgU-2aA

Over 4 years #Boycott4Wildlife’s 15,000+ advocates have consolidated their effectiveness on Twitter and altered the message on palm oil irrevocably during this time. In the process, the #Boycott4Wildlife global collective have educated people about the products they buy and the most environmentally damaging brands that hide behind the greenwashing veil “sustainable” palm oil.

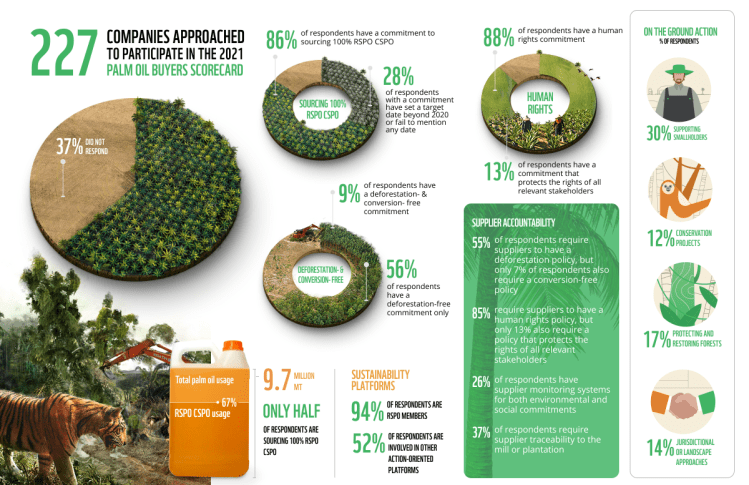

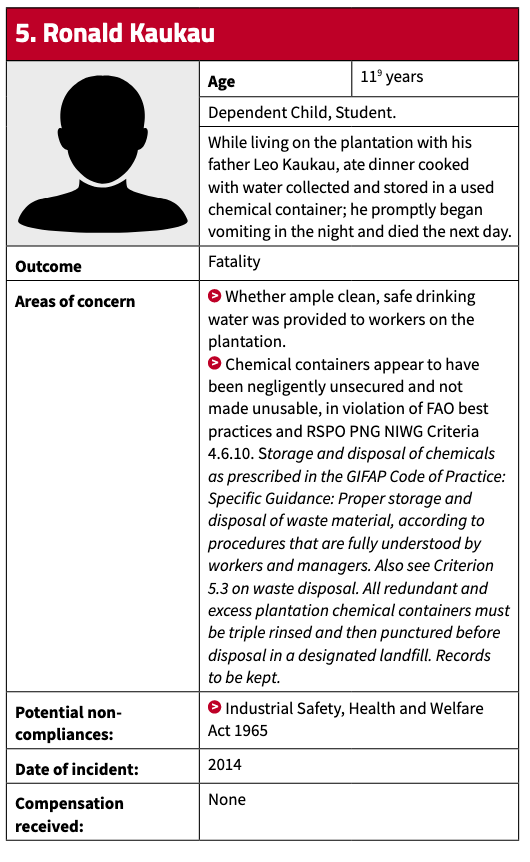

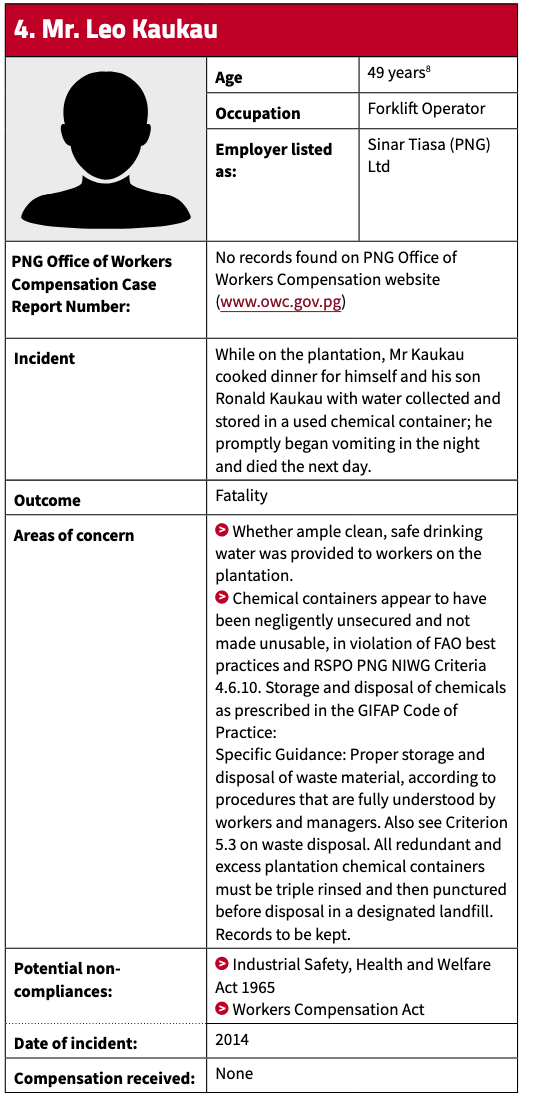

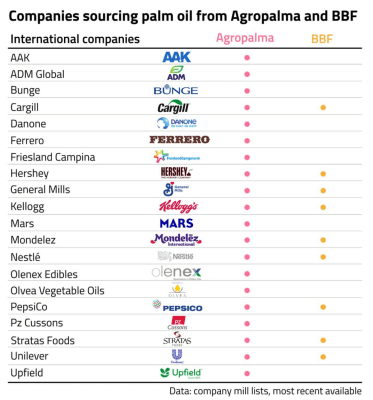

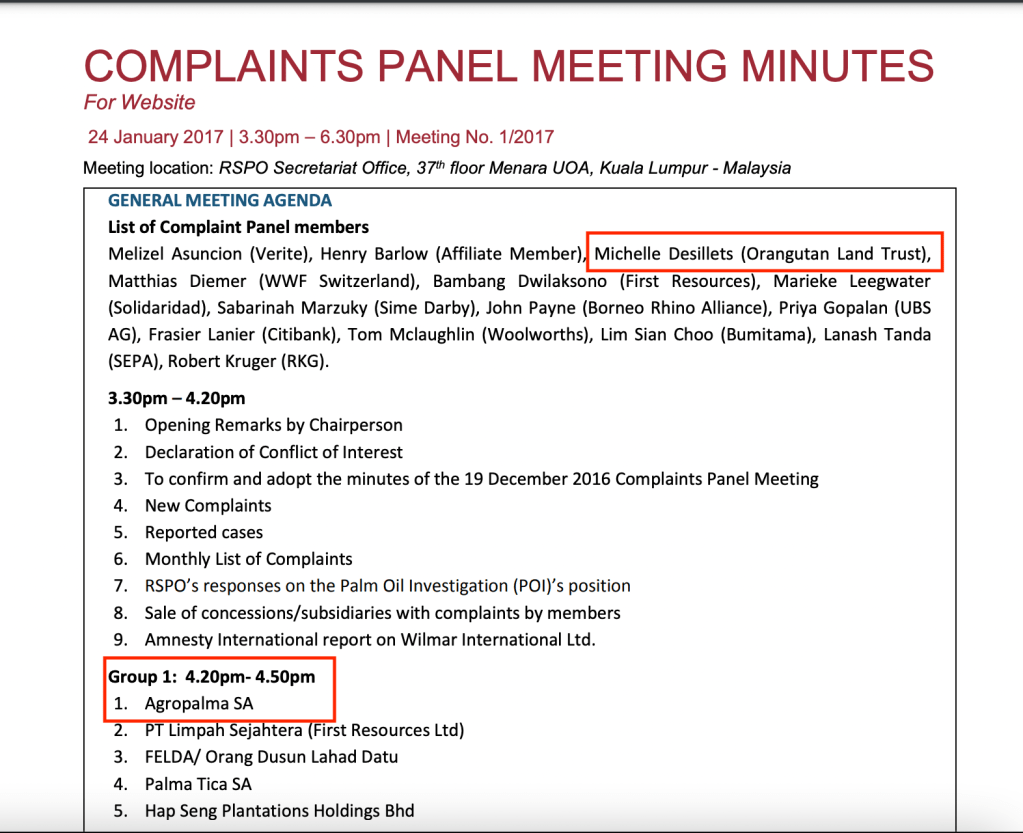

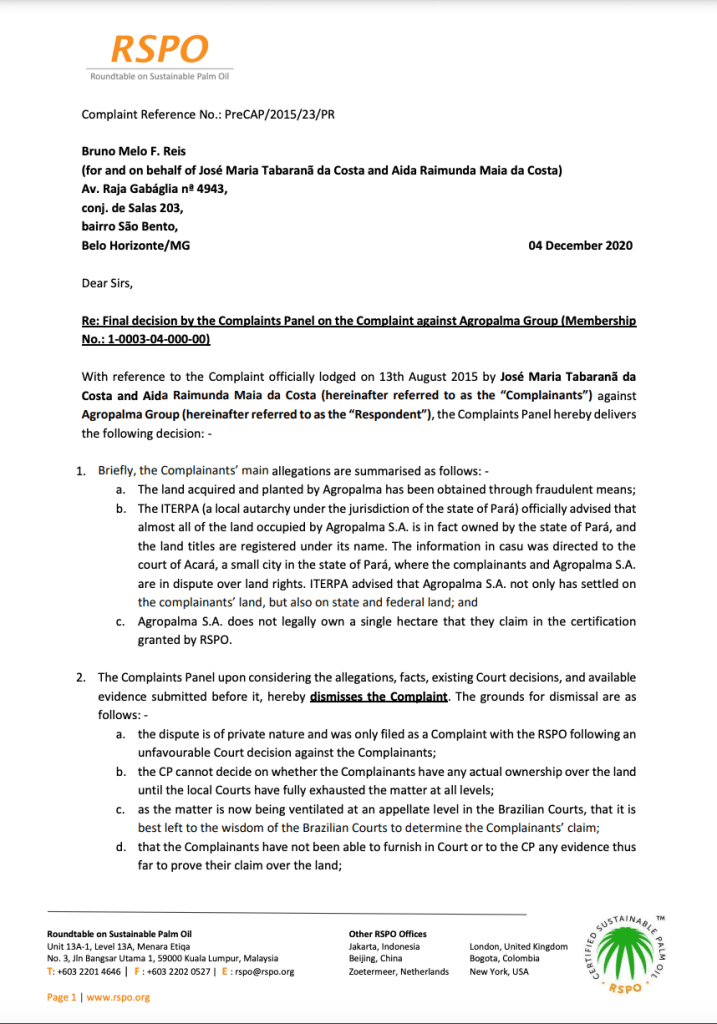

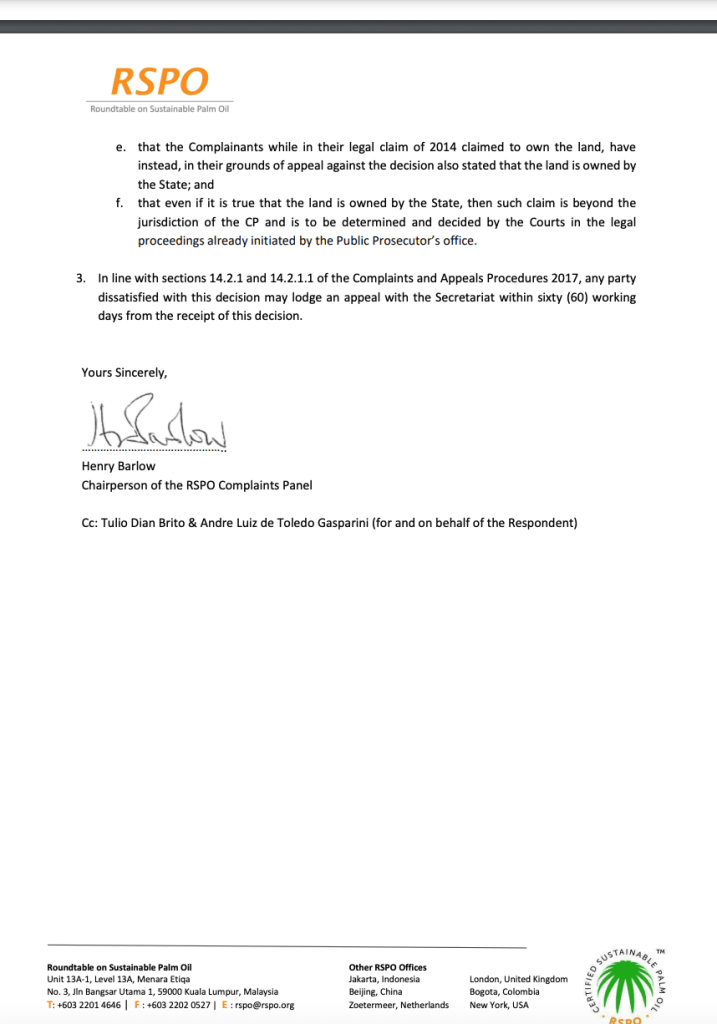

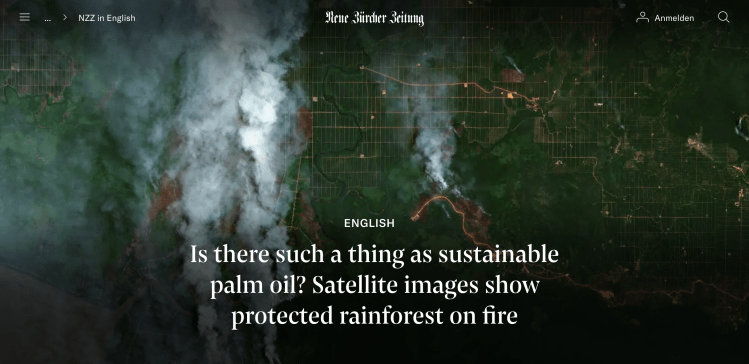

Thanks to the collective efforts of all those in the movement, the idea of “sustainable” palm oil is now well-known to be a greenwashing fabrication by the palm oil industry itself. No supply chain members of the industry certification the RSPO have actually ceased deforestation for palm oil. In 2024, the RSPO further diluted their definition of deforestation and weakened their standard further. Read in-depth about this in a ten part series on “sustainable” palm oil greenwashing.

Research Insight:

Consumers have a negative view of palm oil and see it as driven by greed, corruption, profit and capitalism. Social media campaigns against palm oil are successful

The expansion of oil palm plantations is under intense public scrutiny as it causes tropical deforestation and biodiversity loss in Southeast Asia. Little is known regarding the international public’s perceptions of palm oil’s impacts on environmental issues. This study used a large dataset of 4260 online posts gleaned from YouTube and Reddit. Our major findings are: (1) the public has negative views on palm oil. Several drivers of environmental destruction are greed, corruption, profit, and capitalism; (2) social media campaigns against palm oil are highly successful. However, negative sentiments from consumers reveal ongoing institutional failures; (3) public opinion is polarized in terms of viewpoints on socioeconomics and the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil; (4) global consumers’ response to boycott palm oil products and seek for other solutions are driven by corporations’ profit-driven malpractice and weak governmental legislation and governance.

This study is the first attempt to apply big data of social media accounts to analyze consumers’ perceptions of palm oil and its environmental impacts. It also proposes a predictive model for understanding factors and mechanisms of how social media applications can potentially stimulate and influence an international sustainability debate over palm oil.

Palm oil and its environmental impacts: A big data analytics study

Shasha Teng, Kok Wei Khong, Norbani Che Ha, Palm oil and its environmental impacts: A big data analytics study, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol 274, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122901.

Research Insight:

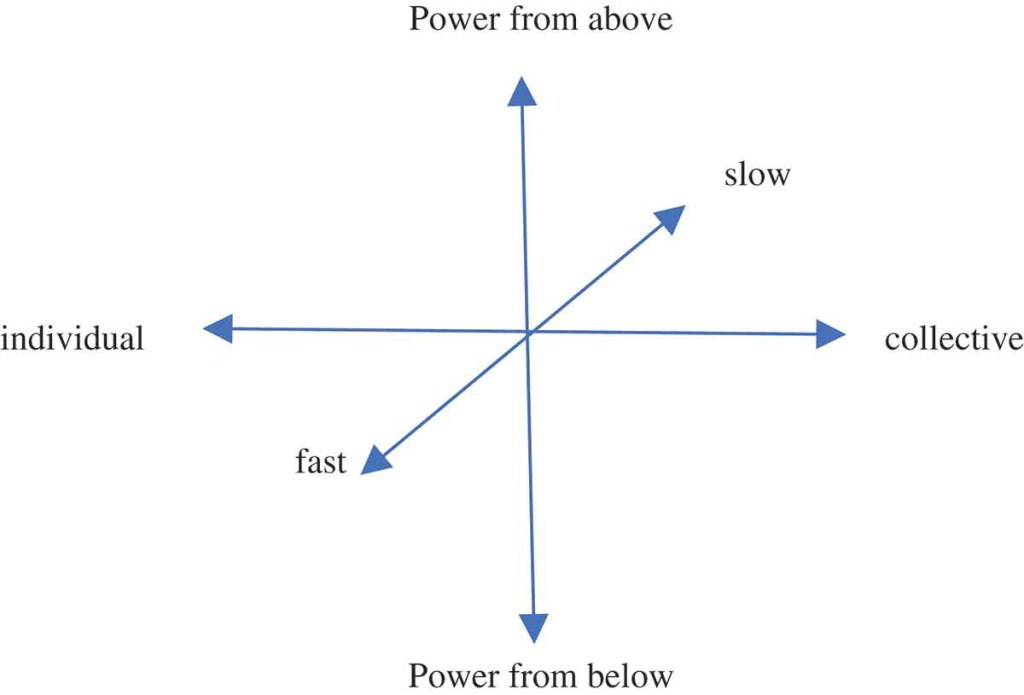

Power exercised from below based on dense social networks and drawing on legitimate cultural frames, can sustain actions, even in contact with powerful opponents

(Tarrow, 2011, p. 4). ‘When their actions are based on dense social networks and effective connective structures and draw on legitimate, action-oriented cultural frames, they can sustain actions even in contact with powerful opponents. in such cases – and only in such cases – we can speak of the presence of a social movement’ (Tarrow, 2011, p. 16). For the mobilization of individuals to contribute to collective action is largely based on shared beliefs and identification as well as social networks that foster connective structures and suggest suitable forms of political action.

Repression, resistance and lifestyle: charting (dis)connection and activism in times of accelerated capitalism (2020)

Anne Kaun & Emiliano Treré (2020) Repression, resistance and lifestyle: charting (dis)connection and activism in times of accelerated capitalism, Social Movement Studies, 19:5-6, 697-715, DOI: 10.1080/14742837.2018.1555752

Research Insight:

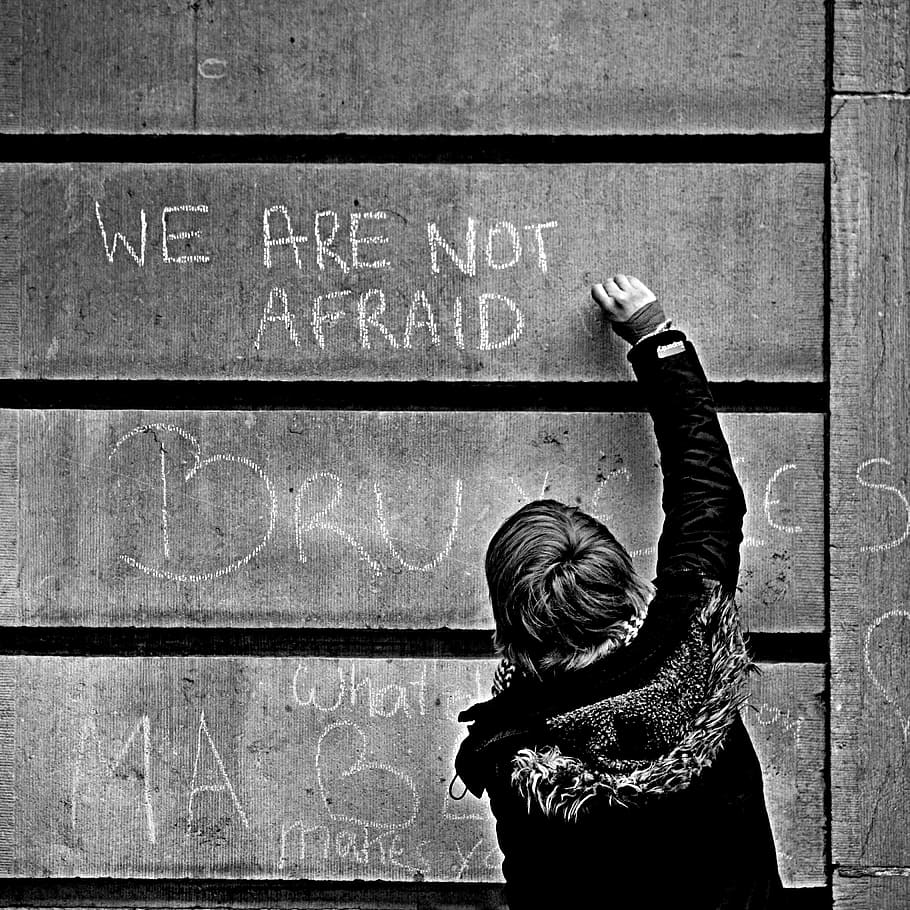

Hashtags and viral images are expressions of collective identity. Social media is a source of coherence and shared symbols, which people can turn to when looking for others in the movement

Hashtags and viral images are expressions of collective identification with political causes and organizations in the context of digital media. ‘Social media, as a language and a terrain of identification’, Gerbaudo argues, ‘becomes a source of coherence as shared symbols, a centripetal focus of attention, which participants can turn to when looking for other people in the movement’

Anne Kaun & Emiliano Treré (2020) Repression, resistance and lifestyle: charting (dis)connection and activism in times of accelerated capitalism, Social Movement Studies, 19:5-6, 697-715, DOI: 10.1080/14742837.2018.1555752

Anne Kaun & Emiliano Treré (2020) Repression, resistance and lifestyle: charting (dis)connection and activism in times of accelerated capitalism, Social Movement Studies, 19:5-6, 697-715, DOI: 10.1080/14742837.2018.1555752

Research Insight:

Large-scale individualised collective action is coordinated through digital technologies: Individuals are mobilised according to personal lifestyle issues, environmental protection, animal rights, workers rights and human rights

This article proposes a framework for understanding large-scale individualized collective action that is often coordinated through digital media technologies. Social fragmentation and the decline of group loyalties have given rise to an era of personalized politics in which individually expressive personal action frames displace collective action frames in many protest causes. This trend can be spotted in the rise of large-scale, rapidly forming political participation aimed at a variety of targets, ranging from parties and candidates, to corporations, brands, and transnational organizations. The group-based “identity politics” of the “new social movements” that arose after the 1960s still exist, but the recent period has seen more diverse mobilizations in which individuals are mobilized around personal lifestyle values to engage with multiple causes such as economic justice (fair trade, inequality, and development policies), environmental protection, and worker and human rights.

Bennett WL. The Personalization of Politics: Political Identity, Social Media, and Changing Patterns of Participation. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2012;644(1):20-39. doi:10.1177/0002716212451428

Research Insight:

Individuals who boycott value minimalism, individuals who ‘buycott’ value hedonism

Consumers boycott companies that they deem to be irresponsible or they may deliberately buy from companies that they perceive to act responsibly (‘buycott’). Using a unique, representative sample of 1833 German consumers, this study reveals that the effects of environmental concerns and universalism on buycotting are amplified by hedonism, while the effects of social concern on buycotting and boycotting are attenuated by hedonism and simplicity, respectively. These results have far-reaching implications for organizations and policy planners who aim to change corporate behavior.

Under Which Conditions Are Consumers Ready to Boycott or Buycott? The Roles of Hedonism and Simplicity

Stefan Hoffmann, Ingo Balderjahn, Barbara Seegebarth, Robert Mai, Mathias Peyer,

Under Which Conditions Are Consumers Ready to Boycott or Buycott? The Roles of Hedonism and Simplicity, Ecological Economics, Vol 147, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.01.004.

Research Insight:

Consumers pledge participation in boycotts for moral reasons and identify with the cause reflected by the boycott

Boycott pledgees explicitly express their desire for the target company to abolish its egregious behavior, their anger about the behavior in question, and their desire for punitive actions. Consumers pledge participation for moral reasons and identify with the cause reflected by the boycott. Boycott motivations also include the belief that consumers have the power to impact the boycott target’s bottom line and/or behavior as well as the belief that the boycott will succeed in forcing the target to cease its egregious behavior.

What motivates consumers to participate in boycotts: Lessons from the ongoing Canadian seafood boycott

Karin Braunsberger, Brian Buckler, What motivates consumers to participate in boycotts: Lessons from the ongoing Canadian seafood boycott, Journal of Business Research, Vol 64, Issue 1, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.12.008.

Research Insight:

Consumers avoid brands when the brand is incongruent with the individual’s identity, or when the consumers values, beliefs clash with the brand, or the brand has a negative impact on society

There are three types of brand avoidance: experiential, identity and moral brand avoidance. Experiential brand avoidance occurs because of negative first hand consumption experiences that lead to unmet expectations. Identity avoidance develops when the brand image is symbolically incongruent with the individual’s identity. Moral avoidance arises when the consumer’s ideological beliefs clash with certain brand values or associations, particularly when the consumer is concerned about the negative impact of a brand on society.

Anti-consumption and brand avoidance

Michael S.W. Lee, Judith Motion, Denise Conroy, Anti-consumption and brand avoidance, Journal of Business Research, Vol 62, 2009, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.01.024.

Research Insight:

Brand hate is linked to negative word-of-mouth, online and offline complaining and non-repurchase intention

Findings reveal that brand hate causes offline negative word-of-mouth, online complaining, and non-repurchase intention. A mediated path was identified, which starts from brand hate and ends with non-repurchase intention through online complaining and offline negative word-of-mouth.

Brand hate and non-repurchase intention: A service context perspective in a cross-channel setting,

Ilaria Curina, Barbara Francioni, Sabrina M. Hegner, Marco Cioppi, Brand hate and non-repurchase intention: A service context perspective in a cross-channel setting, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, Vol 54, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.102031.

Insight:

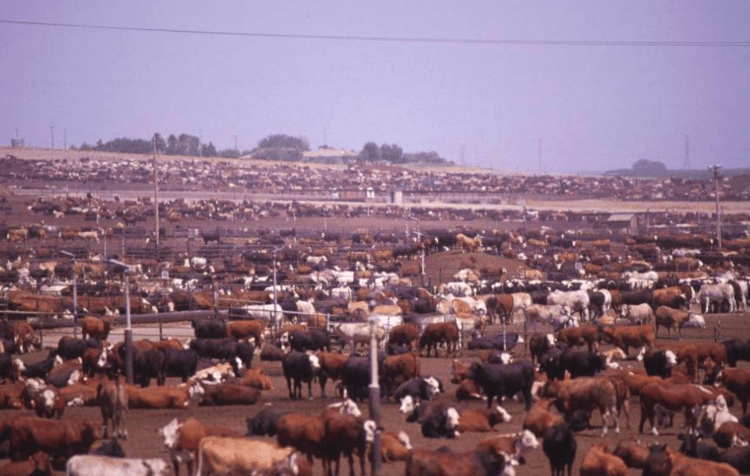

Boycotts hit corporations where it hurts – their reputation and market share. Globally, some of the most impressive environmental achievements have come via boycotts.

~ Prof Bill Laurance, James Cook University.

Campaigns and boycotts get the attention of these large corporations, because they hit them where it hurts: their reputation and market share.

Globally, some of the most impressive environmental achievements have come via boycotts, or at least the threat of them.

Across the globe, boycotts have helped to rein in predatory behaviour by timber, oil palm, soy, seafood and other corporations.

Professor Bill Laurance, James Cook University, ‘Boycotts are a crucial weapon to fight environment-harming firms’,The Conversation (2014).

Further reading

(2017) A Deluge of Double-Speak. Jason Bagley. Truth in Advertising. https://www.truthinadvertising.org/a-deluge-of-doublespeak/

(2020) Balanced Growth. In: Leal Filho W., Azul A.M., Brandli L., özuyar P.G., Wall T. (eds) Responsible Consumption and Production. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95726-5_300007

Client Earth: The Greenwashing Files: https://www.clientearth.org/the-greenwashing-files

(2021) Earth Day 2021: Companies Accused of Greenwashing. Truth in Advertising. https://www.truthinadvertising.org/six-companies-accused-greenwashing/

Effect of oil palm sustainability certification on deforestation and fire in Indonesia, Kimberly M. Carlson, Robert Heilmayr, Holly K. Gibbs, Praveen Noojipady et al. PNAS January 2, 2018 115 (1) 121-126 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1704728114

(2019) Fifteen environmental NGOs demand that sustainable palm oil watchdog does its job. Media release. Rainforest Action Network. https://www.ran.org/press-releases/fifteen-environmental-ngos-demand-that-sustainable-palm-oil-watchdog-does-its-job/

(2011) Greenwash and spin: palm oil lobby targets its critics, Alex Helan. Ecologist: Informed by Nature. https://theecologist.org/2011/jul/08/greenwash-and-spin-palm-oil-lobby-targets-its-critics

(2011) Green marketing and the Australian Consumer Law. Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. https://www.accc.gov.au/publications/green-marketing-and-the-australian-consumer-law

Greenwashing: definition and examples, Selectra: https://climate.selectra.com/en/environment/greenwashing

(2011) Greenwashing: The Darker Side Of CSR. Priyanka Aggarwal, Shri Ram College of Commerce (University of Delhi). Indian Journal of Applied Research 4(3):61-66 DOI:10.15373/2249555X/MAR2014/20 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275755662_Greenwashing_The_Darker_Side_Of_CSr

(2021) Green Clean. Cathy Armour (Commissioner, Australian Securities & Investments Commission). Company Director Magazine. https://aicd.companydirectors.com.au/membership/company-director-magazine/2021-back-editions/july/the-regulator

(2015) Group Challenges Rainforest Alliance Earth-Friendly Seal of Approval. Truth in Advertising. https://www.truthinadvertising.org/group-challenges-rainforest-alliance-eco-friendly-seal-of-approval/

(2021) How Cause-washing Deceives Consumers. Truth in Advertising https://www.truthinadvertising.org/how-causewashing-deceives-consumers/

(2019) Kellogg on Branding in a Hyper-Connected World Alice M. Tybout (Editor-in-Chief), Tim Calkins (Editor-in-Chief), Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University. https://www.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-111953318X,descCd-buy.html

(2020) No such thing as ‘sustainable’ palm oil, says Indonesian youth activist. Michael Taylor. Thomson Reuters Foundation. https://www.reuters.com/article/indonesia-climate-activist-trfn-idUSKBN28I2MP

(2018) No such thing as sustainable palm oil – ‘certified’ can destroy even more wildlife, say scientists. Jane Dalton. The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/climate-change/news/palm-oil-sustainable-certified-plantations-orangutans-indonesia-southeast-asia-greenwashing-purdue-a8674681.html

(2019) Palm oil watchdog’s sustainability guarantee is still a destructive con. Environmental Investigation Agency. https://eia-international.org/news/palm-oil-watchdogs-sustainability-guarantee-is-still-a-destructive-con/

(2020) Quorn advert that claimed its food could ‘help reduce carbon footprint’ ruled misleading. Sophie Gallagher. The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/food-and-drink/quorn-advert-claimed-its-food-could-reduce-consumer-s-carbon-footprint-ruled-misleading-b696403.html

(2019) Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil is ‘greenwashing’ labelled products, environmental investigation agency says. Annette Gartland. Changing Times Media. https://changingtimes.media/2019/11/03/roundtable-on-sustainable-palm-oil-is-greenwashing-labelled-products-environmental-protection-agency-says/

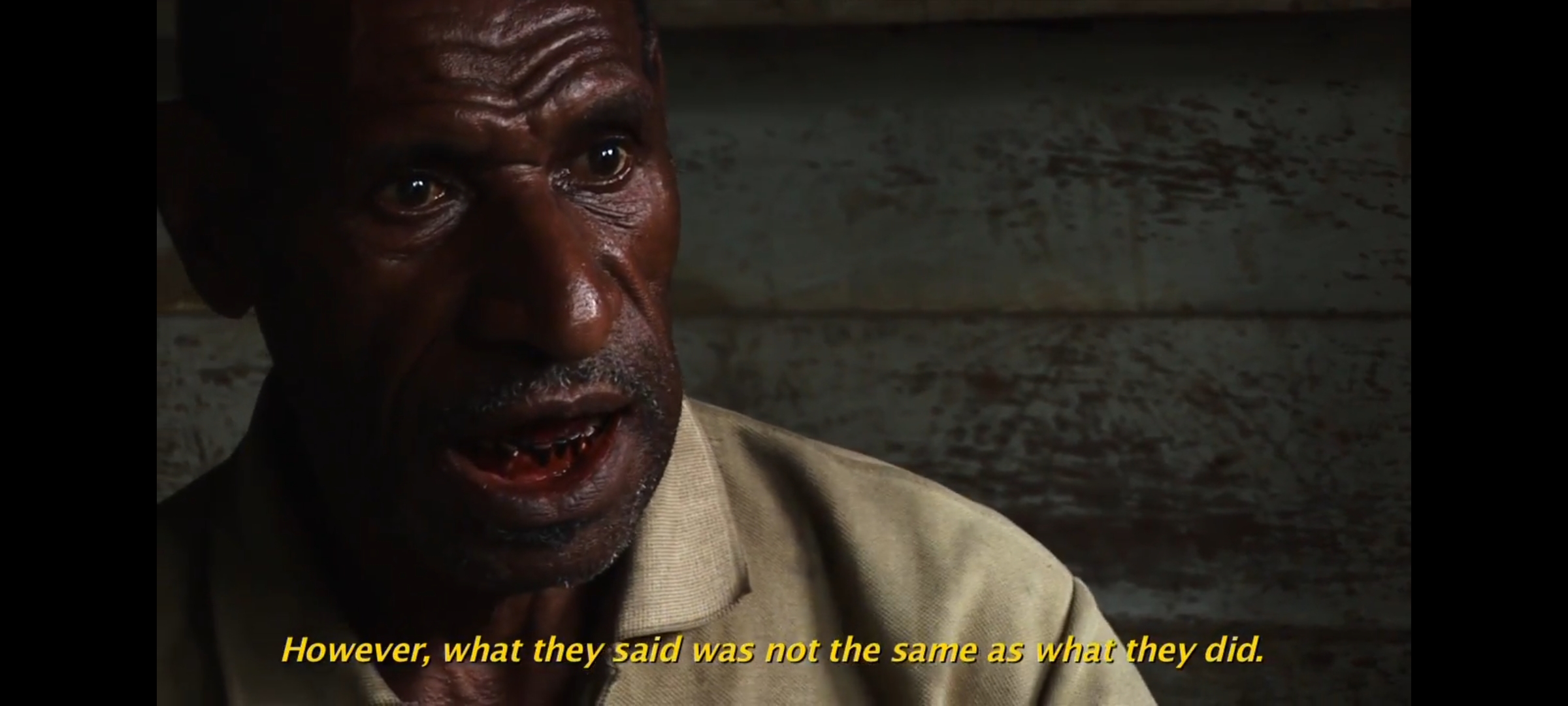

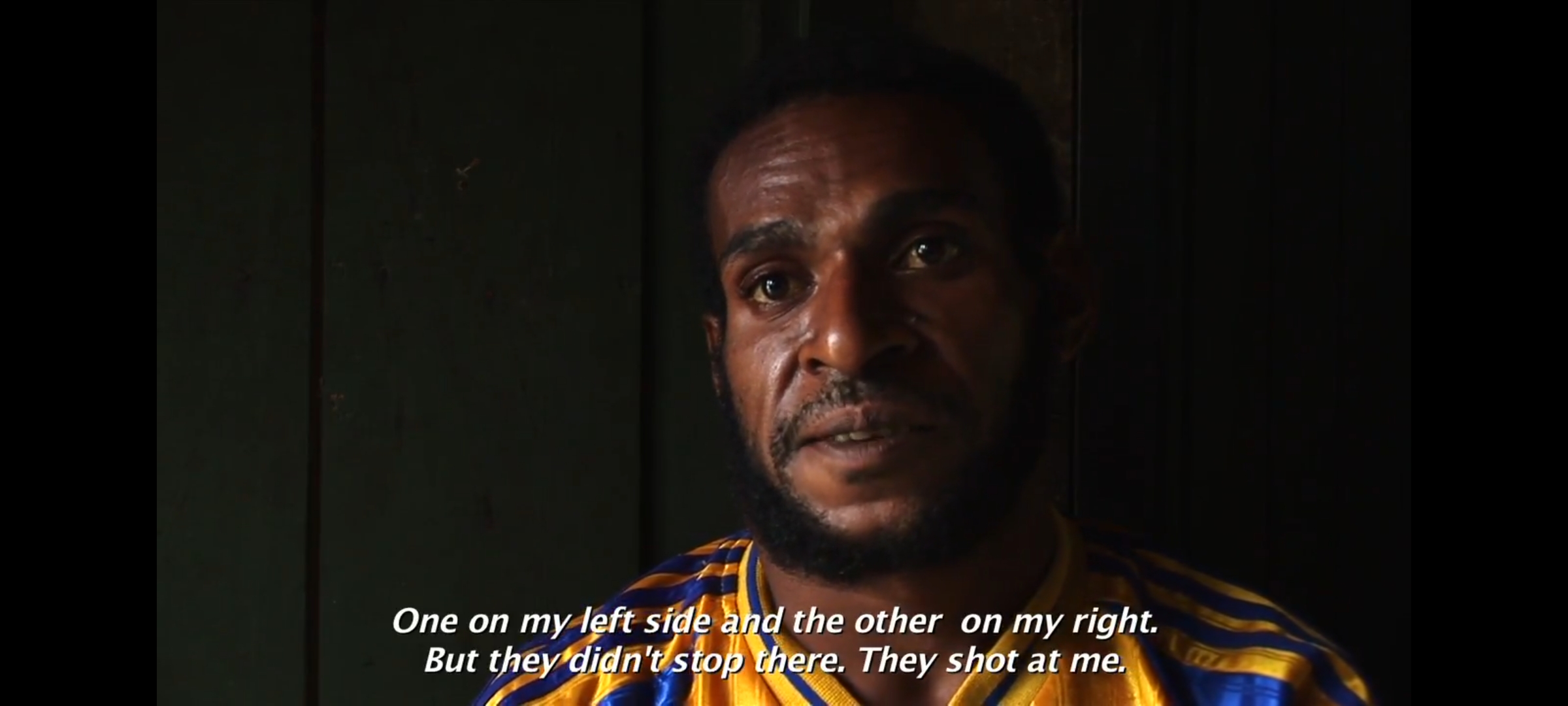

(2018) RSPO: 14 years of failure to eliminate violence and destruction from the industrial palm oil sector. Friends of the Earth International. https://www.foei.org/news/rspo-violence-destruction

(2019) Study in WHO journal likens palm oil lobbying to tobacco and alcohol industries. Tom Miles. Reuters https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-palmoil-idUSKCN1P21ZT

The palm oil industry and noncommunicable diseases. Sowmya Kadandale,a Robert Martenb & Richard Smith. World Health Organisation Bulletin 2019;97:118–128| doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.18.220434

(2018) Roberto Cazzolla Gatti, Jingjing Liang, Alena Velichevskaya, Mo Zhou, Sustainable palm oil may not be so sustainable, Science of The Total Environment, Volume 652, 2019, Pages 48-51, ISSN 0048-9697, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.222.

Truth in Advertising: Green Guides and Environmentally Friendly Products. Federal Trade Commission: Protecting America’s Consumers. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/media-resources/truth-advertising/green-guides

(2021) The Time Has Come to Rein In the Global Scourge of Palm Oil. Jocelyn Zuckerman. Yale Environment 360, Yale School of Environment. https://e360.yale.edu/features/the-time-has-come-to-rein-in-the-global-scourge-of-palm-oil

(2021) What is Greenwashing and How to Tell Which Companies are Truly Environmentally Responsible, Hewlett Packard, July 2021 https://www.hp.com/us-en/shop/tech-takes/what-is-greenwashing-environmentally-responsible-companies

(2021) ‘What do Millennials think of palm oil? Nestlé investigates’ Flora Southey. Food Navigator. https://www.foodnavigator.com/Article/2021/08/12/What-do-Millennials-think-of-palm-oil-Nestle-investigates